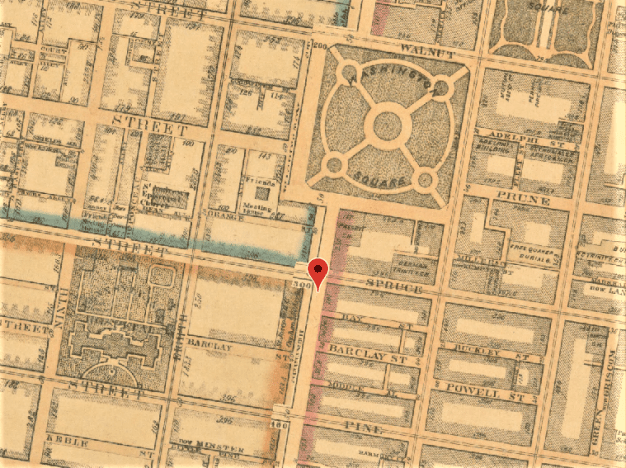

Thirty-one-year-old Jane Potter died this date, July 15th, in 1849 of Cholera and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. She was born in Maryland and came to reside in Philadelphia in 1826 when she was eight-years-old. At the time of her death, she was married and labored as a domestic worker. There is no additional personal information on Ms. Potter nor her spouse.

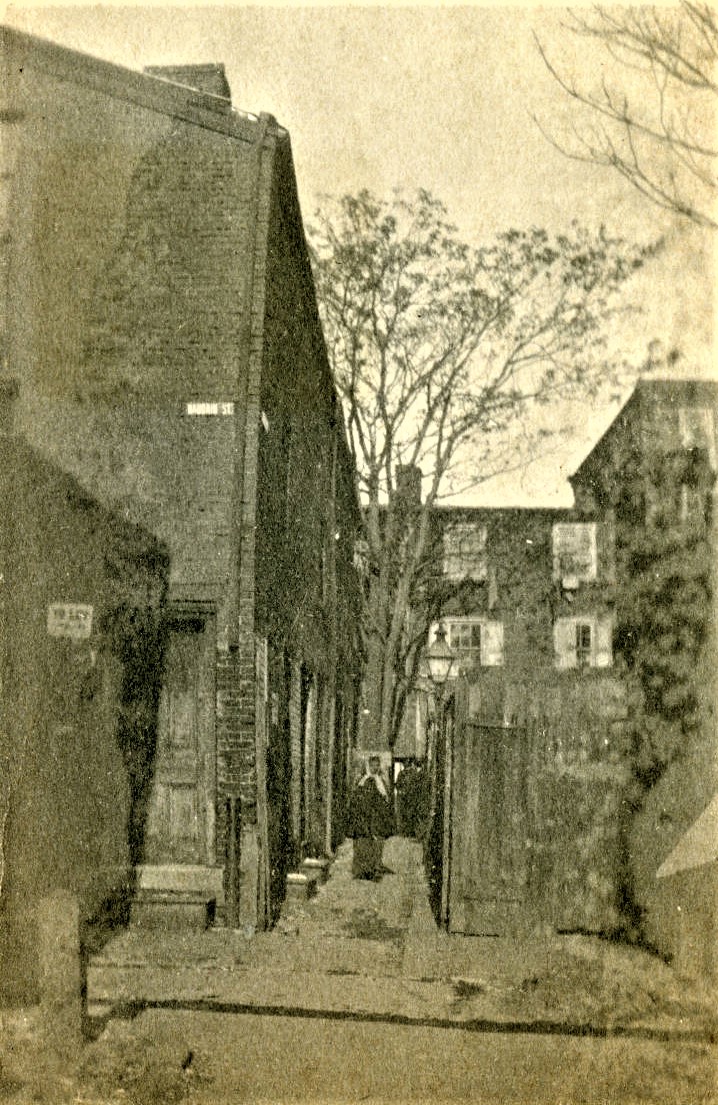

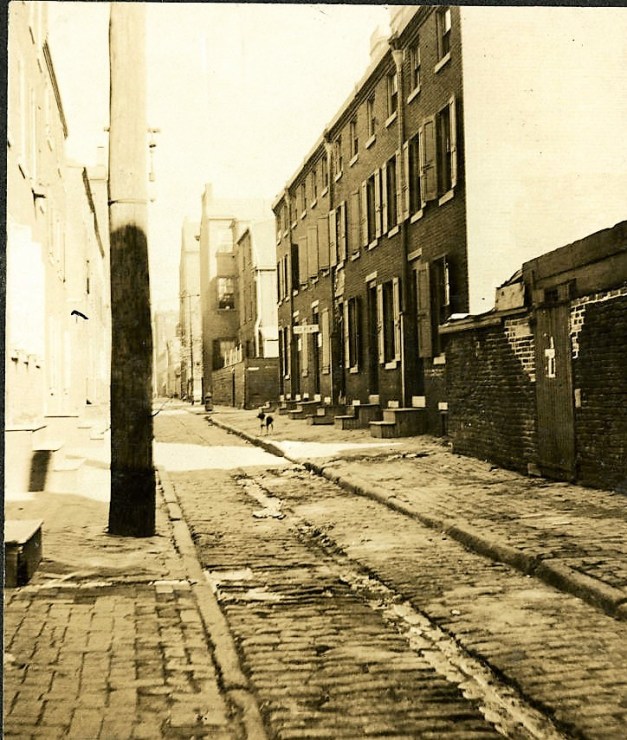

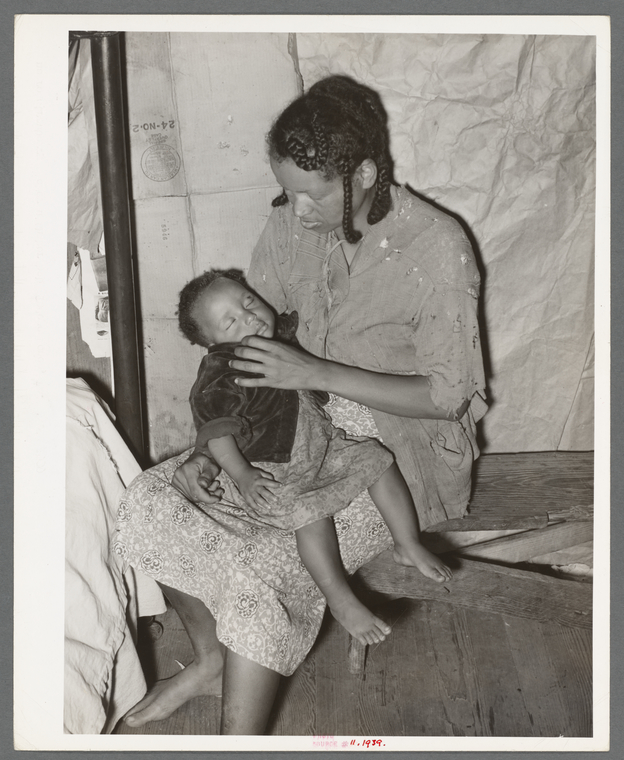

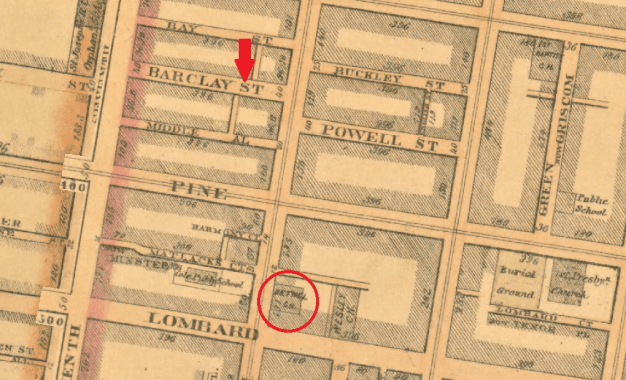

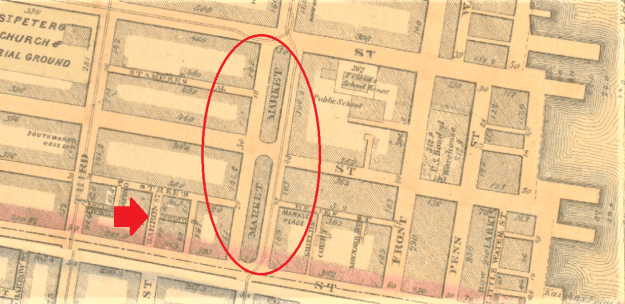

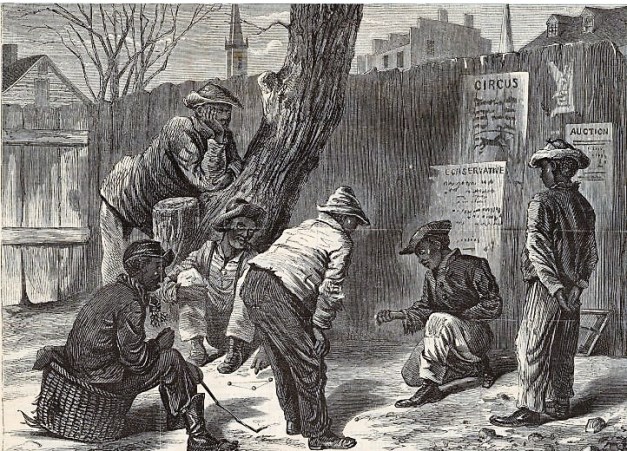

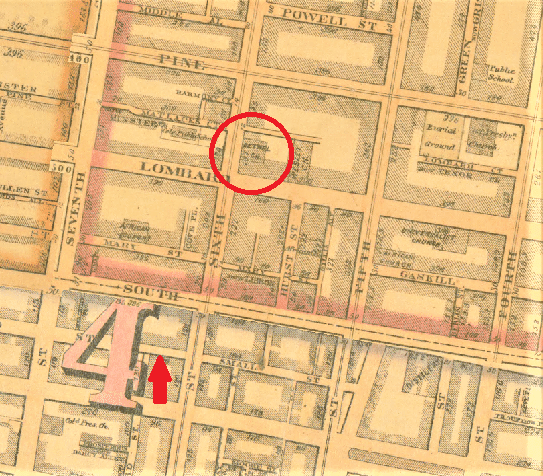

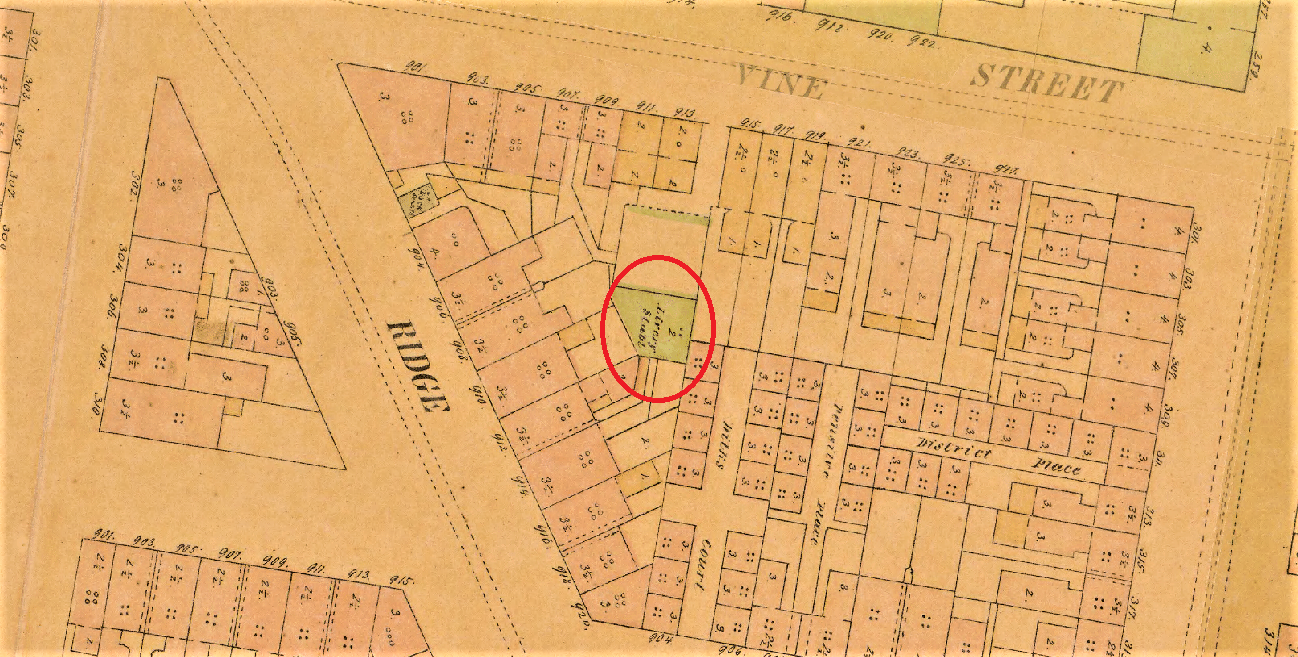

In 1849, Ms. Potter lived on Lombard Street which was the center of the Black population in the city. Bethel AME Church at 6th and Lombard was its keystone. In addition to the activities around the church, during the week Ms. Potter would have seen and heard the dozens of young children being brought by their parents to the Lombard Street Infant School. Two Black teachers provided daycare and teaching for two-to-five-year-old Black children. The school was financed by the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery.

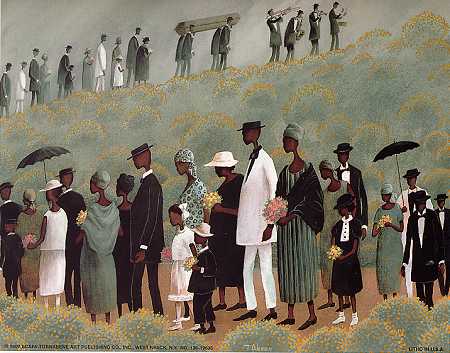

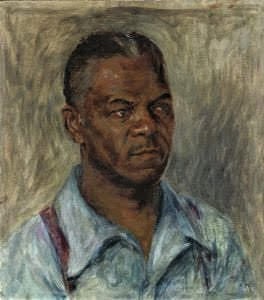

Ms. Potter may have been one of the mourners at the funeral of Bishop Morris Brown on May 20th in 1849. He was the second Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the protege of Bishop Richard Allen. It was a Sunday afternoon when the coffin was carried on a bier by ministers wearing flowing white scarfs. After them came others with scrolls, representing the six conferences over which Bishop Brown presided. Hundreds of mourners came next and after them came the daughters of the conference, one hundred and seventy in number, each being “uniformly clad in the deepest mourning. ” (1)

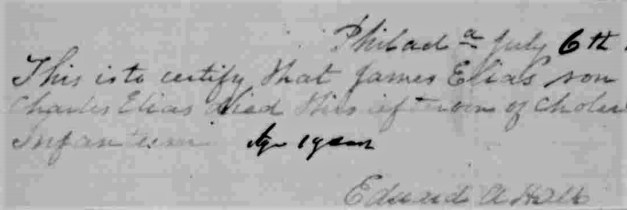

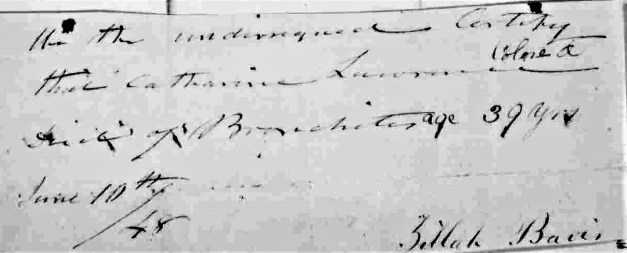

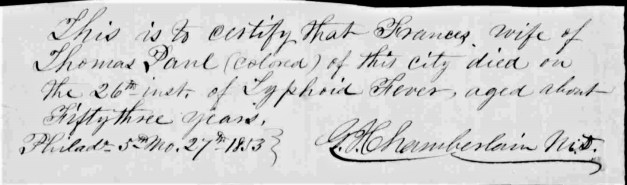

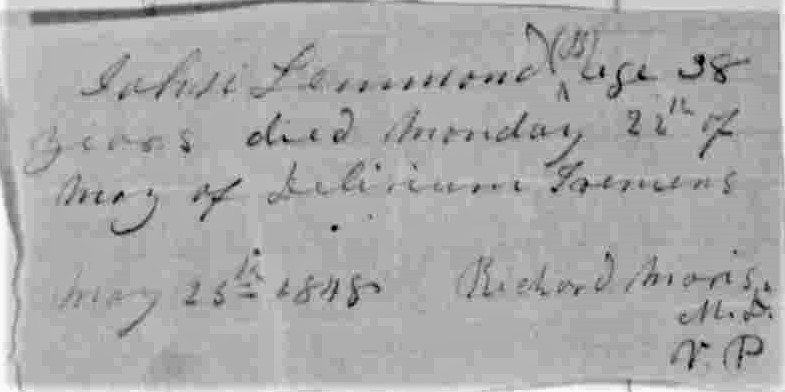

Ms. Potter may have been very sick by this point and realized her time on earth was limited. As the coffin passed her by, thoughts might have been of her last days. Ms. Potter’s death certificate was signed by Black physician J. J. Gould Bias. For more information on the Bias family, please click on the link below. (2)

New York Library Digital Collection

Ms. Potter died on a relatively cool day in July where the temperature rose to only 76° by midday, accompanied by a slight breeze out of the north. She was buried by her family, with dignity, at Bethel Burying Ground.

(1) The Liberator, 25 May 1849.

(2) BIAS

![Public_Ledger_1841-08-23_[3]](https://bethelburyinggroundproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/public_ledger_1841-08-23_3.png)