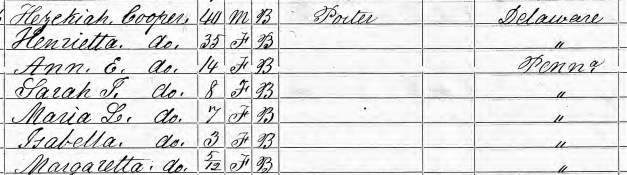

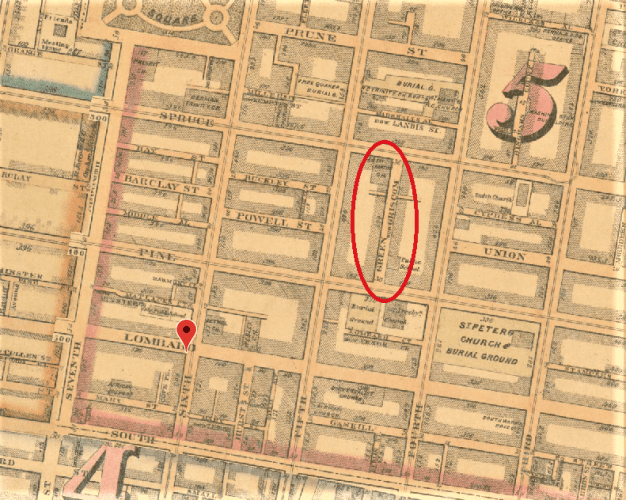

Fifty-four-year-old Dinah Johnson died this date, May 2nd, in 1854 of Tuberculosis and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. (1) She worked as a laundress and was a native of New Jersey, according to the 1850 U.S. Census. Ms. Johnson lived in a building at 184 Pine Street which was between 6th and 7th Streets. For this, she paid $4 a month in rent. (2) This was a hefty amount for rent. However, the 1847 Census shows that she was living with two other female adults and a female child at this address. Their relationship was not documented. One of the other women worked as a laundress while the other as a seamstress. Three members of this family were not native to Pennsylvania. Four could read and three could write. All the women regularly attended church services and belonged to a beneficial society.

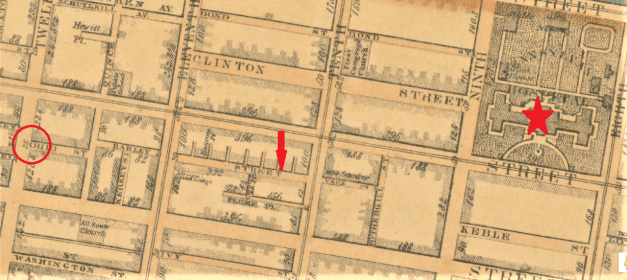

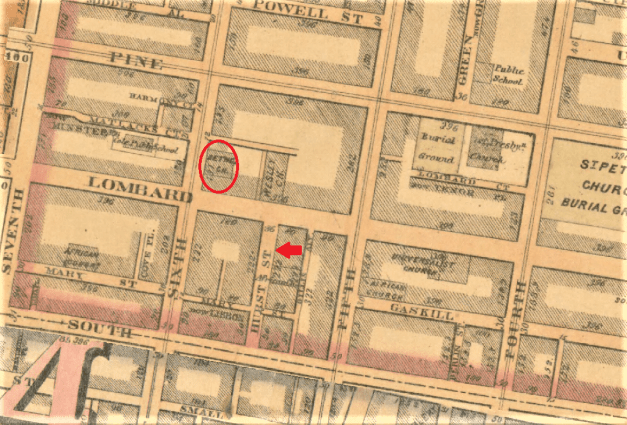

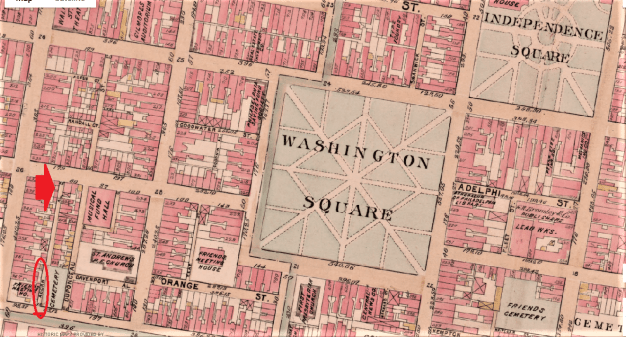

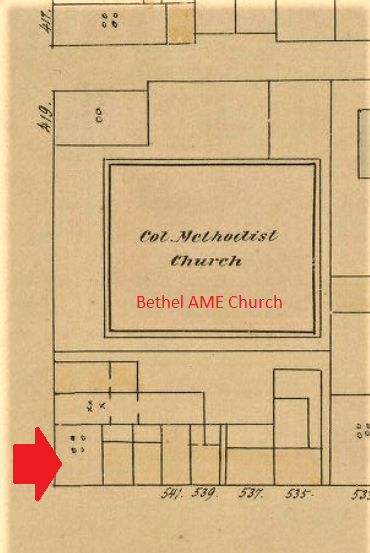

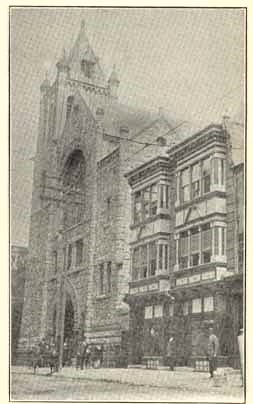

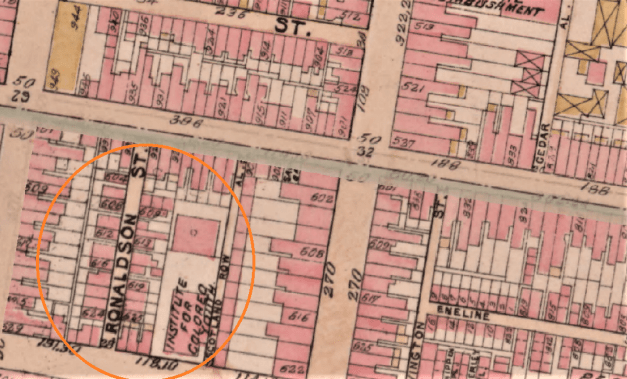

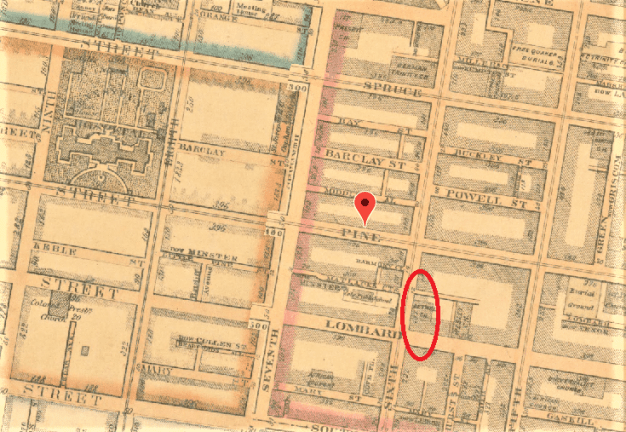

The red pin illustrates the location of Ms. Johnson’s home. The red circle marks the nearby location of Bethel AME Church.

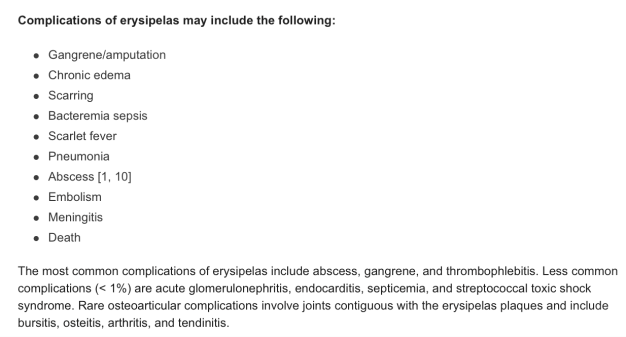

It is not known how long Ms. Johnson was sick with Tuberculosis. There was generally known to be two types of the illness: “chronic” that could go on for years or “galloping consumption” which would kill in a matter of weeks. No matter which one plagued Ms. Johnson, she probably went to Mr. Zolhekoffer’s drug store on her street corner to purchase the medicines that would help with the violent coughing, diarrhea, and blood-spitting that accompanied the disease. She also may have purchased a compound that would help her sleep for a few hours. According to the Philadelphia Board of Health, Ms. Johnson was one of the 1,394 citizens to die in 1854 due to Tuberculosis of the lungs.

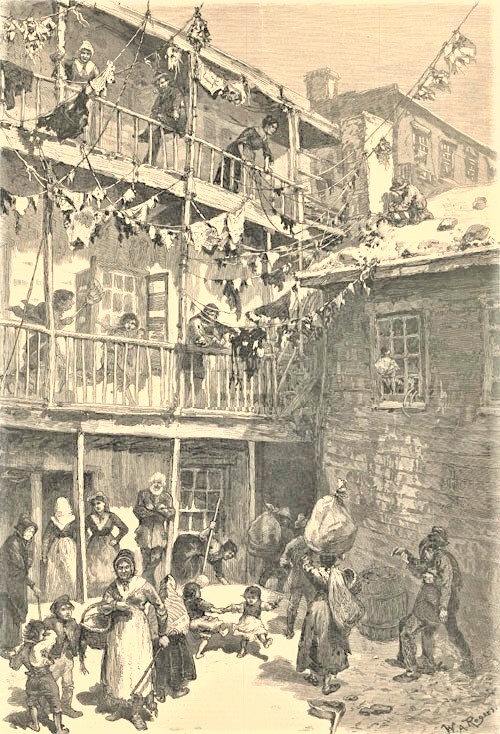

With families packed into one or two poorly ventilated rooms, the Tuberculosis bacteria could infect and kill an entire family.

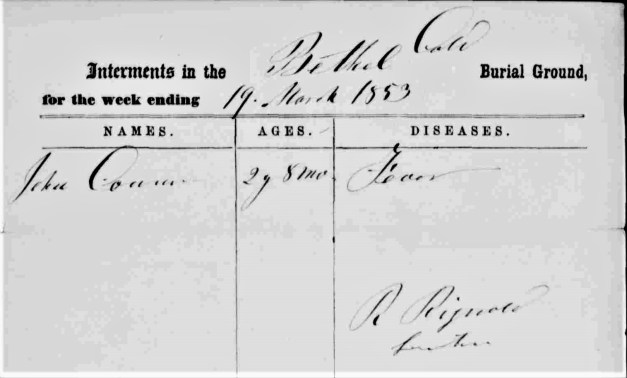

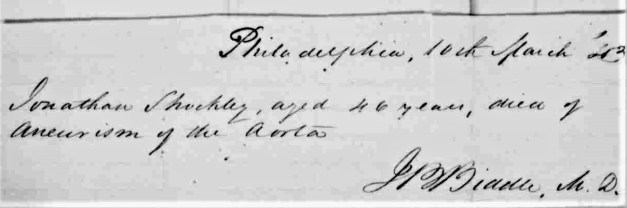

Ms. Johnson died on a early day in May in 1854 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground.

(1) The spelling of Ms. Johnson’s first name was also reported as “Diana.”

(2) The social worker interviewing Ms. Johnson in 1847 reported that “She (Ms. Johnson) probably gains her rent by letting out houses.” I take this to mean she acted as a representative of the tenement owner and managed the rentals for the owner.