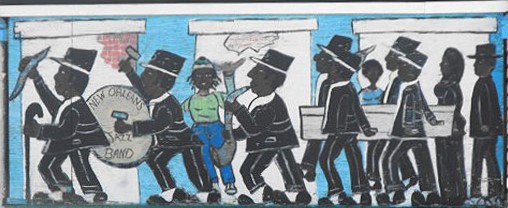

Life and death were grim for the Philadelphia African American poor on Baker Street in 1847. Many slept in windowless basements that were often flooded with wastewater. These pitch-black hellholes cost twelve cents a night that could hold dozens of men, women, and children who usually stayed during cold weather. The backyards of these hovels were filled with 6′ x 6′ windowless wood boxes with dirt floors that were frequently wet and flooded when it rained. There were no chimneys, so a hole was cut in the door to allow smoke to escape from cooking fires. Sometimes eight humans were found living in one of these huts. Grotesquely, it was not uncommon to have someone die in one of these and a new resident would move in before the body could be removed by the authorities. These living conditions were perfect for spreading deadly diseases. The white newspapers mockingly called this block the “Arcade,” as in a human zoo. (1)

The Spring and Summer of 1847 Philadelphia were especially bad. The weather was awful, along with the mosquitos, the rats, the fleas, and the water. Pigs and wild dogs freely roamed the streets, adding their fetid waste to that of the working horses of cart and carriage. September arrived with little change. The residents were dying by the dozen and bodies were piling up. Thirty in one week. Baker Street had become a slaughterhouse.

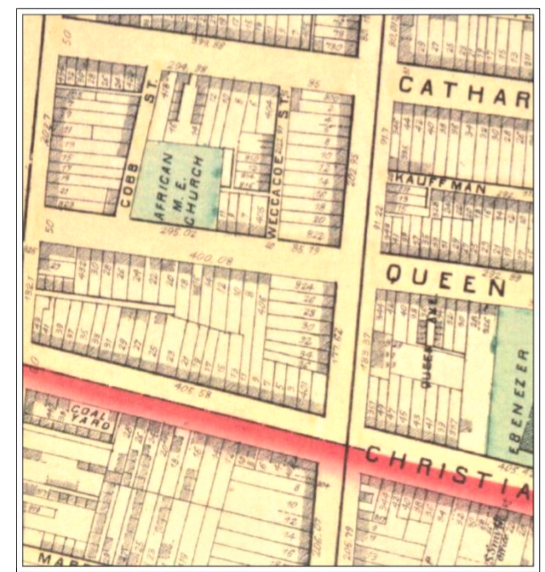

One thousand thirteen Philadelphia children died of Scarlet Fever in 1847. The cemeteries couldn’t keep up with the demand. The Black cemeteries were small and few. The corpses were piling up at Bethel Burying Ground and there wasn’t enough time to bury everyone in a six-foot-deep grave. The small cemetery did not have a vault to store bodies waiting for interment. The Bethel cemetery was not the only Southwark burial ground to be cited for the same conditions.

W.J. Mullen was the slumlord who owned the majority of the structures on Baker Street. On his own, and I suspect with the help of the local white gang, forcibly removed the majority of the destitute on Baker Street. He didn’t do this with a good heart. He wanted the buildings and shacks torn down so he could either sell the properties or rebuild and rent to families that could afford much higher rents. His heavy-handed actions created a backlash that required Mullen to ask for police assistance to protect his henchmen. Within days, people were sneaking back into their homes. It was winter and Baker Street was better than nothing. To the surprise of no one, a fire broke out in the early morning of December 11th in one of the structures and spread quickly through the old wooden structures. The fire companies later stated they had problems putting out the fires because of the “numerous obstructions” they encountered. They did succeed in suppressing the flames after the damage was done. (3)

Baker Street wasn’t the first Black neighborhood this happened to. Nor would it be the last.

(1) A Statistical inquiry into the condition of the people of colour, of the city and districts of Philadelphia, Walton, 1849; Philadelphia Inquirer, 8 Nov 1847, p. 2.

(2) Public Ledger, 8 Nov 1847, p.2; Dollar Newspaper, 1 Dec 1847, p.3.

(3) Philadelphia Inquirer, 18 Dec 1847, p. 1.