Introduction

Ignatius Beck was a common man forced by prejudiced state of affairs to uncommon levels of accomplishment and action. He was a person of courage, integrity and sound judgment, who was proclaimed “respectable in his appearance and demeanor, and unimpeached by a whisper against his veracity or general character.”[1] Acknowledged respectfully in his later years by the African American community as “Uncle Beck,” he was a dedicated family man and an early member of Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church. Beck was a trusted[2] associate of its founder, Reverend Richard Allen,[3] who appointed him a “Class Leader.”[4] In addition, Beck was the first chairman (1830) of the Free Produce Society of Philadelphia. The Society advocated for the purchase of food and textiles only raised by the labor of freemen and to boycott those items that were raised by the labors of enslaved men and women.[5]

Enslaved Capitol Builder

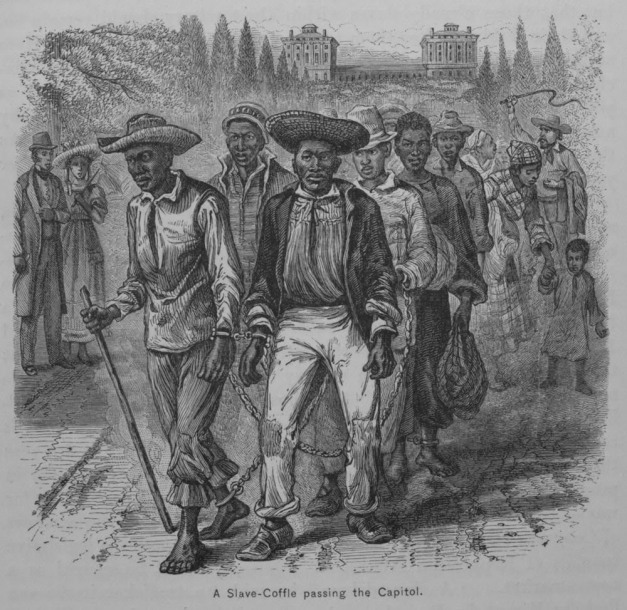

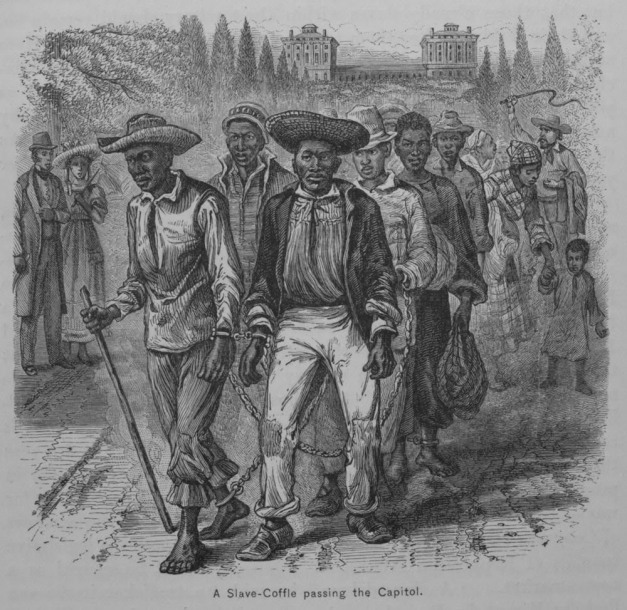

Mr. Beck was born to an enslaved mother on Joseph Beck’s tobacco plantation in either 1774 or 1775. The plantation was on the outskirts of what is now Bowie, Maryland. In 1791, at the age of sixteen he was legally guaranteed manumission at his 25th birthday. However, when he was nineteen years old he was “rented” out as a laborer to the contractor that was building the United States Capitol Building in the nearby District of Columbia. Federal archival records show payments for “Negro hire” to assist in the construction of the United States Capitol Building beginning on February 11, 1795 and ending on May 17, 1801. In total there were 385 payments made out during that period. Initially, the contracted annual rate for slaves was $60 which all went to the slave’s owner. The owner’s only obligations were to provide a set of adequate clothes and a blanket which offered little protection against the deadly mosquitoes in summer and the bitter cold in winter. Beck’s duties could have included timber and stone sawing, brick making, bricklaying and the strenuous hauling that comes from these tasks.[6]

Blackball maker

After 25 years of being enslaved Ignatious was freed in in either 1800 or 1801 and made his way north to Philadelphia. One of the decisions that a newly freed slave makes is choosing a last name. He chose the name of his former master.

Initially, the Beck family lived at an unknown address on south 7th Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In 1810 they moved to 14 St. Mary’s Street (now Rodman Street), which runs between 6th and 8th Streets and Lombard and Pine Streets. The tenement was located on what is now Starr Gardens Playground and within sight of Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church. Mr. Beck worked out of his home making blackball. Beeswax, lampblack and animal fat were mixed in combination to make a substance that was rolled into one-ounce balls. The predecessor to shoe polish, this “blackball” was used to blacken and preserve shoes, boots and military leather equipment. With the invention of shoe polish in 1800 the use of blackball was only used by certain segment of the military. Each maker of blackball had their own formula and Beck’s must have been was very popular because the city directories have him manufacturing it out of his home until at least 1814; fourteen years after shoe polish became available.[7]

Kidnapped

Residing on St. Mary’s Street in 1810 and struggling with the cost of raising a family, Beck cast his fate to the wind. He was approached by a seemingly respectable and well to do white man with an offer of employment. Beck was to accompany him as his man servant to North Carolina for a period of time and for this service he would be well paid. Financial circumstances dictating the decision and he agreed to the terms. The arrangement was going well as the two men approached an inn on a Saturday evening just on the North Carolina side of the border from Virginia. The next morning, the Sabbath, the white man suggested that Beck might want to accompany a local group of slaves owned by the inn keeper to a Baptist meeting seven miles down the road from the inn. Disposed to do so, he made the journey and returned to the inn that evening only to find his employer had departed. Bewildered, Beck asked the inn keeper how he was to get back home to Philadelphia. The malefactor replied that he was “home” and that he now belonged to him as he bought the duped Black man from “his master.”

Now a prisoner in a hostile land the “shrewd and sensible man” did not rebel or fight back against his kidnapper. Temporarily accepting his position he went about convincing the whites around him that he was not a threat to escape or seek revenge. Gently, Beck went about inquiring if there was a white man in the area who might be sympathetic to his plight. He was told to seek out a local man, a justice of the peace, who “appeared quite friendly.” At great risk he introduced himself to this individual who listened to the history of the case and with “great joy” heard the compassionate man state that “he was willing to render all the assistance in his power.”

The sympathetic magistrate asked Beck what evidence he might have to prove his claim. Ignatius stated that the Reverend Richard Allen, pastor of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, would be able to substantiate his claims. The magistrate wrote Allen and told Beck to go back to the inn while they waited for a reply. However, the slave master caught wind of the plot and Ignatius fled to the magistrate’s home where he was kept in the cellar for hiding as slave catchers and night riders roamed the country side attempting to collect the bounty on the fugitive’s head. In the intervening time, Reverend Allen received the request and solicited the assistance of Isaac Hopper, an uncompromising Quaker abolitionist and activist who was known as the “Father of the Underground Railroad.” Allen and Hopper put together the necessary letters and official documents proving that Ignatius was indeed a freeman and a person of “unimpeachable general character.”

The brave magistrate received the documents, but fearing that Beck would not receive justice from the local vigilantes he hatched a plan. The magistrate had his son escort the escapee on a dangerous journey north for 100 miles while dodging the local slave catchers and their bloodhounds. Successful in their mission, Beck was given forged papers by the young, white Virginian “to prosecute the remainder of his journey.” Beck completed his journey home without reported further incident. After several weeks home he saw his kidnapper on the streets of Philadelphia and followed him to a residence on Lombard Street. Isaac Hopper, a Quaker abolitionist, procured a warrant for the kidnapper’s arrest. Hopper accompanied the constable to the Lombard Street residence, but the offender had fled and was never heard of again by Beck or the local abolitionists.[8]

Soldier in the War of 1812

Martin R. Delany (1812-85) was a historian, journalist, abolitionist, Harvard graduate, physician, and judge. He was the first African American commissioned a major in the Army and widely considered America’s first African American Nationalist, the forerunner of Marcus Garvey, Paul Robeson, and Malcolm X. In his role as historian he wrote and published “one of the most important books to be written by a free African American in the nineteenth century.”[9] In his seminal work, “The Condition, Elevation, Emigration and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States,”[10] Delany writes of the response and participation of Philadelphia African Americans to the call to arms (picks and shovels actually) by the Reverends Richard Allen and Absalom Jones. With the looming threat of invasion by the British on Philadelphia, the Engineer Corps of the U.S. Army requested assistance from the citizens of Philadelphia in erecting ramparts or breastwork on the west side of the Schuylkill near Gray’s Ferry. The African American community’s response was robust. Primary sources (government documents) do not exist for an official register or list of names for the company of men that responded. Estimates of their numbers range from 1,000 to 2,500. However, Delaney reports from Federal court documents and possibly from oral histories, that Ignatius Beck was one of the “Black Warriors” or “Black Pioneers” of 1812. He would have been approximately 38 years of age.

Underground Railroad Pioneer

In 1847, the African American owned and edited abolitionist newspaper, The Ram’s Horn acknowledged and praised Beck as being a co-founder of the Underground Railroad and in the vanguard of establishing the fugitive slave network as a working system of stations, stations masters, cars and coaches. An “estimable” man worthy of respect and honor, the newspaper went on to write about Beck that he was one of a very few in the early years of the Underground Railroad to be a vigilant manager of the network and a keystone in its success.[11]

Religious Man

Ignatious was an early member of Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Beck was a trusted[12] associate of its founder, Reverend Richard Allen,[13] who appointed him a “Class Leader.” In this position he acted as a “proxy pastor” and someone who heads a small group of congregants and looks after their spiritual and secular needs.”[14] Additionally, he was Mother Bethel’s sexton for several years. In this capacity he was responsible for the burials at Bethel Burying Ground.[15]

Community Organizer

Mr. Beck was the first chairman (1830) of the Free Produce Society of Philadelphia. The Society advocated for the purchase of food and textiles only raised by the labor of freemen and to boycott those items that were raised by the labors of enslaved men and women.[16]

The Stansbury Case

In January of 1839, William Stansbury, a free black man, was “seized in the streets of Philadelphia” by the notorious slave catcher George F. Alberti and accused of being a fugitive slave. The allegation was that he escaping from his enslavement in Prince George’s County, Maryland twenty-three years earlier. Mr. Stansbury’s case was quickly taken up by The Pennsylvania Abolition Society and two highly experienced attorneys, Charles Gilpin and David Paul Brown, were charged with defending Mr. Stansbury.

In a landmark case tried before Judge Joseph Hopkinson of the United States District Court for Eastern Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Ignatius Beck was the key witness for the defense. The two month long trial began on January 31, 1839 and ending in March of the same year. Judge Hopkinson decided that William Stansbury was a freeman and not a fugitive slave. In his ruling, Hopkins stated that Beck was “a very important witness” who was submitted to a “very severe cross-examination” and showed himself to be “respectable in his appearance and demeanor, and unimpeached by a whisper against his veracity or general character.” Ignatius Beck was 65 years of age.[17]

The Citizen

For the next 10 years Beck was employed as a rope maker, chimney sweep, master sweep and a dealer of unspecified “material.” He would serve his community, church and family well. He died on October 14, 1849 at 75 years of age from Tuberculosis. He was residing at 31 Barclay Street (now Delancey Street) near 6th and Spruce Streets. He appear to have been living with a daughter (dressmaker) and 2 sons (seamen) near the time of his dead. His spouse is presumed deceased.[18] He is buried on Queen Street in Bethel Burying Ground where he once toiled.[19]

[1] This observation by stated by Judge Joseph Hopkinson of the U.S. District Court for Eastern Pennsylvania, The Law Reporter, editor, P.W. Chandler, vol. II, May, 1839-April, 1840, p. 110. This is available electronically at Google Books.

[2] Joseph A. Borome, “The Vigilant Committee of Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, v. 92, no. 3, July, 1968, 320-351, 339. On at least one occasion Beck was trusted by Rev. Allen to carry cash to be delivered that was collected at the Church for the benefit of The Vigilant Committee.

[3] D.E. Meaders, Kidnappers in Philadelphia: Isaac Hopper’s Tales of Oppression, 1780-1843, Second Edition, ed., E.L. Wonkeryor; Africana Homestead Legacy Publishers, Cherry Hill, NJ, 2009, 255-256; National Anti-Slavery Standard, 20 Jan 1842, 130.

[4] A “Class Leader” at Mother Bethel was someone who held weekly classes of about 12 congregants. The focus of which was to shepherd the faithful by inquiring how they were prospering and also to advise, reprove, comfort or exhort, collect funds and report the spiritual and physical condition of the participates to the ministers of the Church. The leader of such a class had to be a person of “sound judgment.” See The Doctrines and Disciplines of the A.M.E. Church, 26th Edition, 1916, 48, 59-60. This is available at Google Books.

[5] Benjamin Lundy, editor., The Genius of Universal Emancipation, a Monthly Periodical Work, vol. 1, Third Series, April 1830, p. 163.

[6] Allen, William C., History of Slave Laborers in the Construction of the U.S. Capital Building, 2005. Available at

http://artandhistory.house.gov/art_artifacts/slave_labor_reportl.pdf; Arnebeck, Bob, Through a Fiery Trial: Building Washington, 1790-1800 (NY: Madison Books, 1991); See also http://bobarnebeck.com/slavespt4.html.; Arnebeck, Bob, Slave Labor in the Capital: Building Washington’s Ionic Federal Landmarks (US: The History Press, 2014), 29, 94, 138.

[7] Allen, F.J., The Shoe Industry (NY: Holt & Co., 1922), 382; Earle, A.M., Two Centuries of Costume in America, Vol. II (NY: Macmillan, 1903), 756; Philadelphia City Directories are available at PhillyHistory.org and both books are available online at Google Books.

[8] Meaders.

[9] Rodriguez, Junius P., Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, And Historical …, Volume 2, (CA: ABC-CLIO, 20027), 251.

[10] Delaney, Martin R., The Condition, Elevation, Emigration and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (CA: ABC-CLIO, 2007), 72-75. (This book is available on Google Books.)

[11] The Ram’s Horn, November 5, 1847.

[12] Joseph A. Borome, “The Vigilant Committee of Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, v. 92, no. 3, July, 1968, 320-351, 339. On at least one occasion, Beck was trusted by Rev. Allen to carry cash to be delivered that was collected at the Church for the benefit of The Vigilant Committee.

[13] Meaders; National Anti-Slavery Standard, 20 Jan 1842, 130.

[14]See Henry McNeal Tanner, Methodist Polity, ed., A. Lee Henderson (Nashville, TN: AMEC Sunday School Union, 1986), 157.

[15] “Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803-1915,” index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/JX7L-23T: accessed 09 Jun 2014), Egnesh Beck, 19 Feb 1817; citing, Department of Records; FHL microfilm 1862806.

[16] Benjamin Lundy, editor, The Genius of Universal Emancipation, a Monthly Periodical Work, vol. 1, Third Series, April 1830, p. 163.

[17] See footnote #1.

[18] 1847 Philadelphia African-American Census at http://fm12.swarthmore.edu/1847/full.php?rid=204&trc=4308.

[19] Obit, Public Ledger, 17 Oct 1849; Death Certificate available at https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JK98-RYZ.