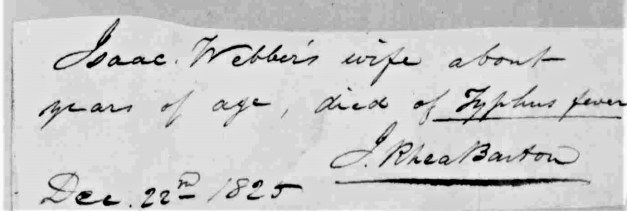

15 October 1828: “Bethel Church Minute & Trial Book”

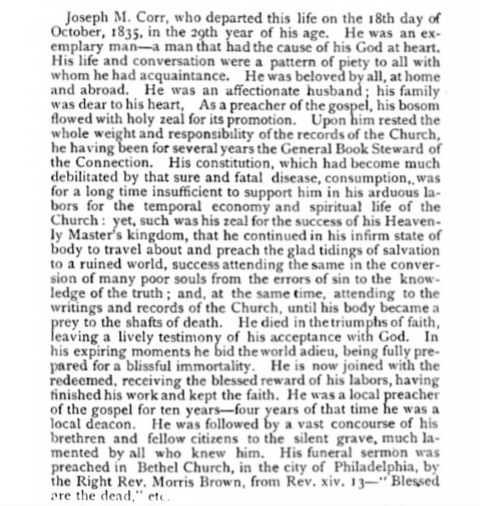

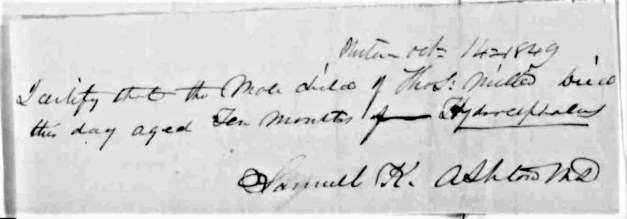

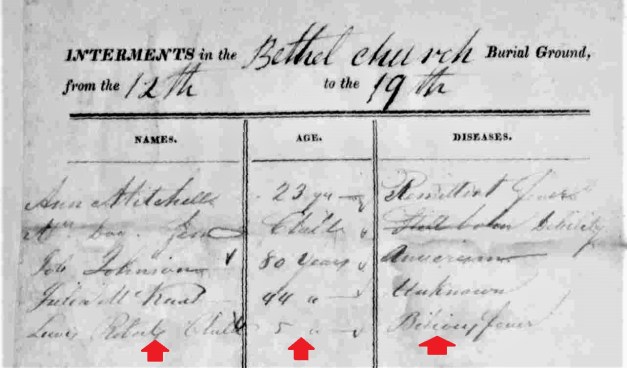

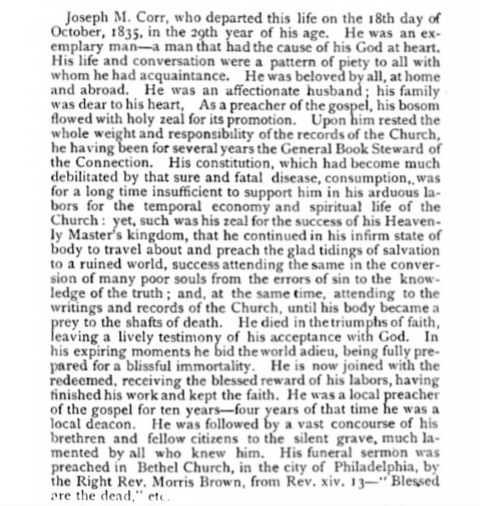

Twenty-eight-year-old Rev. Joseph Corr died this date, October 18th, in 1835 of Tuberculosis and I assume that he was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. The death certificate no longer exists for Rev. Corr. However, he was a preacher and class leader at Bethel AME Church and also served as the Church’s Secretary. Given the year he died, his involvement with the Church and the personal relationship he enjoyed with Bishops Richard Allen and Morris Brown, I believe it is safe to assume that Rev. Corr was interred in Bethel Burying Ground. The information we have on Rev. Corr comes from historical African Methodist Episcopal Church documents and newspapers of the era.

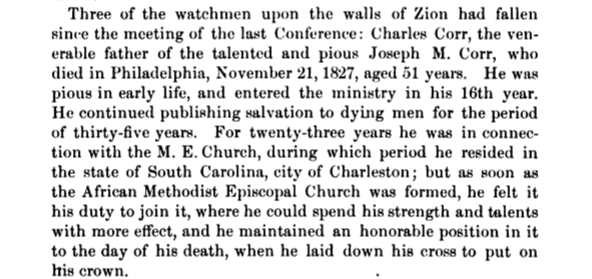

“A WATCHMAN OF ZION DIES”

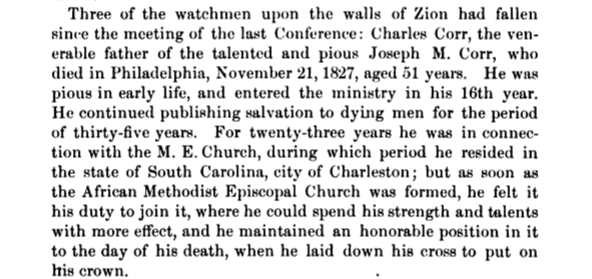

Rev. Joseph Corr’s father, Charles, was also a well respected AME minister.

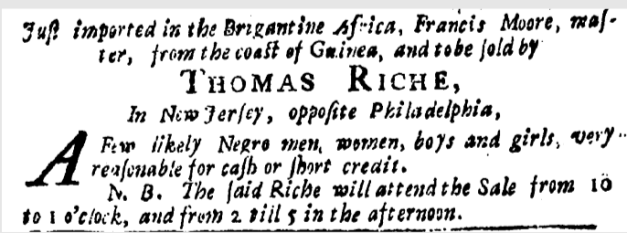

Rev. Charles Corr was among those that fled Charleston, South Carolina to Philadelphia after the enslaved Denmark Vesey plotted a revolt in 1822. The uprising failed and the petrified white leadership of the city saw the local Black clergy as potential rebellion leaders and ordered them to leave the state under penalty of death. Joseph M. Corr would have been fifteen or sixteen years old when he fled north with his family to Philadelphia and the relative safety of Bishop Allen’s Bethel Church. (1)

“MOST GIFTED PREACHER”

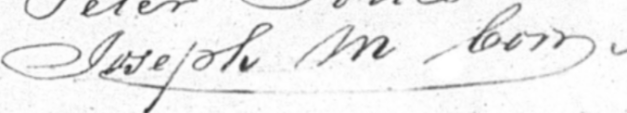

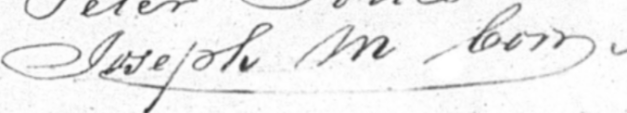

Joseph M. Corr was sixteen-years-old when he started preaching at Bethel Church. He soon was hailed by the senior leadership as the “most gifted preacher.” He was the youngest member in the Church’s Conference which included Philadelphia, New York City, and Baltimore. Bishop Richard Allen chose the young man (“the best-educated”) to be the Secretary for the whole Conference and also Secretary specifically for Bethel Church. (2)

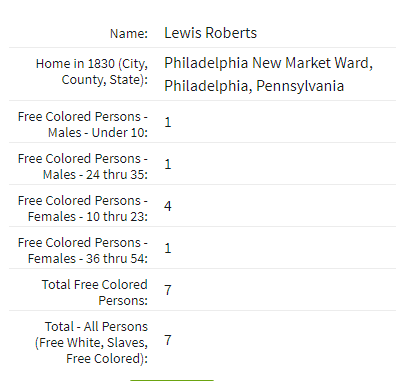

The young man supplemented his church income by working as a tailor. (3) He eventually would marry a woman named Emeline and start a family. Ms. Corr was employed as a laundress. (4)

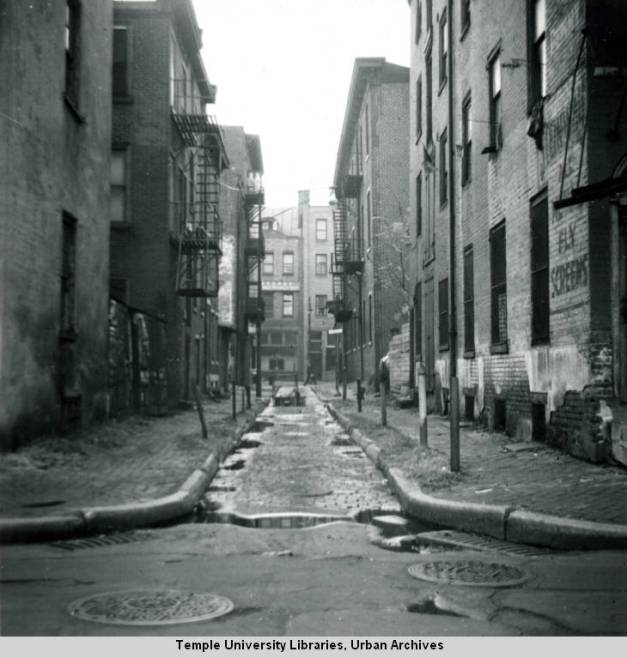

“WRETCHED SPOT”

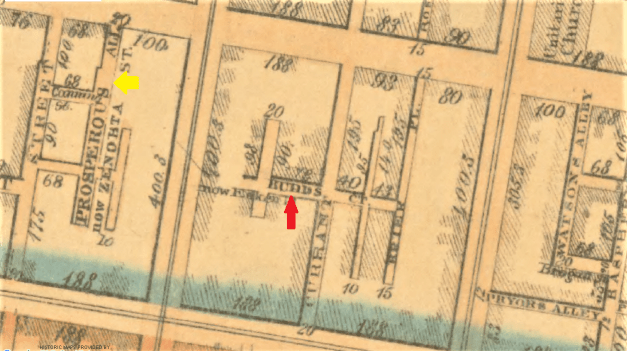

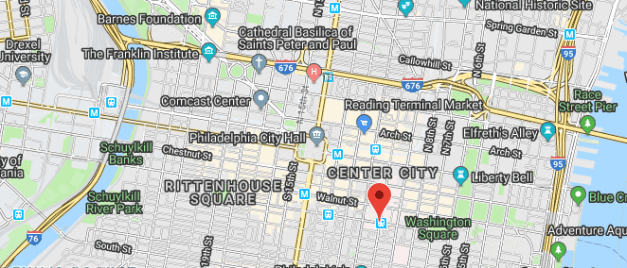

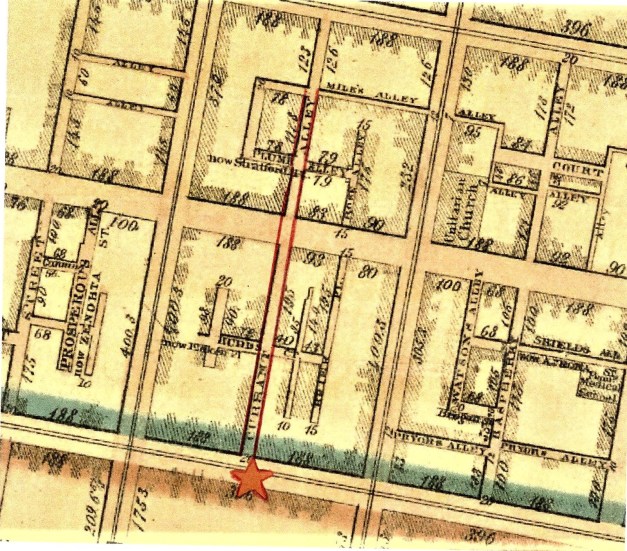

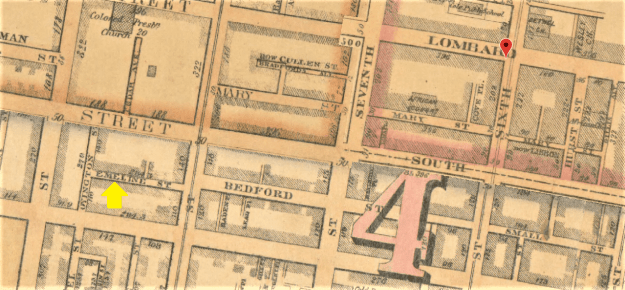

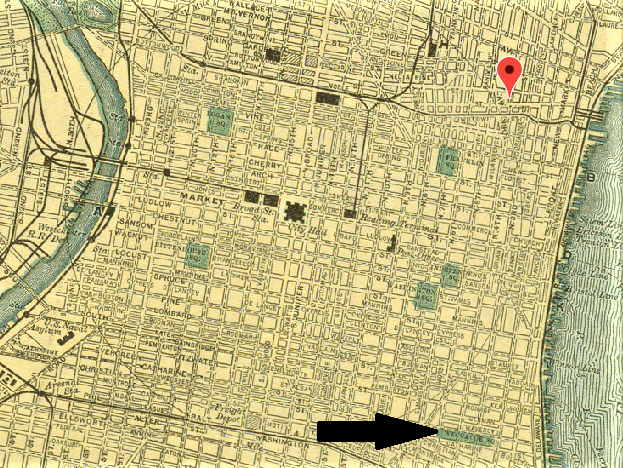

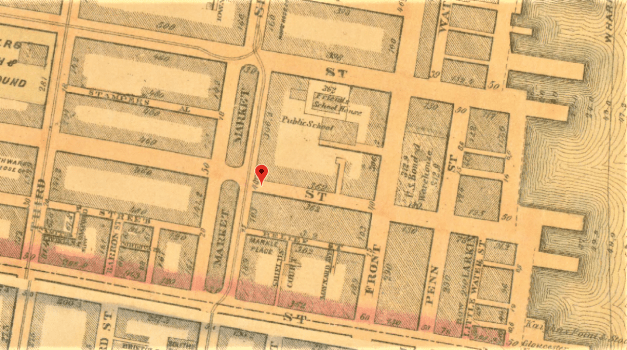

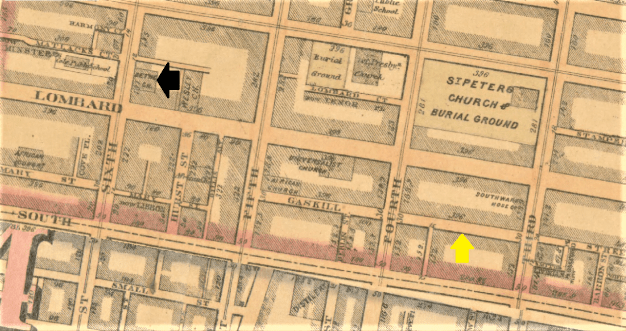

There were many streets, courts, and alleys in Philadelphia where living conditions were so bad that words almost fail to describe the human misery that existed therein. Small Street was one of those places. Reverend Corr chose to live on Small Street. He and his spouse both worked at occupations that would allow them to live somewhere better than Small Street. Two and one-half years after Rev. Corr’s death, Ms. Corr reported her personal wealth of $600 or $16,200 in present-day currency.

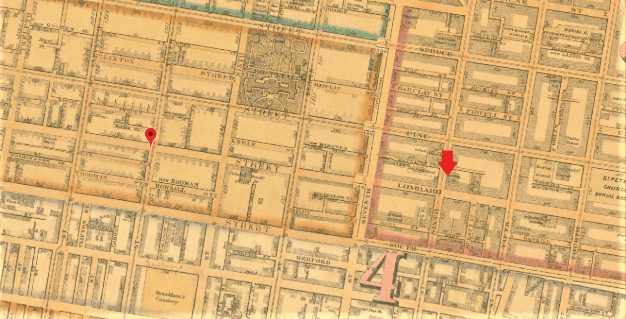

Small Street’s location is indicated by the red oval. The black diamond illustrates the location of the “Commons.” (See quote below.)

The skeletons of many horses lay bleaching in the sun, while lame horses were limping about, and others which but lately died were half devoured by dogs and crows. . . . it was on this common that long rows of sheds, weatherboarded, partitioned, and with a door to each compartment, were erected to accommodate the miserable inmates of Small street and St. Mary street with healthy summer residences during the great cholera season of 1832. Small street and St. Mary street were cleaned out, and fences were put across to prevent persons from going into them. . . . men, women, and children, black and white, barefooted, lame, and blind, half-naked and dirty, carrying old stools, broken chairs, thin-legged tables, and bundles of beds and bed clothing to their summer retreat on the common! (5) (Note: A “common” is open land belonging to the community.)

⊕⊕⊕⊕⊕⊕⊕⊕

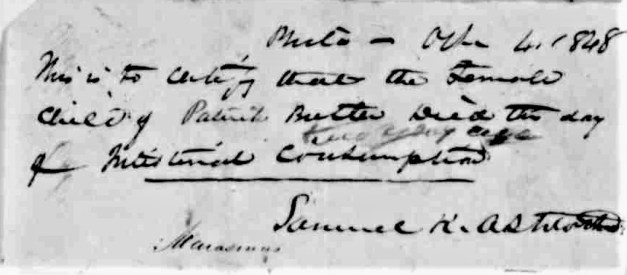

3 July 1834: “Bethel Church Minute& Trial Book.”

The city and surrounding districts suffered epidemic-after-epidemic of Cholera in the 1830s. No one in the medical community knew how infectious diseases were spread. We now know the cause of the disease was drinking water fouled with human feces. However, most of the population believed the cause of the disease was miasma or poisonous vapors. White racists believed African Americans naturally gave off these vapors, especially in overcrowded neighborhoods. The editor of the most popular newspaper in Philadelphia called Small Street “a wretched place” and a “crowded sink [cesspool] of filth.” He went even further to warn white city leaders that Small Street likely would be the epicenter of a plague on the scale that destroyed London in 1666. He was raising the fear of the Black Death caused by the African Americans on Small Street. The home of Rev. Corr and his family.

“TO SMALL STREET TO SMALL STREET!!”

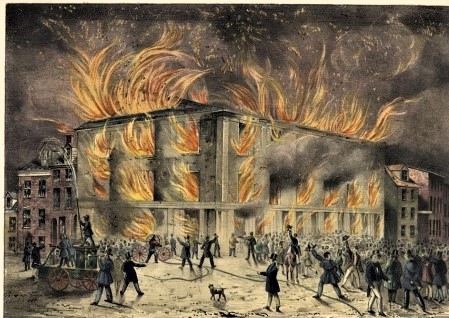

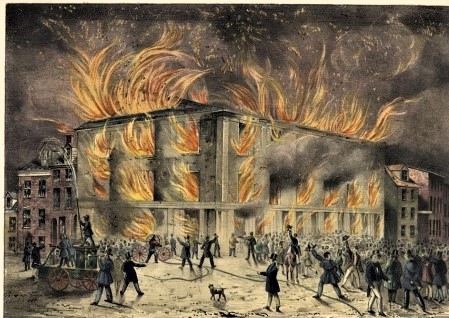

After the demonization of Small Street as the devil’s den, it is no surprise what happened next. On the second night of the “Flying Horse” rioting in July of 1834, the frenzied white mob of thousands turned its attention to the homes of Rev. Corr and his neighbors, chanting “To Small Street, To Small Street” as they advanced.

The mob tore into the homes pillaging, breaking windows and destroying everything in the tenements including furniture and bedding. Most of the residents already had fled, probably into the adjoining fields and marshes of Moyamensing. Those that remained were severely beaten and an unknown number killed and their bodies mutilated. At one point, the mob captured a Black man and surrounded him, chanting “Kill him – beat him – place him under the pump.” The last call was for the water torturing of a human being.

⊕⊕⊕⊕⊕⊕⊕

” . . another gap was made in the ranks of the early pioneers.”

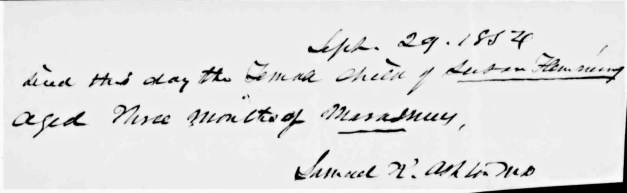

5 August 1835 “Bethel Church Minute & Trial Book.” This was two months before his death.

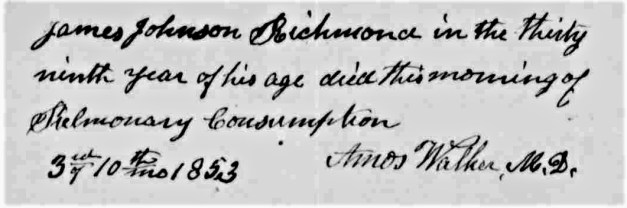

We know that the Corr family survived the invasion and assault. We don’t know what they came back to at #75 Small Street. Sadly, Rev. Corr would succumb to Tuberculosis fourteen months later on October 18th in 1835. He was only twenty-eight-years-old.

Rev. Corr’s funeral service was preached in Bethel Church by Bishop Morris Brown. He quoted from Revelations 14-13:

“And I heard a voice from heaven saying unto me, Write, Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord from henceforth: Yea, saith the Spirit, that they may rest from their labours; and their works do follow them.” (7)

“EMELINE CORR”

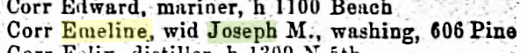

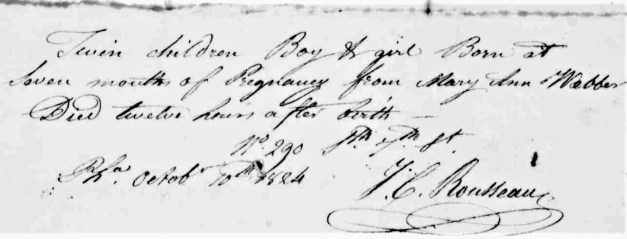

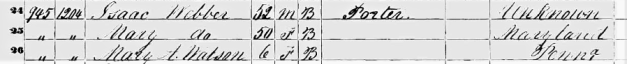

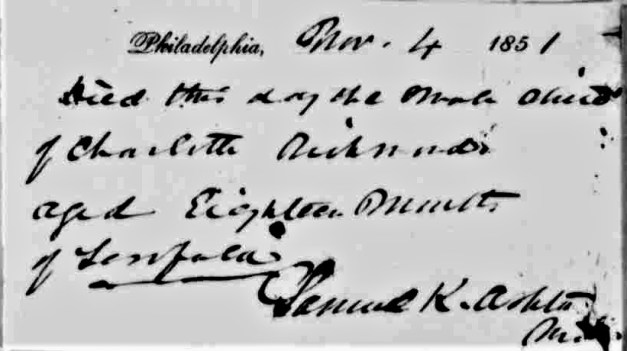

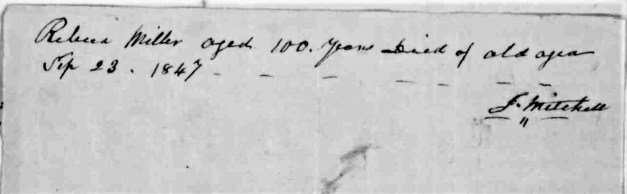

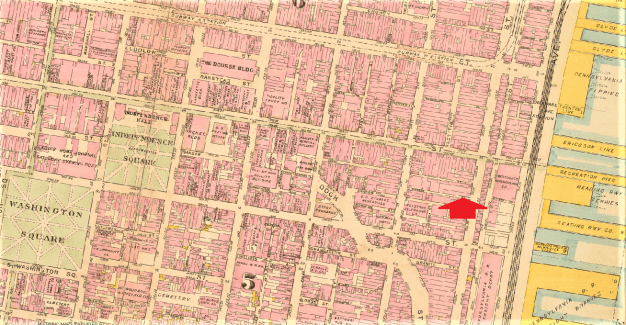

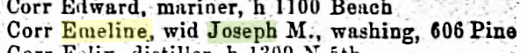

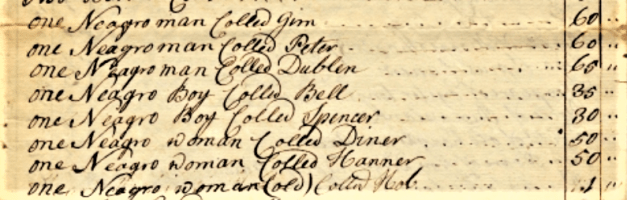

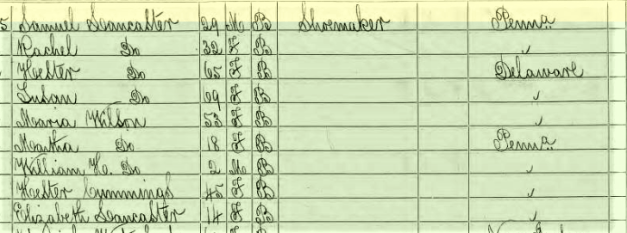

Shortly after burying her husband at Bethel Burying Ground, Ms. Corr moved to the 600 block of South Street on the southern border of the city, according to the 1838 Philadelphia African American Census. It appears that Joseph Corr left four children fatherless, three of whom were attending school in 1838. The Census also reveals that Ms. Corr formerly had been enslaved and gained her freedom for $100. All the children were born in Pennsylvania.

The 1838 census reported that Ms. Corr was a “dealer.” In my experience, this usually means a baker or a dealer in cakes, pies or confectionary when it refers to a woman. On occasion, it also has meant a proprietor of a used clothing store. Whatever she was “dealing,” it appears that Ms. Corr was very successful. As mentioned above, she reported her personal wealth in 1838 at $600 or $16,200 in present-day currency. A small fortune for a single Black woman during this time.

The last mention in the public record of Ms. Corr that I can locate is in the 1870 Philadelphia City Directory.

wid = widow

REFERENCES

(1) “History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church” by Daniel A. Payne, p. 59.

(2) Ibid., 43.

(3) Ibid., v.

(4) 1870 Philadelphia City Directory.

(5) Annals of Philadelphia, and Pennsylvania in the olden time; being a collection of memoirs, anecdotes, and incidents of the city and its inhabitants, and of the earliest settlements of the inland part of Pennsylvania by John F. Watson, v.3, p 3.

(5) Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser, 22 August 1832.

(6) Daily Pennsylvanian, 15 August 1834.

(7) An outline of our history and government for African Methodist Churchmen, ministerial, and lay: in catechetical form: two parts by Rev. Benjamin T. Tanner, p. 159. Below is Rev. Tanner’s full entry on Rev. Cox.

![]()