Bethel Burying Ground

All posts tagged Bethel Burying Ground

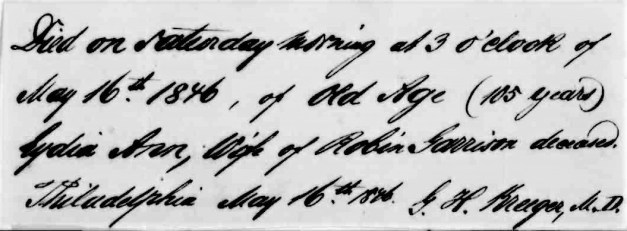

One-hundred five-year-old Lydia Ann Garrison died this date, May 16th, in 1846 of “old age” and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. She had led a long life without leaving anything but a small documented trail. Ms. Garrison or her spouse Robin, who predeceased her, are not recorded in any local or federal censuses. They were not reported in any city directories that I could locate.

According to the Pennsylvania Abolition Act of 1780, if you were Black and lived in Pennsylvania before 1780, you remained enslaved. Ms. Garrison was already at least 40 years of age at that time. According to the law, your children would be enslaved until the age of twenty-eight. Therefore, it was only after 1810 that a substantial community of free Blacks gathered in Philadelphia.

Out of surviving records, Ms. Garrison was not the oldest person buried at Bethel Burying Ground. There were two women interred who were older – one a 110-year-old and another 113 years of age.

Surviving city death certificates do not show any family members of Ms. Garrison buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Lydia Ann Garrison was interred on a warm day (68°) in May. It can be assumed she was of strong character and spirit.

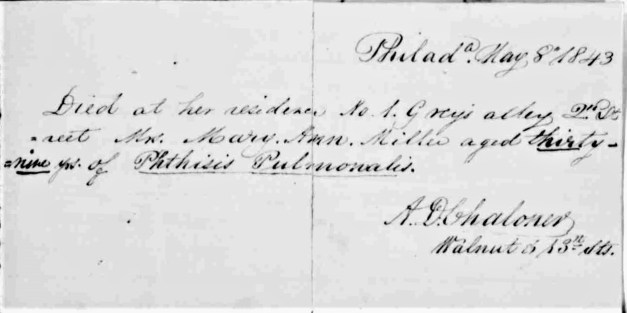

Forty-three-year-old Mary Ann Miller died this date, May 8th in 1843, of Tuberculosis and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Ms. Miller was a dressmaker, according to the 1838 “Register of the Trades of Colored People in the City of Philadelphia and the Districts.” She worked out of her home at the corner of #1 Gray’s Alley and 2nd Street, near the Delaware River docks and the center of the city’s import/export business.

The 1837 Philadelphia African American Census reported that eighty-two Black women made their living by dressmaking at the artisan level.

Gray’s Alley was a small narrow alleyway that contained twenty-five African American families totaling seventy-three individuals, according to the 1847 Philadelphia African American Census. The crowded underventilated lodgings were the perfect environment for the disease that killed Mary Ann Miller. The male members of the families on Gray’s Alley were laborers, usually working as porters at the Delaware docks, and the female family members were laundresses or domestics who worked in the homes of the wealthy merchants nearby. Families would live in one room in the two and three-storied brick homes that were built before the Revolution. The rooms were commonly 10’x10′ for which the rent was around $1 – $2 a week.

Ms. Miller would have lived through the thirteen years of mob violence against Philadelphia’s people of color prior to her death. In 1842, the year before she died, there was a three-day riot in August that saw white mobs loot and burn Black homes, churches and public buildings. Black men and women were assaulted and forced to flee the city. There was never an accurate accounting of murdered African Americans. No whites were held significantly accountable. The mayor criticized the African Americans of the city for being provocative by demanding their civil rights.

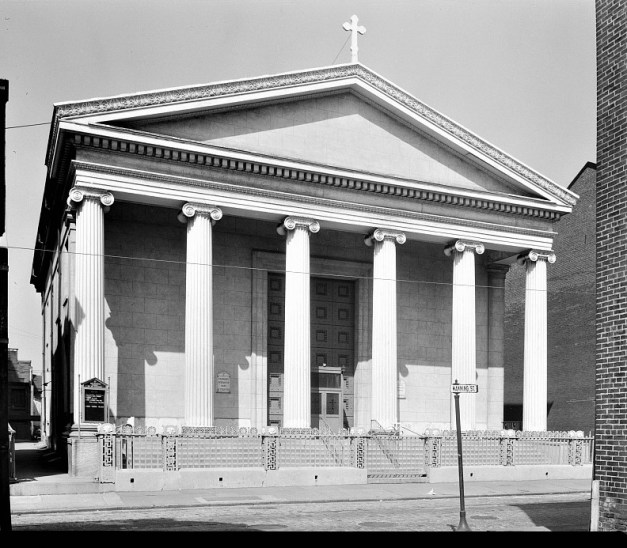

Fifty-year-old Sarah Medad Westwood died this date, April 5th, in 1853 of a stroke (Apoplexy) and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Her spouse, Keeling Westwood, worked as a confectioner earning $30 a month. A confectioner was a person selling and/or making candy or other sweets. Ms. Westwood was employed as a “baker,” according to the 1847 Philadelphia African American Census. It appears that one of the older children worked in a store for $4 a week which was a good wage. It appears from that Census that the Westwoods had four children, two of whom were younger than two-years of age and two of whom were between two to fifteen years of age. Three were attending the Shiloh Baptist Church Infant School at South and Clifton Streets, now far from the Westwood home in Osborn’s Court, near 8th and Spruce. The photograph below is what the church infant school looks like currently. It is now an African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Ms. Westwood was born in Accomack County, Virginia in 1803 to Irving and Betty Medad. The 1820 Federal Census lists Ms. Betty Medad as a single free Black woman. Mr. Medad is not listed in the Census. It appears he was deceased prior to 1820. Accomack County, Virginia was a rarity in the Commonwealth of Virginia. Being located on the Eastern Shore, it did not have an agriculture economy that required the amount of slave labor that the plantations in the rest of the state required. In addition, the spread of Methodism and the influence of Quakerism in the county, plus the powerful personalities of several large landowners, created a unique social environment that fostered the emancipation of enslaved Black men and women. (Race and Liberty in the New Nation, pp. 61-62 by Eva Sheppard Wolf)

The Westwoods lived on a narrow back alley in one room for which they paid $2-$4 a week. Osborn’s Court was typical for the era with the water spigot and privy outdoors. Street cleaning was infrequent, if at all, and, consequently, trash, garbage, ash and animal waste would form piles that would block gutters and force rainwater back in the cellars. Interestingly, Osborn’s Court had a long history of one of the more notorious houses of prostitution in that area of the city. There are numerous newspaper reports over the era of brawls between the ladies and their clients. The more violent encounters were between the ladies themselves. All this in the shadow of a large Protestant Church!

Osborn’s Court ran behind St. Andrew’s Protestant Episcopal Church at 250 S. 8th Street.

Thirty-five-year-old Sarah Golden died this date, April 30th, in 1853 of Tuberculosis and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. She worked as a laundress earning $50 a year, according to the 1847 Philadelphia African American Census. Fifty dollars in the year 1847 is equivalent in purchasing power to $1,506.80 in 2018.

Ms. Golden was married to Samuel Golden who was employed as a waiter and, at one point, worked part-time in a stove store. The death of Ms. Golden left three children motherless – Joseph (16 y/o), Emeline (8) and Isabella (5), according to the 1850 Federal Census. The family moved a good deal. They lived in Atkinson Court, Smith’s Court and Hurst Street – all locations where the residents lived in extreme poverty and perfect environments for Tuberculosis to spread. The entire family likely would have lived in a 9’x9′ room for which they paid approximately $5 a month.

Mr. and Ms. Golden sent their children to local schools that were established by private institutions to educate Black children and, according to the 1847 Census, three members of the family regularly attended church services. A surviving Philadelphia Board of Health death certificate reports that Sarah’s son Joseph died at 25 years of age of a stroke while employed as a “mariner.”

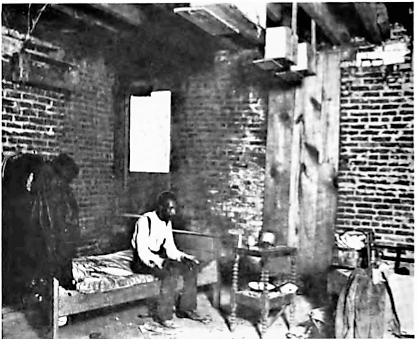

An elderly Black man dying of Consumption (Tuberculosis ) living in the cellar of a tenement. “Neglected Neighborhoods,” p. 279. Chas. F. Weeler is the author.

One-year-old Lafillia Harrison died this date, April 28th, in 1840 of Convulsions and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Her parents, James and Lafillia Harrison, lived on Carpenter Street between 8th and 9th Streets in South Philadelphia. The 1847 Philadelphia African American Census reports Ms. Harrison’s occupation as “nurse” and Mr. Harrison as “in service,” most likely as a butler or a coach driver. There also is another female in the household who is reported to be between 15 and 50 years of age and employed as a seamstress.

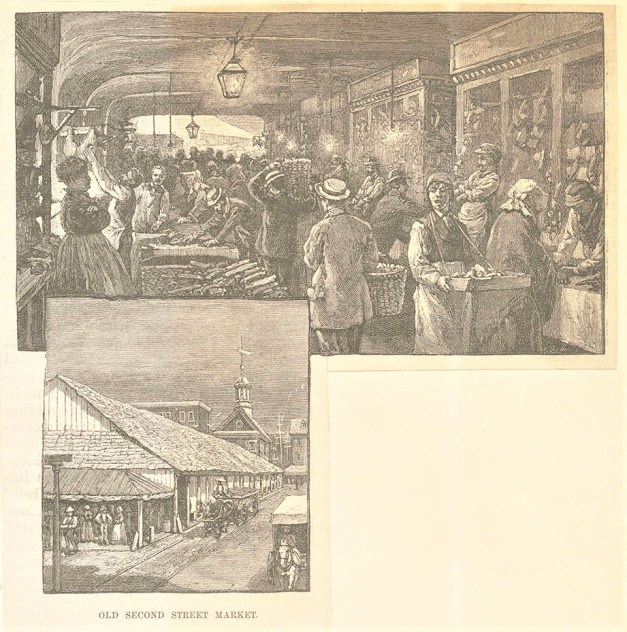

The Harrisons’ Carpenter Street address is currently only a block away from what is now known as the “Italian Market.” The name for the market was coined in the early 1970s for an area of south Philadelphia featuring numerous grocery shops, cafes, restaurants, bakeries, cheese shops, and butcher shops. In 1840, the Harrisons would have shopped for food and dry goods at the Eleventh Street Market at 11th Street and Moyamensing Avenue, about a mile away to the west. The other close market would have been at 2nd and Pine Street, again about a mile away. The Harrisons would not have been able to use public transportation to go to the markets because of the color of their skin.

Above are two views of the South Street Market where the Harrisons may have frequented. The Moyamensing Market would have been very similar.

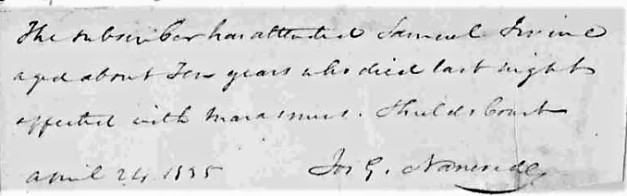

Ten-year-old Samuel Irvine died this date, April 23rd, in 1835 of Marasmus and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. An archaic term, ‘Marasmus’ stood for a variety of malnutrition, wasting and starvation illnesses. The condition has been characterized as a disease of the “extremely poor.” Often the infant or child was getting too many carbohydrates (cheaper) and little if any protein (more expensive).

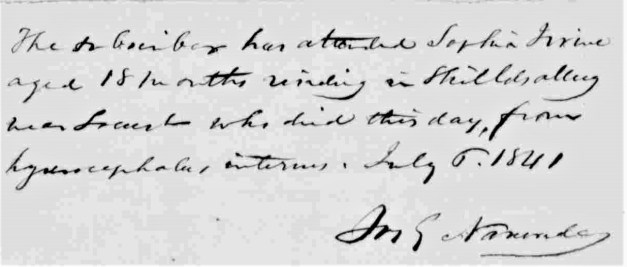

The identity of young Samuel’s parents is a mystery at present. They do not appear in any city directories nor in local or federal censuses of the era. The family did lose another child, eighteen-month-old Sophia, due to Hydrocephalus, on July 6, 1841. The Irvines lived in Shield’s Alley at the time when both children passed away, according to their death certificates. It appears that the adults did not want their existence to be public knowledge. Perhaps one or both were escapees from enslavement. Slaves catchers roamed the cities of the North looking for liberated Black men and women.

Another interesting circumstance is that the children’s death certificates were both signed by the same physician whose first language was French. There is an indication that he may have practiced medicine in Haiti at one time.

This is the death certificate of Sophia Irvine who very likely was the sibling of young Samuel. They probably rest in the same grave. Dr. Joseph G. Narende signed both certificates.

Shield’s Alley was a dead end backstreet, only ten feet wide, lined with two-story wood frame buildings, split down the middle by grimy cobblestones. Located at the corner of 9th and Locust Streets in center city Philadephia, the Irvine home would have been a room, maybe 12’X12′, with no running water or indoor toilet, both of which would have been available in the backyard of the building. For this, according to the 1847 Philadelphia African American Census, they would have paid from $2-$3 a month. The average weekly salary for an African American laborer was $3-$4 a week when they were able to find work.

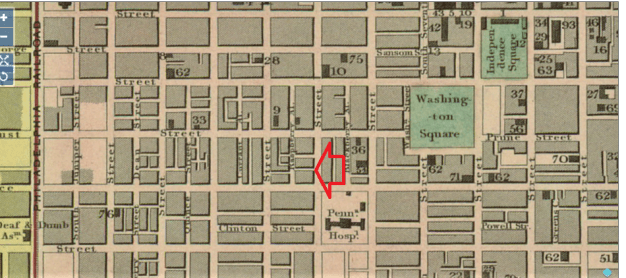

Shield’s Alley (red arrow) was later renamed Aurora Street. It no longer exists and is currently the location of a parking garage for Jefferson University Hospital.

And there is this union of trial and mercy in the removal of a young child. We cannot rebel against God for taking them to heaven, and yet we cannot but mourn over our loss; what can we do . . . (Rev. William Henry Lewis – 1857)

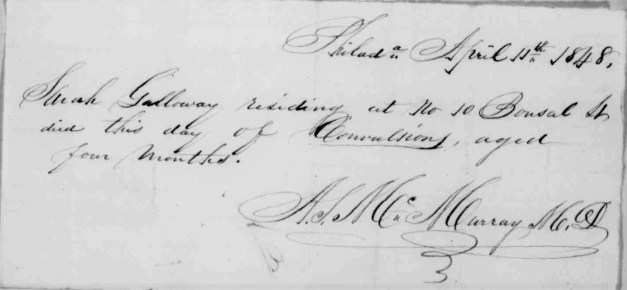

Four-month-old Sarah Galloway died this date, April 11th, in 1848 of Convulsions and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Sarah was the daughter of Benjamin (~47 y/o) and Rebecca (~43) Galloway. They had three other children Matilda (~10), Mary (~8) and Isabella (~5). The family lost another daughter, 6-year-old Rebecca, on December 1, 1847. She died of a brain fever, possibly Meningitis and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground.

There was also a twenty-four-year-old male named James Galloway in the household whose relationship to the family is unknown. He was employed as a waiter in 1847 and a boxman in 1850, according to census records.

The Galloway family rented a room or two at 10 Bonsall Street, later known as Rodman Street. They lived on one of the floors of a three-story house with stairs up in a piazza or veranda, similar to the photo below. The indoor hallways would connect to the outdoor landings and the flight of stairs to the next floor.

There was no indoor water service in the house on Bonsall. Water was obtained from the hydrant (spigot) in the backyard of the house near the privies. The water for drinking, cooking, laundry, and washing had to be carried upstairs.

A young woman, “Trilby,” standing next to an outdoor hydrant.

Ms. Galloway worked as a laundress and would have been very familiar with the backyard water supply. Mr. Galloway was employed as a silk dryer, a very skilled profession, rare for an African American to hold. The work of a silk dryer was labor-intensive and one of precision. The dryer’s duties included cleaning the raw silk, bleaching it, adding chemicals to fix the color, dyeing, and drying. To clean raw silk, the dryer hung the silk on a long pole and immersed them in a large vat of boiling soapy water. He or she then would rinse the silk clean in a running river. The poles would be carried back to the factory and the process would be repeated and the desired hue achieved. The poles then would be carried back down to the river to be rinsed for the second time and, once again, carried back to the factory and hung up to dry.

Benjamin and Rebecca Galloway lived long lives with their married children and grandchildren residing with them in a house on Lombard Street, according to the 1870 Federal Census. Benjamin died on February 2, 1880, at the age of seventy-eight of Stomach Cancer. He was still employed in the silk manufacturing and cleaning business. Ms. Galloway was still alive at the time of her husband’s death. Her death certificate isn’t on file.

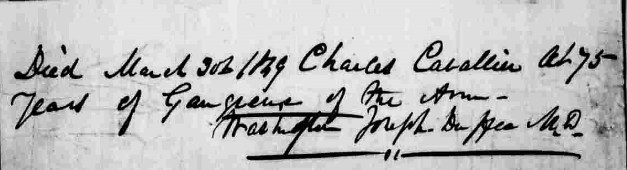

Seventy-five-year-old Charles Cavalier* died this date, March 30th, in 1849 due to gangrene of an arm and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. He raised pigs in the rural “Neck” section of far south Philadelphia. His spouse, who is unnamed, worked as a domestic. Both were not native to Pennsylvania, according to the 1847 Philadelphia African American Census.

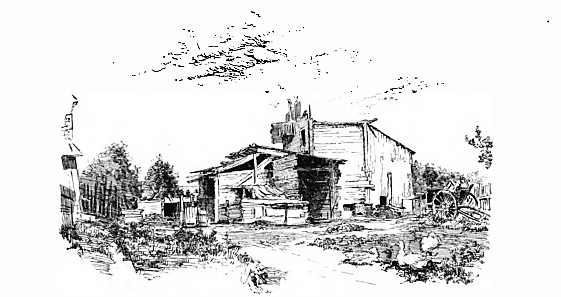

The “Neck” was a crisscrossed mishmash of swamps, meadows, dikes, and canals. It was well known for its cabbages, thousands of pigs, packs of dogs, game birds, eccentric residents and especially for its smell. Situated in these moors were several hamlets that were little more than a cluster of shanties that bore names like Frogtown and Martinsville. The Cavaliers lived in such a pocket with a number of Black families. However, the vast majority of the residents of the “Neck” was Irish with a few Dutch families scattered about.

A small farm in the “Neck.”

A Black man working in the “Neck.”

The dozens of creeks and canals in the “Neck” were a long recognized health hazard by the city’s Board of Health. They had become the receptacle of diseased refuse that included dead animals, while its canals’ banks were lined with outhouses, emptying their contents in the slow-moving sewer, and the waste from cows, pigs, and horses, dye houses, slaughterhouses, kitchens, and street-sewage. Also, it was not uncommon to see a corpse floating by on its way from the city to the Delaware River. It was a very difficult environment to keep a wound clean and was possibly the source of the infection that led to Mr. Cavilier’s cause of death.

Photograph by T. Buckalew

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

For a fuller story on the “Neck” please go to –

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924079637470;view=2up;seq=354

*The spelling of “Cavalier” on the death certificate with two Ls is incorrect. Census records and city directories have the spelling with one L.

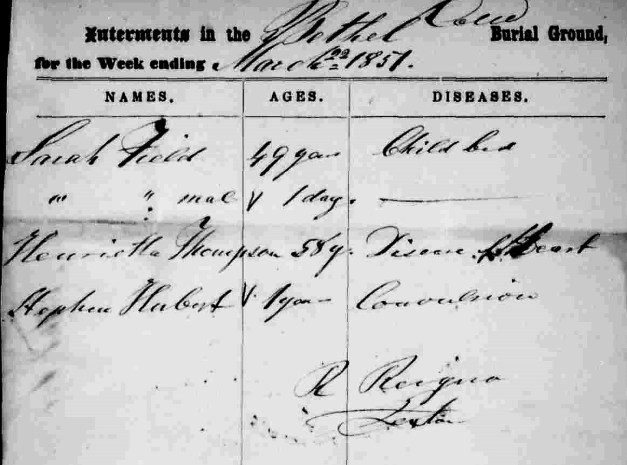

One-year-old Stephen Hubert died on or near March 23rd, in 1851 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. The cause of death is listed as convulsions. The death certificate signed by a physician has not survived. Above is the weekly summary signed by the Bethel Church sexton and manager of the cemetery.

One-year-old Stephen Hubert died on or near March 23rd, in 1851 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. The cause of death is listed as convulsions. The death certificate signed by a physician has not survived. Above is the weekly summary signed by the Bethel Church sexton and manager of the cemetery.

From existing documents, it appears the child was the son of Littleton* and Ann Hubert, 46 and 39 years old respectively. Tragically, Ms. Hubert died a year later of Tuberculosis. It also is likely the family had lost another child in January of 1847 due to “Fever.”

Littleton and Ann were native to Delaware, moving to Philadelphia sometime before 1837. By 1837, Mr. Hubert was a “well-to-do grocer” who, by 1847, was one of the “elite” of the African American community. He was a successful restaurateur, owning a popular “eating-saloon” on 6th Street above St. Mary’s Street, within sight of Bethel AME Church at 6th and Lombard Streets. In 1847, he reported the value of his real estate holdings at $190,000 and his personal property at $100,000 – both numbers are translated to current dollar values. Census records report that Ann Hubert worked in the family business.

Mr. Hubert, formerly enslaved, was very active in the community. In 1837, he was a delegate to the American Moral Reform Society along with successful Black businessmen and leaders of the community James Forten and Robert Purvis. Hubert was also a member of the Philadelphia Temperance Society. In 1841 he joined the call, with other Black leaders, for a revival of the National Convention Movement. He was a prominent member of an African American Masonic lodge and he likely assisted William Stills with hiding fugitives on the run from roaming slave hunters. Mr. Hubert was not shy with his money or time in providing support for captured fugitives.

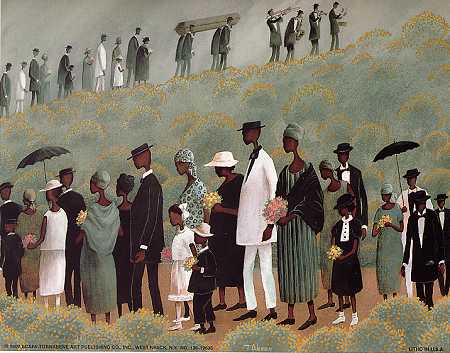

Well-to-do 19th century African American family

African-American men in Philadelphia were allowed to succeed in a few upscale professions during the antebellum era. Food service was one of them. Most of those who prepared and sold food ran modest operations—an oyster-cellar or a small eatery of some sort—but a handful of people, such as Littleton Hubert, James LeCount, Gil Ball and Thomas J. Dorsey had establishments that serviced both white and Black customers.

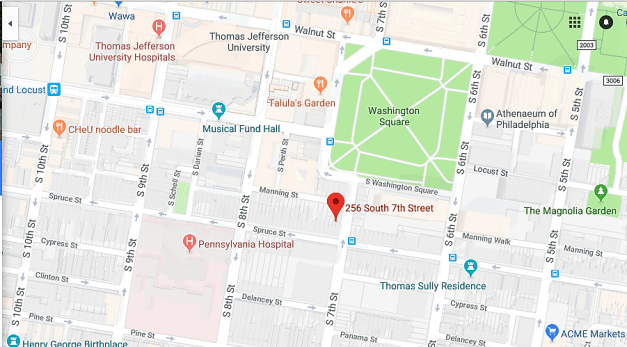

The Hubert family lived at 256 South 7th Street between Washington Square and Pennsylvania Hospital. All members of the family could read and write with the children being educated by African American educator Solomon Clarkson at his school near 6th and Lombard Streets.

Modern map of the area

- In one City Directory, Mr. Hubert’s first name is spelled “Lyttleton.”