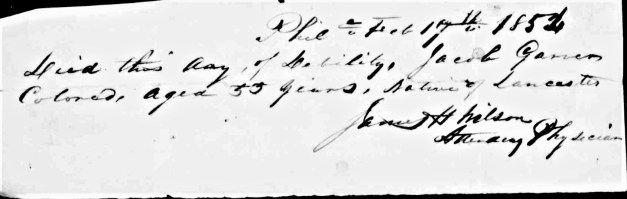

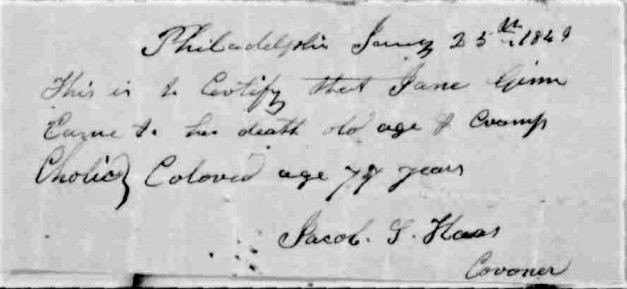

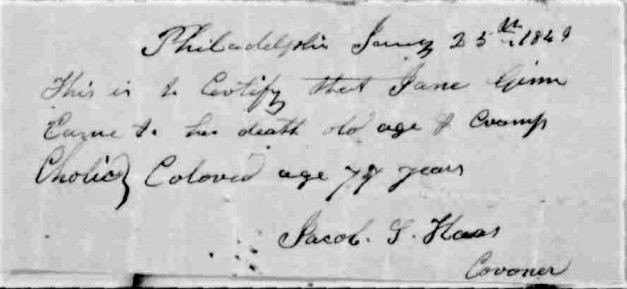

Seventy-four-year-old Jane Ginn died this date, January 25th, in 1849 of “Cramp Cholic” and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Mr. Jacob S. Haas was not a physician. He was a Whig Party hack that was given the political patronage job of coroner for which he was completely unqualified. Haas was a liquor supplier and a victualler, which was traditionally a person who supplies food, beverages and other provisions for the crew of a vessel at sea. He was relieved later in the year of his coroner job because of supposed ill-health. (1)

According to the 1847 Philadelphia African American Census, Ms. Ginn was self-employed as a laundress who also did ironing. The highly acclaimed historian of African American History, Carter Woodson observed, “Without a doubt, many a Negro family in the free states would have been reduced to utter destitution had it not been for the labor of the mother as a washwoman.”(1) In the year that Ms. Ginn died, there were 4,249 Black women employed in Philadelphia. Out of that number, there were 1,970 who reported to census takers that they earned a living by taking in washing and/or ironing. (2)

The 1847 Census shows that Ms. Ginn was a single woman, likely a widow (3), and resided with a woman who was over 50 years of age. The census taker reported that this woman was “intemperate.” The two women received some sort of public aid, like firewood. Ms. Ginn attended church services, probably Bethel A.M.E., and was a member of a beneficial society that, presumably, paid for her funeral expenses.

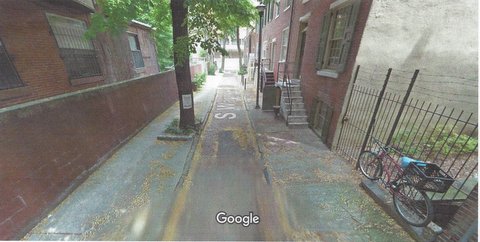

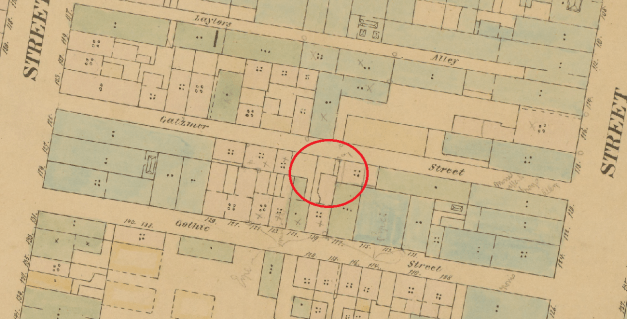

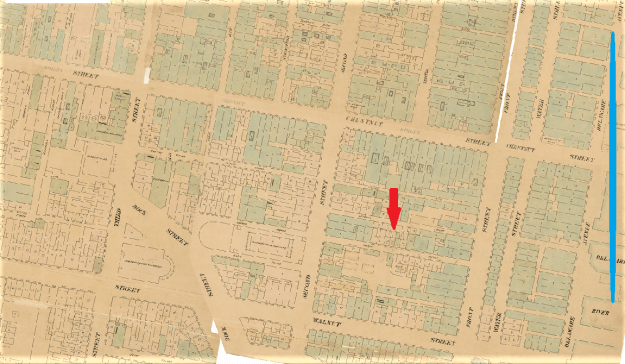

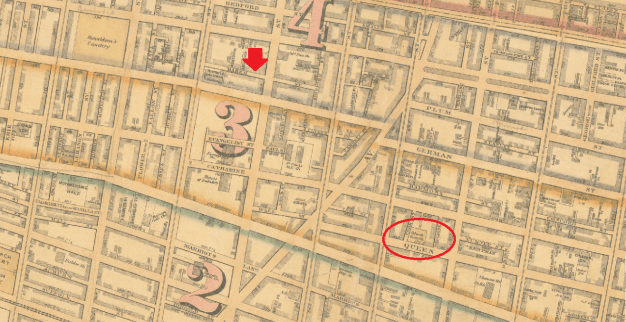

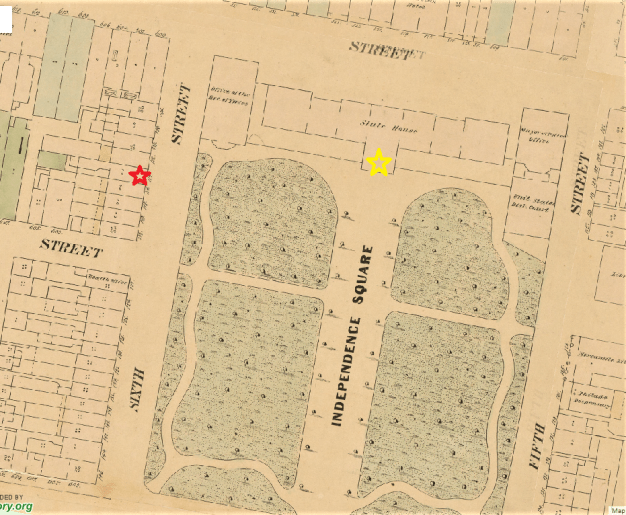

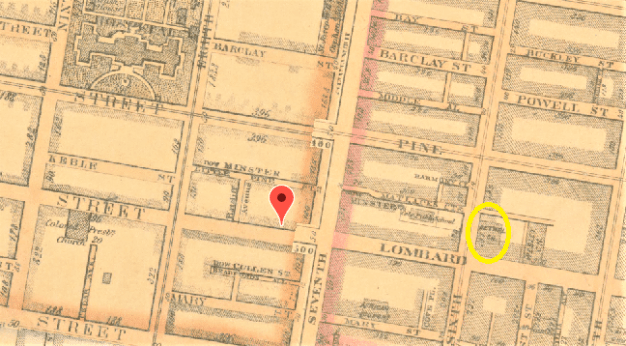

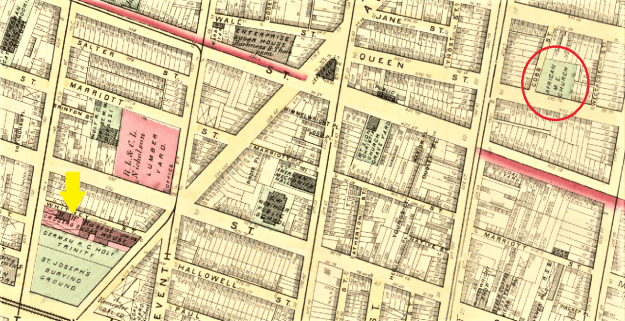

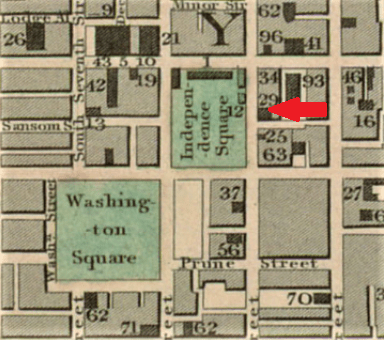

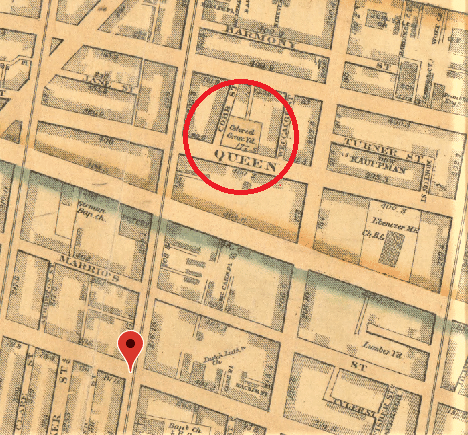

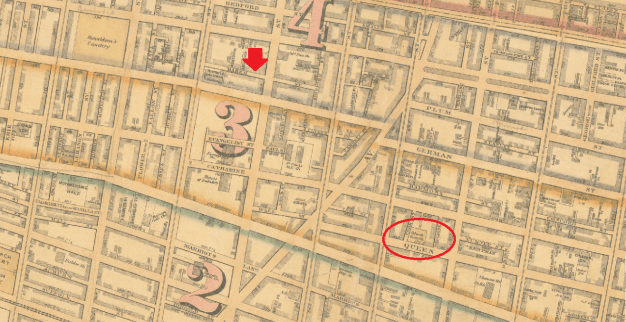

The red arrow on the above map illustrates the location of Ms. Ginn’s home on Baker Street, now known as Pemberton Street. The red circle indicates the location of the Bethel Burying Ground.

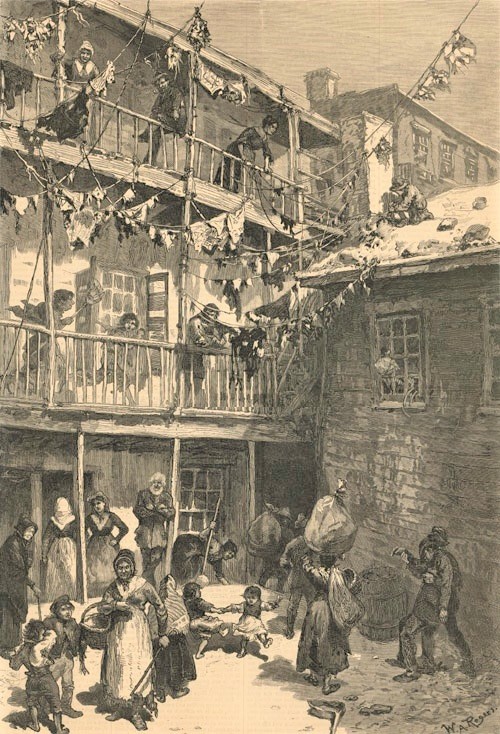

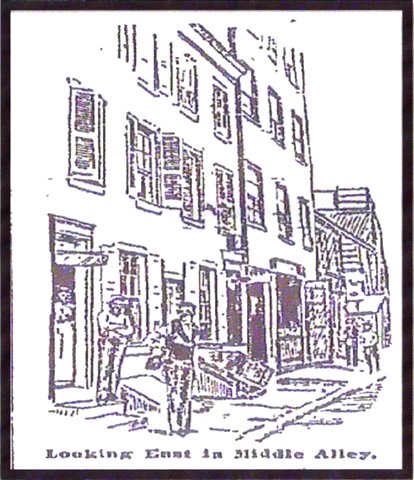

Ms. Ginn resided on Baker Street in South Philadelphia. She lived in a shack, that probably had been a horse stable or pigpen, located behind a shanty that faced Baker Street – hell on earth. This two-block long thoroughfare was cogged with “mud and filth” and was the epicenter in the county for deadly contagious diseases and deaths from poisonous alcohol. The numbers are absolutely stunning. In October of 1847, nine deaths were reported from alcohol, exposure, and neglect. In addition, there were six deaths from Typhus and Typhoid Fever. Incredibly, for the first ten months in 1847, there were a total of 132 deaths on Baker Street, including 68 children on this two-block hell hole. No one chooses to live like this. (4)

In November of 1847, the Philadelphia Board of Health started moving people out of their homes on Baker Street and boarding up the structures. They left the sick people in their homes because they didn’t want them to contaminant others. It was inconceivable that they left two Black women in their shanty who were suffering from fever but had “a fair prospect of recovery.” Could that have been Ms. Ginn and her roommate? (5)

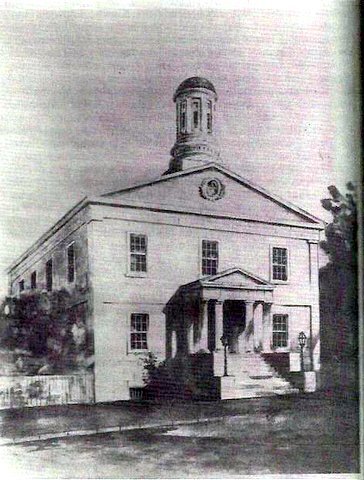

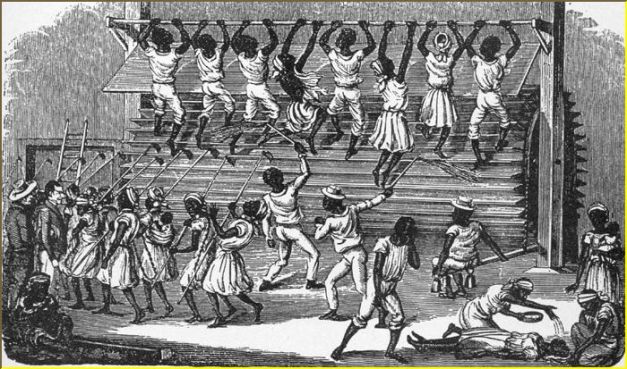

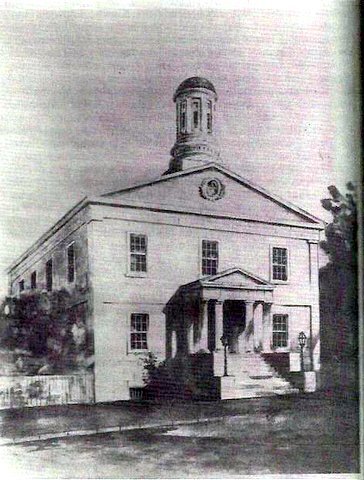

Moyamensing Hall where Nelson Barrington ran for protection.

In 1846, Ms. Ginn may have been one of the one hundred “wretched creatures,” mostly Black women, avenging a Black woman who was a victim of horrible spousal abuse. Nelson Barrington, a Black man, sold his wife and baby to a fugitive slave catcher from Delaware. The mother and child were put into Moyamensing jail, awaiting a hearing. A group of enraged Black women attacked Barrington in his home on Baker Street, very near Ms. Ginn’s home. They attacked with stones and other weapons with the intent of killing him. Barrington escaped and ran to a local municipal building, Moyamensing Hall, where the constables protected him. The crowd surrounded the Hall for a day until they were dispersed. They were no further newspaper accounts of the abuse victim. (6)

Jane Ginn died on a clear, warm winter day in late January where the temperature at sunrise was 42° and rose to 58° by late afternoon. Ms. Ginn was buried at Bethel Burying Ground.

NOTES

(1) John S. Haas . . . Philadelphia Inquirer, 25 June 1849, p. 1.

(2) The Negro Wage Earner by Lorenzo Garner and Carter Woodson, p. 4.

(3) Deaths on Baker Street . . . Public Ledger, 8 Nov 1847, p.2.

(4) Ibid.

(5) Ibid.

(6) 100 Black women . . . Sun, 25 April 1846, p. 2.