Margaret Shorter, 55 years of age, died this date, July 24th in 1849 after suffering a stroke. Sadly, little else is known about Ms. Shorter. She lived on Cobb Street which is across the street from Bethel Burying Ground. It is very likely she lived at #3 Cobb Street and was a live-in domestic for the African American Brister/Parker family. For further reading on this family, I suggest going to http://www.archives.upenn.edu/people/1800s/brister_james.html.

African American cemeteries

All posts tagged African American cemeteries

Robert Howard, 63 years old, died this date, July 21st, in 1849 of Cholera and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. From the records of the 1847 African American Census, it appears that Mr. Howard lived with his spouse, several children and possibly his or her’s parents and/or grandparents. There was one female in the family over 100 years old. The Howard family lived in Acorn Alley (now Schell St.) which ran between 8th and 9th streets and Bainbridge and Fitzwater streets in south Philadelphia. He worked as a cook and Ms. Howard took in washing to add to their income. The Howards were neighbors of the Reverend John Boggs an AME minister of some prominence. Rev. Boggs died a little over a year before Mr. Howard.

Tragically the city was being ravished by Cholera in the summer of 1849. Mr. Howard was one of 196 individuals that died in the city and county of Philadelphia the same week as he did. Twenty-eight people a day were dying from the disease. (Public Ledger, 25 July 1849, p. 2.)

Eight-seven-year-old Sarah Bass Allen died this date, July 16th, in 1849 of “old age” and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. She was born enslaved in Virginia and in 1794 at approximately 20 years old is listed in The Philadelphia directory and register, 1794″ as living as a free person at 13 Shippen Street in the Southwark district of the county. Ms. Bass reported her occupation as “washerwoman.” She married the Reverend Richard Allen, founder of the AME Church, on August 12, 1801. The Allens had six children Richard L., James, John, Mary Ann, Peter and Sarah. (1)

Sarah Allen is revered in the AME Church as “Mother Allen” and “First Mother. She is hailed for her vigorous support of her husband and other AME ministers in their mission to spread the doctrine of the Church. She is also known for her courageous nursing service during the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1793. (2) In addition, she is reported to have been an active conductor on the Underground Railroad. (3)

It appears Sarah Allen was initially buried at Bethel Burying Ground instead of ground around Bethel Church because of ongoing construction. At some point, her remains were buried on church ground and in 1901 was placed next to her husband’s remains in a crypt in the basement of the church. (4)

(1) Aaron Goodwin, “The Richard Allen Family,” Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine, vol. 47 (2011), 215-47.

(2) J.M. Powell, Bring out Your Dead, p. 101.

(3) Jessie Carney Smith, Freedom Facts and Firsts, p. 237.

(4) Carol V. R. George, Segregated Sabbaths; Richard Allen and the emergence of independent Black churches 1760-1840

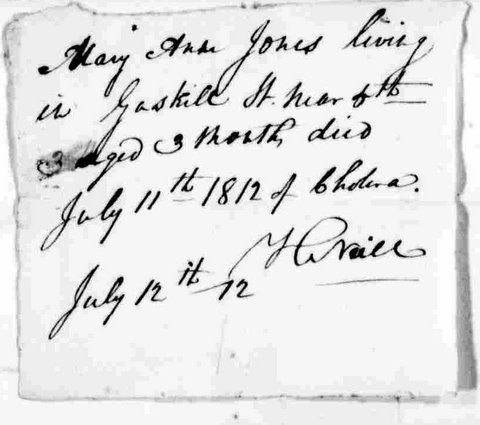

Three-year-old Mary Ann Jones died of Cholera on this date, July 12th, in 1812 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. I could not find any further information on her family, however, historian Gary Nash* had this observation about Gaskill Street.

“Gaskill Street, A narrow street running only three blocks from 2nd to 5th between Cedar and Lombard, had only one black household indicated in the 1793 yellow fever survey, only two listed in the 1795 directory, and only three recorded in the directory of 1811. But five years later 24 black families were spread along Gaskill, 22 of them in the block between third and fourth Street. . . . The 24 black families on Gaskill Street in 1816 lived in a neighborhood formed a nearly perfect cross-section of Philadelphia’s industrious middle and lower classes.”

Richard (aka Rich) approximately 50 years old, died this date, July 9th, in 1813 of Hydrothorax* and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. He was an enslaved Black man (“a Negro Slave”) imprisoned by John Stille, a wealthy Philadelphia merchant who was now deceased and so consequently Richard was now “belonging” to the Steele estate.

Between 1790 and 1800, the number of enslaved in Pennsylvania dropped from 3,737 to 1,706. Three years before Richard died (1810) there were 795 and by 1840, 64 bondsmen in the state. By 1850, there were none.* For further reading on the subject, I recommend Forging Freedom by Gary B. Nash.

*Fluid builds up in the chest cavity around the lungs and suffocates the victim. Causes can be from different diseases or heart or liver problems.

**http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/empowerment/18325/gradual_abolition_of_slavery_act/623285).

On Saturday night June 22nd Ben Smith, a Black man, was arrested with a corpse in his possession that he just stole from Bethel Burying Ground. The body was probably that of 25-year-old Maria Krumbach who died of Tuberculosis on the 18th and was likely buried on the 20th or 21st. The medical schools required that their dissection specimens be fresh. Smith, the body snatcher, was brought before an alderman (magistrate) and committed to the county prison. I was unable to find any further information on this “resurrectionist.”*

Robbing graves for the bodies of the recently deceased goes back many centuries and started in the United States in the late 18th century to help meet the demand for “hands-on anatomical dissection” for teaching medical students the geography of the human body.** These acts were not only done by men skulking around a cemetery in the dark of night, but also by the men who buried the dead and were responsible for the management of the burying ground. In the early 1800’s it was observed that the superintendent of Philadelphia’s Potter field was so open about his selling of the dead that in the backyard of his home were ” . . . piles of boards and broken coffins. The bodies having been sold, the coffins used for firewood.”*** Shocking examples of this kind of crime was not uncommon in Southwark and Moyamensing where the small police force was unable to protect the cemeteries forcing outraged citizens to organize mobs and attack medical schools and known grave robbers.****

“In December 1882, a reporter from the Philadelphia Inquirer, acting on a tip, caught grave robbers at work at the Lebanon cemetery, the burial ground for Philadelphia’s African Americans. . . . The robbers claimed that they were hauling bodies to Jefferson Medical College where they were paid for their services by William Forbes, Chief Anatomist. . . . A crowd of angry Philadelphia African Americans gathered at the city morgue and demanded protection of their grave sites from the city.” When winter ended and the snow melted away the city’s cemeteries looked as if “they had been subjected to an aerial bombardment” because of all the open and empty graves. The Lebanon superintendent confessed that for many years he had let grave robbers “steal as many corpses as they could for sale for anatomical dissection.”****

There is no way to tell how many graves were robbed at Bethel Burying Ground. We know that has long as the thieves were robbing the graves of Blacks and poor whites there was no incentive to pass stricter laws. The line was crossed when bodies of prominent white citizens started missing provoking white legislatures to enact laws that made it easier for medical schools to obtain corpses and lengthening terms for the captured “buzzards.” (Halperin)

——————-

*Public Ledger, 10/25/1842. The terms “resurrectionist,” “grave robber,” “body snatcher” and occasionally “buzzard” were used to identify these thieves.

** Christine Quigley, The Corpse: a history, p. 290-301.

***John Fanning Watson, Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden Times, p. 363. Available online at Google Books.

**** Simon Baatz, “‘A Very Diffused Disposition:’ Dissecting Schools in Philadelphia, 1823-1825,”Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol.108, number 2, April 1, 1984. Available at https://journals.psu.edu/pmhb/article/view/43981.

Elizabeth Ballard, 20 years old, was shot in the abdomen in the early evening of Friday June 6, 1845 and died at Pennsylvania Hospital on June 11th. She was buried at Bethel Burying Ground.

ATTEMPTED MURDER AND SUICIDE – George Southard, colored, late barber, in Fifth street above Chestnut, while in a house in a court running from St. Mary street above Seventh, yesterday afternoon, between five and six o’clock, in company with a mulatto girl named Elizabeth Ballard, deliberately shot the female with a pistol, and then blew his own brains out with another. . . . Jealousy was the cause of the shocking tragedy. Southward was a man of respectability and leaves a wife, and a son nearly grown. He had exhibited evidence of partial mental derangement for some time. At the time of the occurrence, he was in a room alone with the young woman. He was dead when the room was entered. . . . (From the June 7, 1845 edition of the North American, p. 2.)

For further reading on the exploitation of Black women during this era, I recommend reading Colored Amazons by Kali N. Gross and The Afro-American Woman: Struggles and Images by Sharon Harley and Rosalyn Terborg-Penn.

Louisa Brown, 67 years of age, died this date, June 8th of Dropsy* and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. According to the 1847 African American Census, she worked as a domestic and was not born into slavery. Mrs. Brown lived with her husband Marcus at #6 Bonsall Street below 10th Street. The address is now in the 900 block of Rodman Street, which is between South Street and Lombard streets.

Marcus Brown was well known to the Bethel Church community. He became a close friend of Reverend, later AME bishop, Morris Brown (no relation). They came north together in 1822-23 from Charleston, South Carolina after both were implicated in the Denmark Vesey revolt.**

Marcus Brown was born in African, kidnapped and enslaved in Charleston, South Carolina. His freedom was purchased, with the assistance of Rev. Brown, for $700 according to the 1847 African American Census. Once in Philadelphia Marcus was permitted to preacher under the supervision of Morris Brown.

He was perfectly illiterate, and could not utter the simplest sentence in more than a plain exhortation, except when he was telling his experience, as he very often did. He was the most illiterate man that was permitted to occupy the pulpit of old Bethel. He was a local man to be sure, but he had an influence over his inferiors. He was a good man, [sic] and ended his career in peace.***

Marcus Brown died the same year as his wife according to Bishop Payne. I can find no official record of his death. I would presume that he would also be buried at Bethel Burying Ground next to Louisa.

*An old term for the swelling of soft tissues due to the accumulation of excess water. Today one would be more descriptive and specify the cause. Thus, the person might have edema due to congestive heart failure.

**A Will to Choose” The Origins of African American Methodism by J. Gordon Melton, p. 158 – 160.

***History of the AME Church by Daniel A. Payne, p. 317. (Available online at Google Books)

The one-year-old daughter of John B. Smith died of Catarrh Fever on this date, June 6th, 1848 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. The Smith family lived at the southeast corner of 10th and Christians streets where they ran a used clothing business out of their home. Ms. Smith was a seamstress and another adult in the family also worked in the store according to the 1847 African American Census. They paid $150 a year in rent. Mr. Smith reported his yearly income at $350.00.

This is a current photo of the S.E. corner of 10th and Christian streets in the old Moyamensing neighbor.

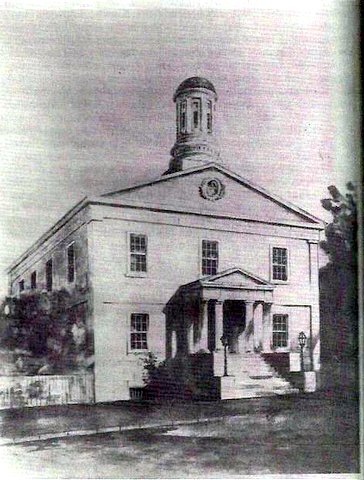

The Smith family lived a half block from Moyamensing Hall (aka Commissioners Hall) in the middle of the 900 block of Christians Street on the south side. It was the city hall for the district and functioned as the local governmental headquarters with Alderman courts, police station, morgue, and jail. It would not have been easy or safe living for the Smiths so near the center of Irish power. In addition, the neighborhood was plagued with political party riots, gang wars and race riots that involved outright acts of savagery against Blacks. The white gangs with the monikers “Killers” and “Stingers” vandalize, raped and killed with impunity. For further information see “Hunting the Nigs” in Philadelphia: the Race Riot of August 1834 by John Runcie. It is available at http://journals.psu.edu/phj/article/view/23611/23380. Also see the 10/18/1834 edition of the National Gazette and the January 3, 1848 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer.