Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church

All posts tagged Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church

Tilman* Darrach, 48 years old, died this date, August 14th, in 1848 due to “Hemorrhage of the Lungs” and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. I could find no other information on Mr. Darrach. Interestingly, he died at the country home of wealthy Quaker industrialist John P. Wetherill near Phoenixville in Delaware County, Pennsylvania. The Wetherill home in the city was on 13th Street between Cherry and Arch Streets. It may be that Mr. Darrach was employed by the Wetherills and suffering from a terminal illness was allowed to spend his last days outside the polluted city. Hopefully, further research will uncover more details.

*I have chosen to go with the spelling of the first name as it appears on the Cemetery Return written by the Bethel Church sexton. See below –

** Free Quakers

Twenty-three-year-old Josiah Durham drowned in the Delaware River on this date, August 12th, in 1841 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. While working on the steamboat “Ohio” Mr. Durham fell overboard in the dead of night and drown. The steamboat was an excursion vessel that was “one of the most beautiful boats on the river.” (Philadelphia Inquirer, May 3, 1833.) Mr. Durham lived in Prosperous Alley which ran south from Locust Street, above 11th Street.

James F.T. Rodney, 3 years old, died this date, August 5th, in 1849 of Hydrocephalus* and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. The child was the son of Ann Elizabeth Rodney, a single mother who had four other children in her care. The Rodney family lived in extreme poverty in a room in Madison’s Court which was in the rear of 7th and St. Mary’s Streets for which Ms. Rodney paid $2.50 a month. The neighborhood was one of the worst in the city but was affordable for a woman who took in washing for a living while raising 5 children. All the children attended school. It appears that James, before his death was enrolled in the Lombard Infant School. Their home was only two blocks from Bethel Church at 6th and Lombard where the family attended services. (1847 African American Census)

*Hydrocephalus is an abnormal increase in the amount of cerebrospinal fluid that circulates in the brain. this puts increased pressure on the brain that produces an enlarged head and may lead to brain damage. The condition is associated with spina bifida, viruses, bacteria and funguses. (A Biohistory of 19th-Century Afro-Americans, Lesley M. Rankin-Hill)

The Philadelphia Tribune, 8/31/2015 – Michael Coard

Exactly two years ago this week, during the end of July 2013, a team of archeologists from the URS Corp. began breaking ground at the Weccacoe Playground after receiving scholarly evidence about a burial site there. And the rest, as they say, is history.

But before discussing that history, I must ask a few questions: What if 5,000 Italian or Irish or Jewish or Polish men, women, and children from one of the most pivotal periods of American history were buried in a cemetery in Philadelphia? Do you think there would be a city landmark or a state monument or a national treasure to honor it? Absolutely. But what if, instead, there were 5,000 African descendants buried in it? There would be no landmark, no monument, and no treasure. Quite the contrary, it would be a forgotten trash dump morphed into a city playground. That’s exactly what happened — and is still happening in 2015 — to a former Black church cemetery.

The Sixth and Lombard site of Mother Bethel AME was bought by Bishop Richard Allen and other trustees in 1791. They began services there three years later. In 1810, they purchased land at Queen and Lawrence (near Fifth and Catharine) and used it until 1864 as a private cemetery, known as Bethel Burying Ground. They were compelled to do so since Philadelphia’s public cemeteries would not accept Blacks. Things proceeded well until the church began to struggle financially and had to take bold steps to avoid foreclosure. Accordingly, the trustees in 1869 allowed unused portions of the cemetery grounds to be rented in a 10-year lease for wagon storage to Barnabas Bartol, a white man who operated a sugar refinery. There was an explicit condition in the lease mandating that those “who are interred… are to be allowed to remain there undisturbed.”

Despite that, as reported by a local newspaper in 1872, the refinery (as well as other white businesses) constantly “dumps rubbish… over the graves.” This caused the cemetery to deteriorate to such an extent that it could no longer function as intended. Therefore, it was sold in 1889 to the white city government that ignored it for a few more years before converting it into a city garden, beginning with the planting of saplings in 1901 and attaching a city playground to that garden around 1908. The Department of Recreation took responsibility of the park, known as Weccacoe, in 1910.

The remains of more than 5,000 Black men, women, boys, and girls are still there. Previously included there was Richard Allen’s wife, abolitionist Sarah Bass Allen, and still included there is the family of Octavius Catto’s fiancé, civil rights pioneer Caroline LaCount. And so is Ignatius Beck. He was a free Black man who, like Solomon Northup of “Twelve Years a Slave,” was tricked, forced and sold into slavery. While enslaved, he helped construct the U.S. Capitol in 1789 and later became the chairman of the Free Produce Society of Philadelphia, which spearheaded boycotts against anything made by slave labor. Black Civil War veterans are also buried there. The names and brief biographies of nearly 2,400 of these Black men, women, and children are presently known, and research is ongoing regarding the others. Those currently known include, alphabetically, Elizabeth Abbot, who died of “tuberculosis” at age 22 in 1825, through Ann Zittman, who died of “lung disease” at age 32 in 1848. Chronologically, in terms of birth, they include Parker, whose first name and gender were not recorded, who was “stillborn” in 1812, through Phillis Garne, who died at 113 of “old age” in 1823.

The problem during the past few years is that the white neighborhood associations didn’t give a damn about this historic Black site and the mayor’s office was dragging its feet. In fact, a project called “Green 2015,” a community and municipal plan from 2013 to turn 500 acres of underused land into green space, was ready to commence full speed ahead. And Weccacoe was selected as the park to become the plan’s first project, with “green renovation” grants from local and state government totaling $535,000. But that project called for playground renovations requiring excavations for sewer, water and electrical lines and the planting of trees. So what about the Black people buried there? I say to hell with “Green 2015!” We need “Black 2015!” And we need it to finally memorialize the literally buried truth about an undeniably sacred site.

Although the Philadelphia Historical Commission and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission have issued favorable rulings regarding the site, the more than 5,000 historic remains are still under the trash dump and city playground with no official memorialization by the mayor’s office, despite repeated demands by activists.

This article could not have been written if it were not for the dogged persistence and meticulous research of historian Terry Buckalew. He says he stumbled across this historic find while researching the life of local civil/voting rights giant Octavius Catto. You can read Buckalew’s enlightening information by logging onto https://bethelburyinggroundproject.com/. Two years ago, he profoundly described the burial site as “Philadelphia’s equivalent of Arlington National Cemetery in terms of its historic significance.” This week, he unequivocally proclaims that “Bethel Burying Ground is the greatest repository of African-American history in Philadelphia. The more than 5,000 buried on Queen Street were courageous pioneers in the most racist northern city in 19th century America. They were oppressed, persecuted, assaulted, buried, sold, and forgotten. Yet, research has shown despite all this, these women and men were able to weave a rich tapestry of family and community. The preservation of their remains and of their stories demand our best efforts.” Oh, by the way, did I mention that Buckalew is white?

The galvanizing activism during the past few years could not have happened if it were not for the effective mobilization and relentless demands of Joseph Certaine, a former managing director and a U.S. Colored Troops/Buffalo Soldier reenactor. He made it clear this week that “Although a lot of progress has been made toward the designation of Bethel Burying Ground as a national historic site, it is of paramount importance that Philadelphia taxpayers understand that the site is owned by the citizens of Philadelphia. The city of Philadelphia should relocate the public toilets and meeting room from atop these historic resting places to another location within the footprint of the recreation center. The city must stabilize and secure the Burial Ground within its boundary markers and ensure its future treatment as a publicly owned historic site.”

If you’d like to assist Buckalew and Certaine in ending this desecration, please contact Avenging The Ancestors Coalition at (215) 552-8751 and ask about its “Not Over Our Dead Bodies” committee.

Charles Jones, 30, died this date, July 30th, in 1813 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. He died after being crushed under the wheels of a cart. The City Coroner ruled the death an accident. Mr. Jones was occupied as a woodsawyer and lived at 328 S. 6th Street only two blocks from Bethel Church.

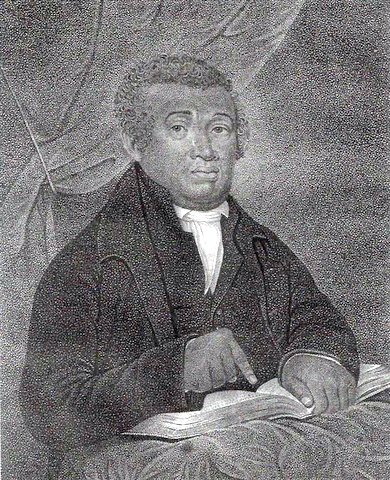

A portrait of Rev. Richard Allen painted in 1813 the year of Mr. Jones’ death.

July 29, 1794: Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania was dedicated. Mother Bethel was founded by Richard Allen and organized by African American members of St. George’s Methodist Church who walked out due to racial segregation in their worship services. The current structure was built in 1890 and is the oldest church property in the United States continuously owned by African Americans. Bishop Allen, his wife Sarah, and Bishop Morris Brown are entombed in the current structure. The church today has approximately 700 members. Mother Bethel was designated a National Historic Landmark March 16, 1972, and a Pennsylvania Historical Marker was dedicated in 1991. http://thewright.org/explore/blog/entry/today-in-black-history-07292015

Margaret Jerrido, archivist for the Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church, looks at an image of Richard Allen. APRIL SAUL / Staff Photographer. Philadelphia Inquirer 2/20/13

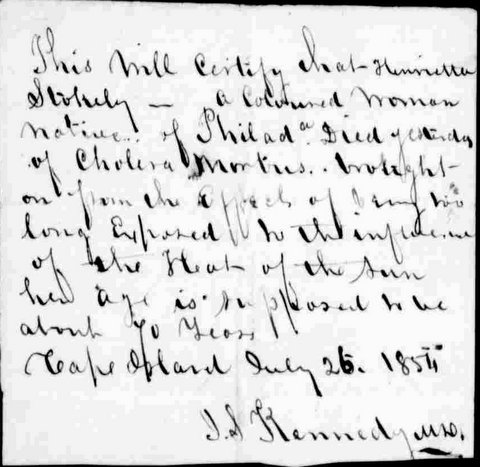

Seventy-year-old Henrietta Stokely died this date, July 26th, in 1854 of Cholera and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Ms. Stokely was vacationing at Cape Island, NJ (now Cape May)and contracted Cholera. The doctor who wrote the death certificate believed Ms. Stokely caught the disease from prolonged exposure to the “Heat of the Sun.” Even for 1854 this was quackery. Mainstream medicine at the time believed the disease was caused by miasma or exposure to an unpleasant smell or vapor. Perhaps similar to the smell of a decaying corpse or rotting fruits or vegetables. It wasn’t until 1884-85 that science was able to identify the Cholera bacteria as the source of the deadly illness. The disease was commonly brought on by drinking water contaminated by the feces from a person who already had the Cholera bacteria. The bacteria could also come from raw or undercooked fish and seafood caught in waters polluted with sewerage. The crippling symptoms of Cholera came quickly, first diarrhea and vomiting, abdominal cramps, shock, then death.

Harriet Tubman worked as a cook in Cape May in 1852, earning money to help runaway bondsmen. She developed fugitive slave routes in Salem, Cumberland and Cape May counties, including obscure Indian trails. – See more at http://www.capemay.com/blog/2001/09/cape-mays-role-in-history-pathway-to-freedom/#sthash.97naePSS.dpuf.

Margaret Shorter, 55 years of age, died this date, July 24th in 1849 after suffering a stroke. Sadly, little else is known about Ms. Shorter. She lived on Cobb Street which is across the street from Bethel Burying Ground. It is very likely she lived at #3 Cobb Street and was a live-in domestic for the African American Brister/Parker family. For further reading on this family, I suggest going to http://www.archives.upenn.edu/people/1800s/brister_james.html.

Robert Howard, 63 years old, died this date, July 21st, in 1849 of Cholera and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. From the records of the 1847 African American Census, it appears that Mr. Howard lived with his spouse, several children and possibly his or her’s parents and/or grandparents. There was one female in the family over 100 years old. The Howard family lived in Acorn Alley (now Schell St.) which ran between 8th and 9th streets and Bainbridge and Fitzwater streets in south Philadelphia. He worked as a cook and Ms. Howard took in washing to add to their income. The Howards were neighbors of the Reverend John Boggs an AME minister of some prominence. Rev. Boggs died a little over a year before Mr. Howard.

Tragically the city was being ravished by Cholera in the summer of 1849. Mr. Howard was one of 196 individuals that died in the city and county of Philadelphia the same week as he did. Twenty-eight people a day were dying from the disease. (Public Ledger, 25 July 1849, p. 2.)