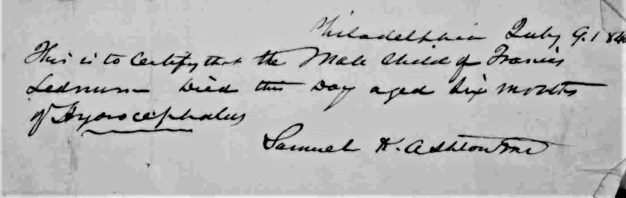

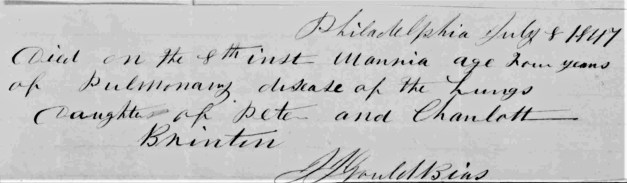

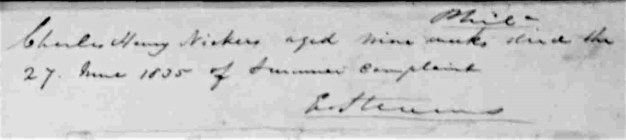

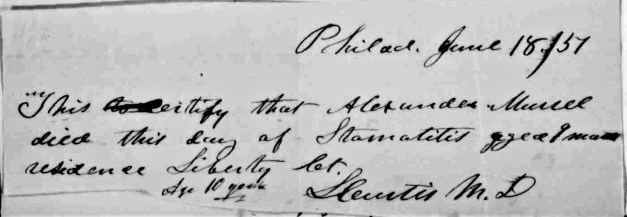

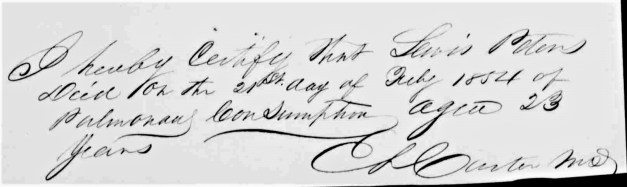

Twenty-three-year-old Lewis Peters died this date, July 21th, in 1854 of Tuberculosis and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Information about his occupation is allusive but he may have been employed as a porter at one time, according to the 1847 Philadelphia African American Census. He was the member of a family led by Rachel Peters and Sarah Boggs. They were sixty-one-years-old and sixty-four-years-old respectively at the time of Mr. Peters’ death. Both were born in Maryland and may have been sisters.

The 1850 U.S. Census lists the remaining members of the family as Mary A. Peters, twenty-six-years-old years old, and Rebecca Peters, twenty-five-years old. Both were born in Maryland and the ages listed above were as of 1850. Also in the family was John Boggs, twenty-one-years old in 1850, who was employed as a waiter.

The 1847 Census mentions that one of the family members formerly was enslaved and bought his or her freedom for $100 but it does not identify which person it was. It also reports that two women were laundresses. Also, the family regularly attended religious services and belonged to a beneficial society.

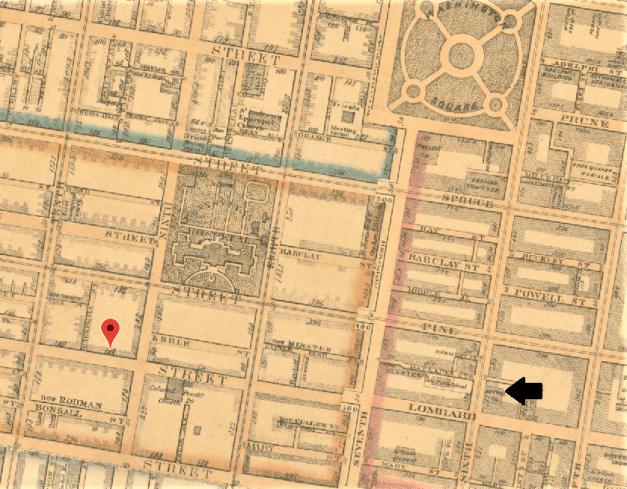

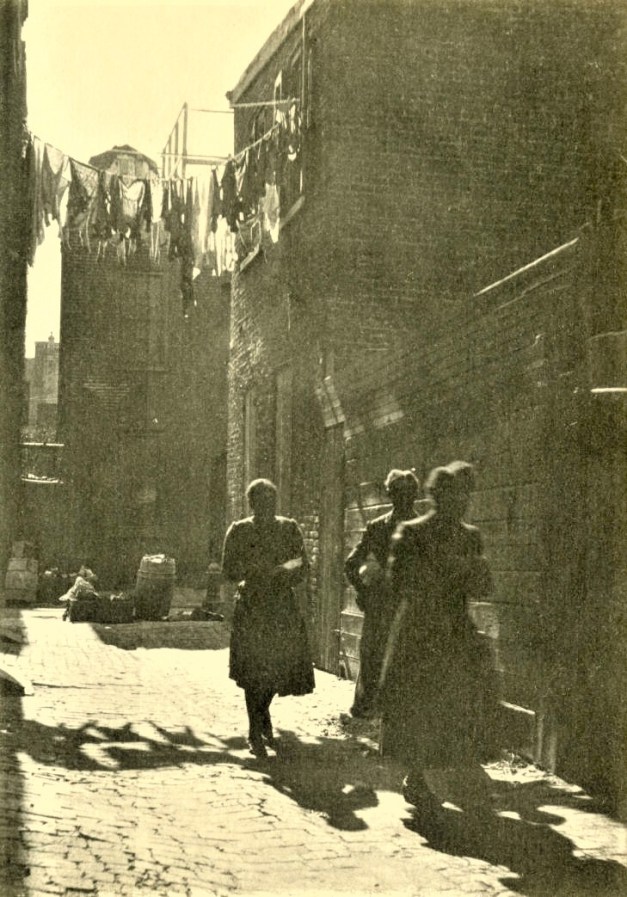

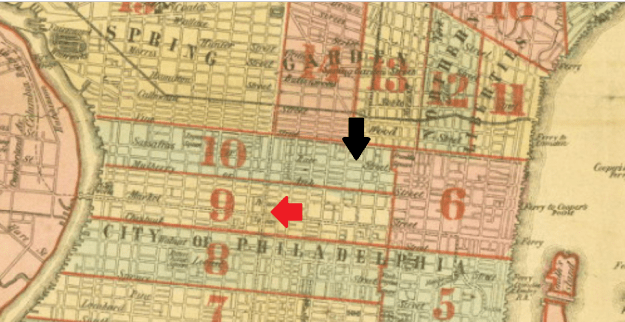

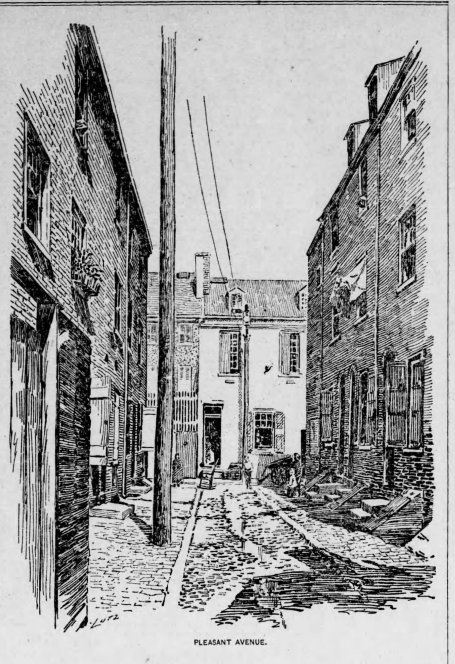

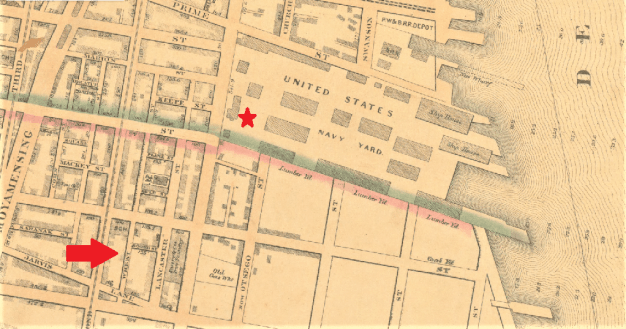

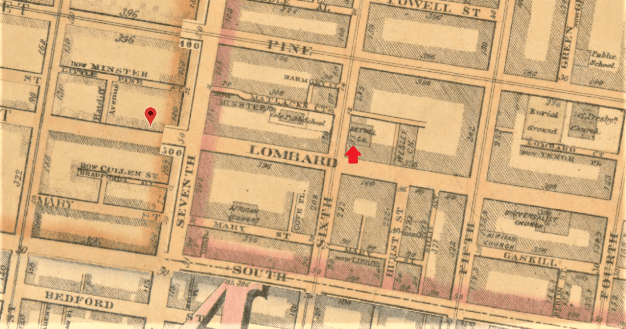

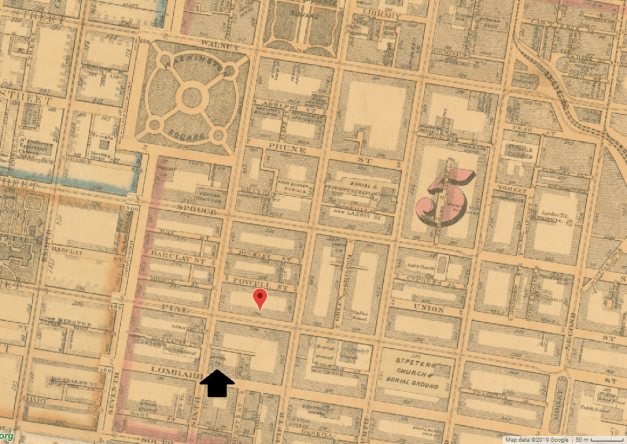

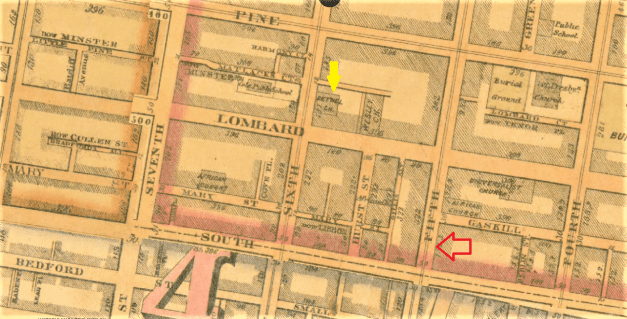

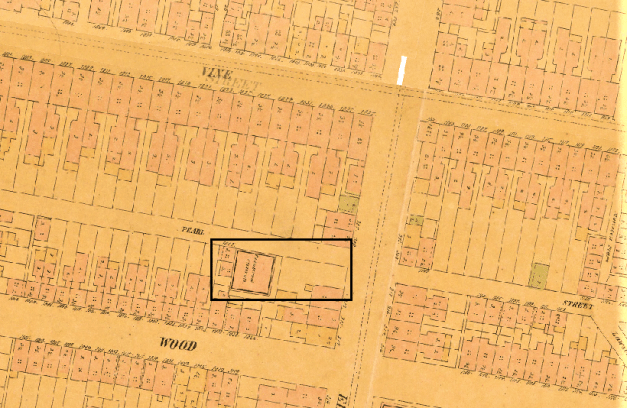

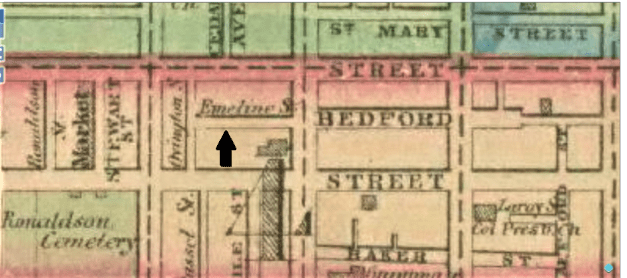

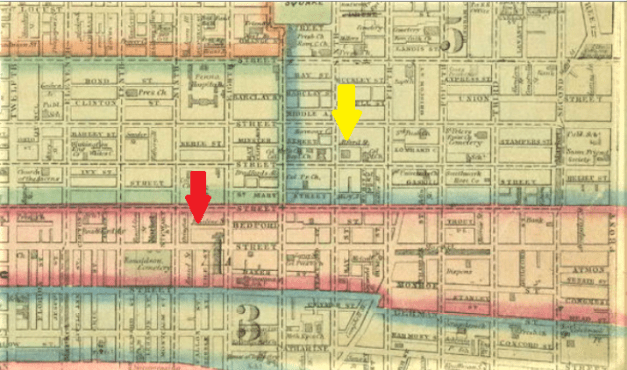

The Peters/Boggs family lived in a tenement on a small alley thoroughfare in the Southwark District of the County. The black arrow indicates the location of #10 Emeline Street.

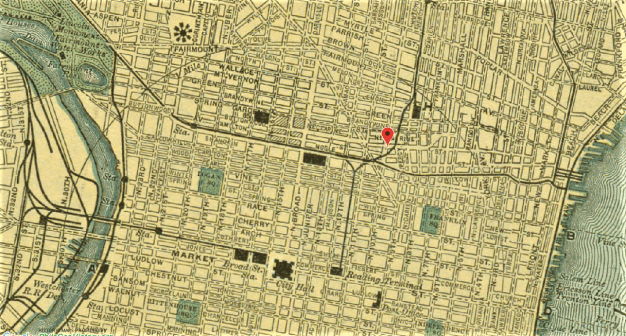

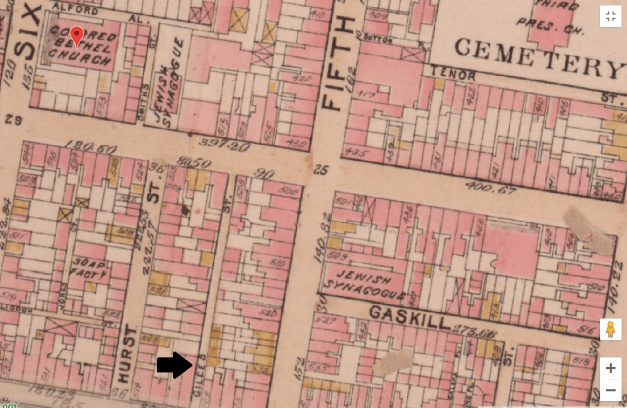

The family residence (red arrow) is shown in location to Bethel AME Church at 6th and Lombard Streets (yellow arrow).

Census records in 1847 show that there were only thirteen Black families, including the Peters/Boggs family, who lived on the small Emeline Street. These families included forty-three-members with the adults employed as dressmaker, waiter, seaman, basketmaker, seamstress, midwife, porter, and woodsawyer. Rents ranged from to $2.00 to $5.00 a month. Salaries for the men would have ranged from $2.00 to $5.00 a week. The women would have earned between $.75 to $1.50 a week.

Twenty-three-year-old Lewis Peters died on a day in July when the temperature reached a high of a “torrid” 96 degrees. His family laid him to rest at Bethel Burying Ground.