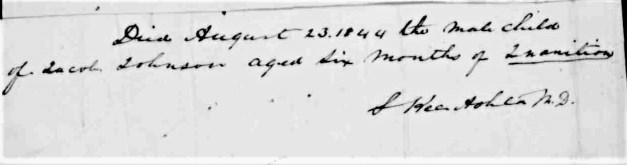

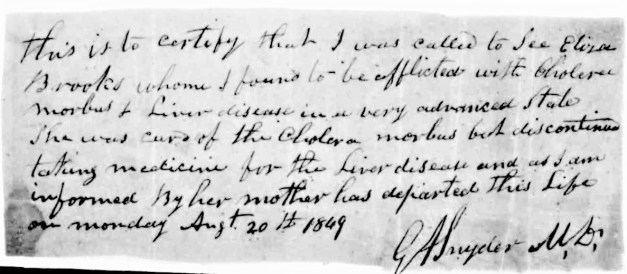

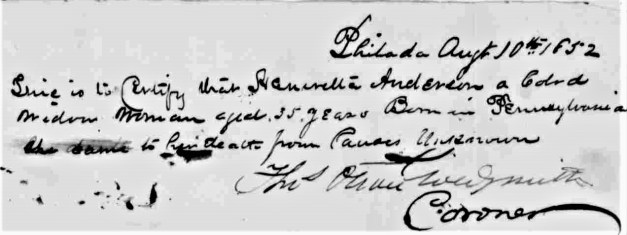

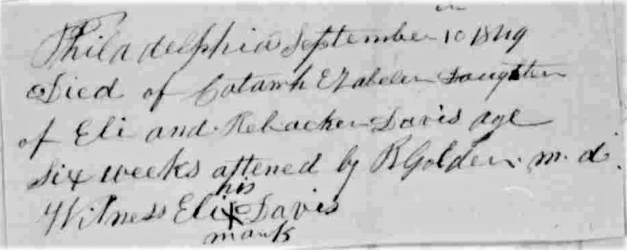

Six-week-old Isabella Davis died this date, September 10th, in 1849 from an undiagnosed illness that caused a fever (Catarrh). Eli and Rebecca* Davis were sixty-four and forty-four years of age respectively when the infant died, according to the 1850 U.S. Census. Also in the home were ten-year-old Rebecca and two-year-old Benjamin. Mr. Davis was born in Maryland** and Ms. Davis was born in Pennsylvania as were all the children, according to the 1850 Census.

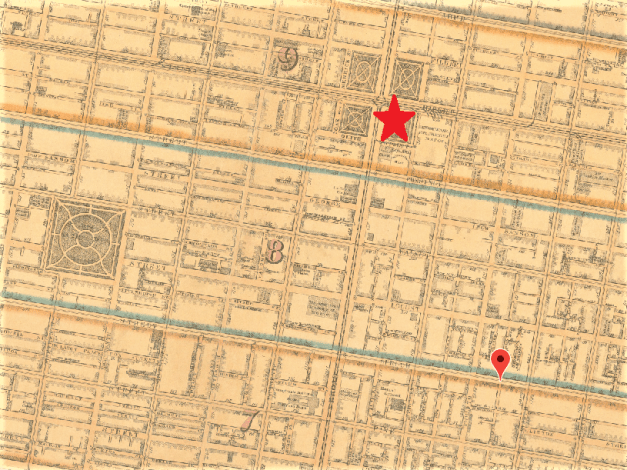

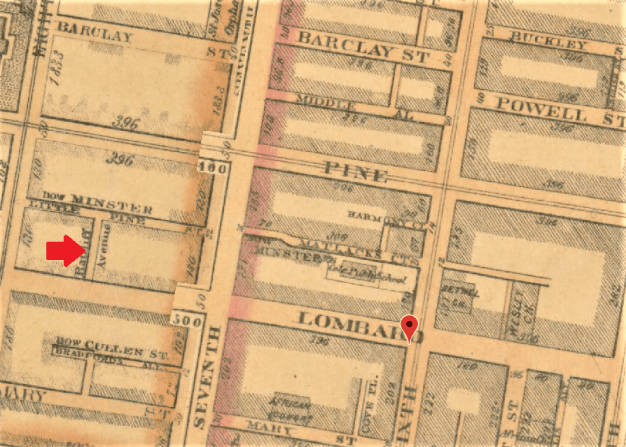

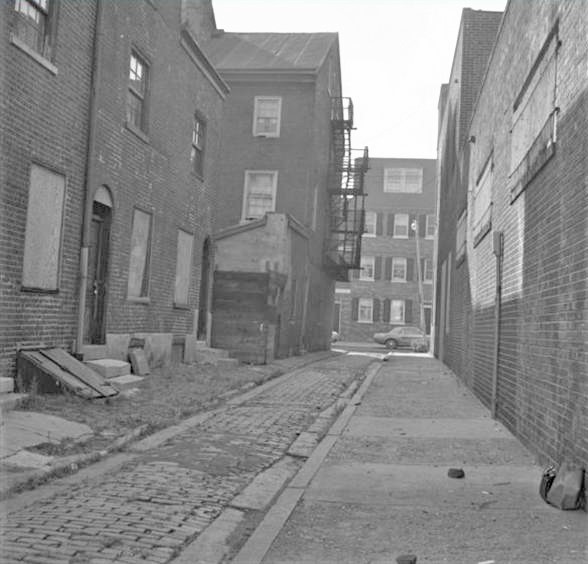

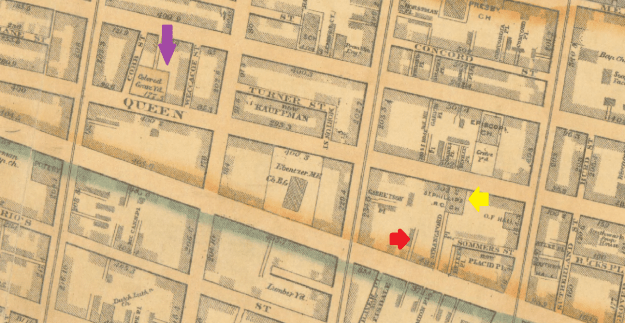

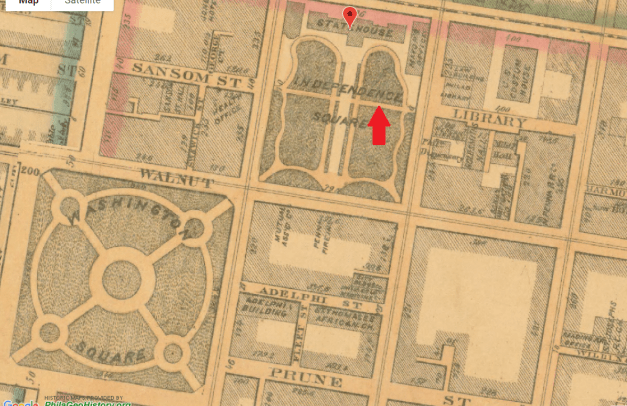

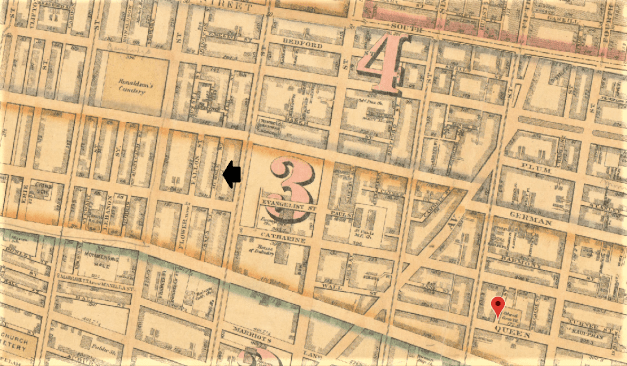

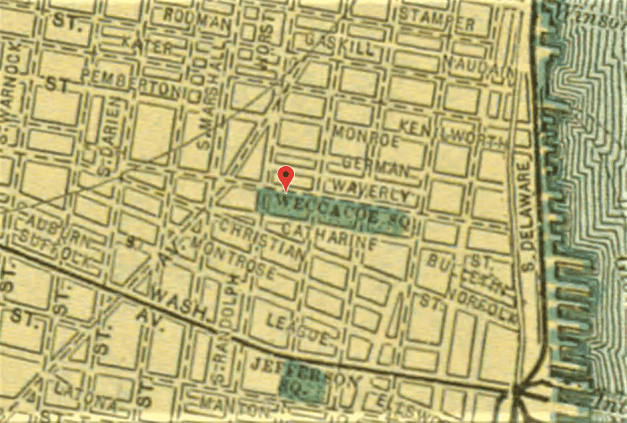

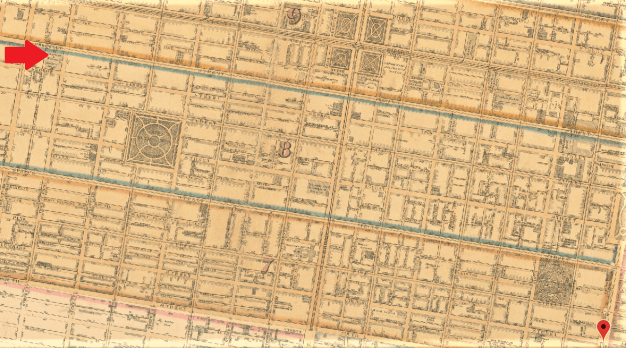

Eli Davis was a self-described “cake dealer” with a shop at 7th and Lombard Streets a block away from Bethel A.M.E. Church. This location is illustrated by the red pin in the lower right-hand corner of the above map. The red arrow in the upper left-hand points to the Davis family home at 17th and George Street (now Samson Street). In the 1850 U.S. Census, Mr. and Ms. Davis valued their property at $2,000 or approximately $66,000 in modern currency. In the 1847 Philadelphia African American Census, it was reported that Mr. Davis earned $6 a week and Ms. Davis earned $.50 a week as a laundress. The census also reports that Mr. Davis was a Freemason.

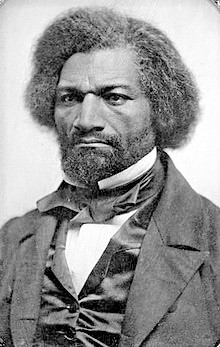

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

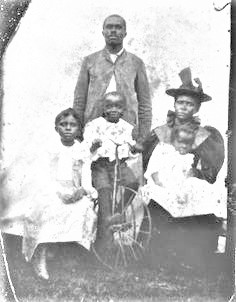

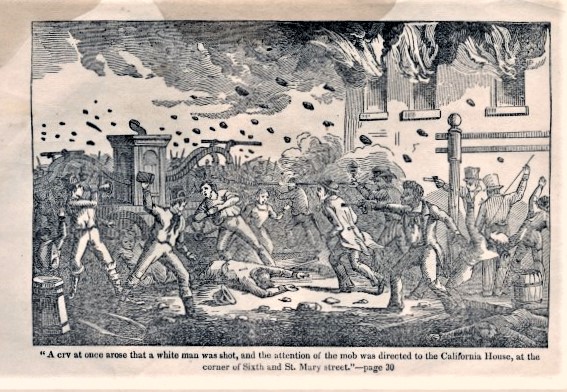

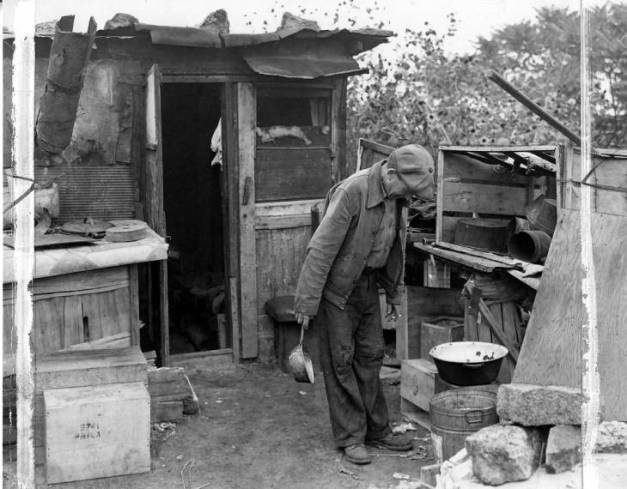

The day before six-week-old Isabella Davis died, “a gang” of white men invaded the home of a Black man living near the Davis’ home. He was severely beaten “in an act of wanton wickedness on the part of the assailants,” according to a newspaper report.*** Sadly, this type of violence against African Americans was common, while the white police force literally stood by and watched. Black men and women were hunted in their own communities.

Speaking in Philadelphia the following Spring, Frederick Douglass had this to say about the racist violence in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia from time to time, the scene of a series of most foul and cruel mobs, waged against the people of color – and is now justly regarded as one of the most disorderly and insecure cities in the Union. No [Black] man is safe- his life – his property – and all that he holds dear, are in the hands of a mob, which may come upon him at any moment – at midnight or mid-day, and deprive him of all.****

Those buried at Bethel Burying Ground, in addition to living under apartheid conditions, had to fight everyday just to survive.

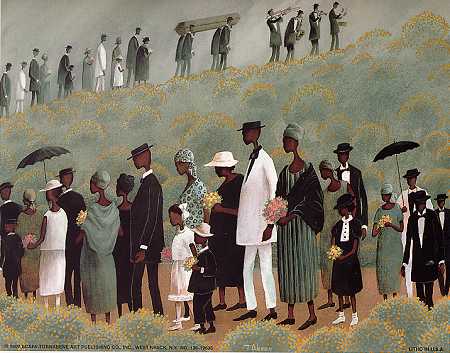

Rebecca and Eli Davis lost their infant daughter on a clear September day with a light northerly wind. The temperature never made it out of the mid-60s. She was buried at Bethel Burying Ground.

*It appears that the doctor misspelled Ms. Davis’ first name. The 1850 U.S. Census has her named as “Rebecca,” as does her death certificate.

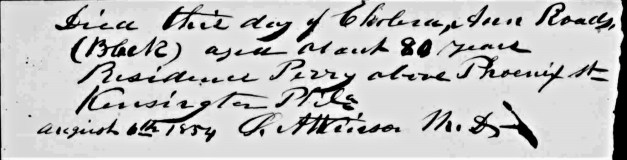

** On Ms. Davis’ death certificate in August of 1857, Eli Davis’ place of birth was reported as Nantucket, Massachusettes.

***North American, 11 September 1849.

****The North Star, 30 May 1850.

Note: This posting is a revision of one from one year ago. That one has been deleted.