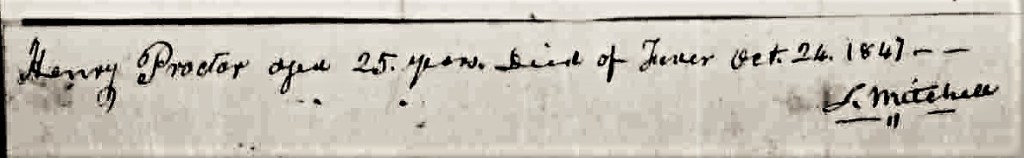

Twenty-five-year-old Henry Proctor died this date, October 26th, in 1847 of “Fever” and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. It appears that Dr. John Mitchell took little time seeking out Mr. Proctor’s cause of death. In reviewing Philadelphia Board of Health records for 1847, it appears that the citizens were being plagued by a serious outbreak of Scarlet Fever. Mr. Proctor may have succumbed to this bacterial disease that is usually seen in children. He may have contracted it from a child in his family.

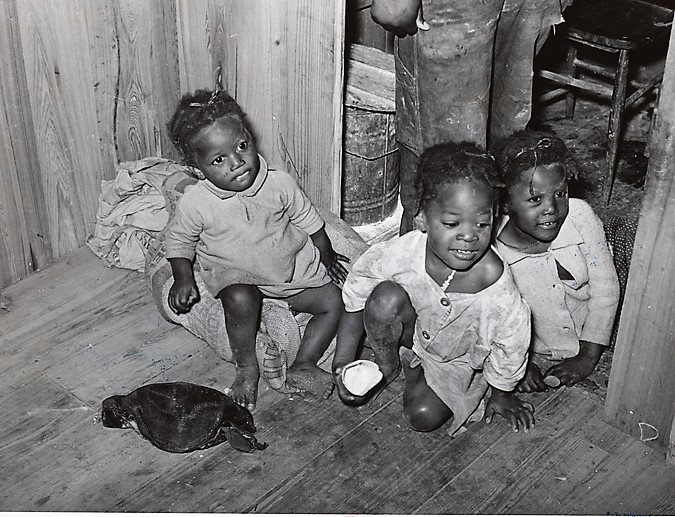

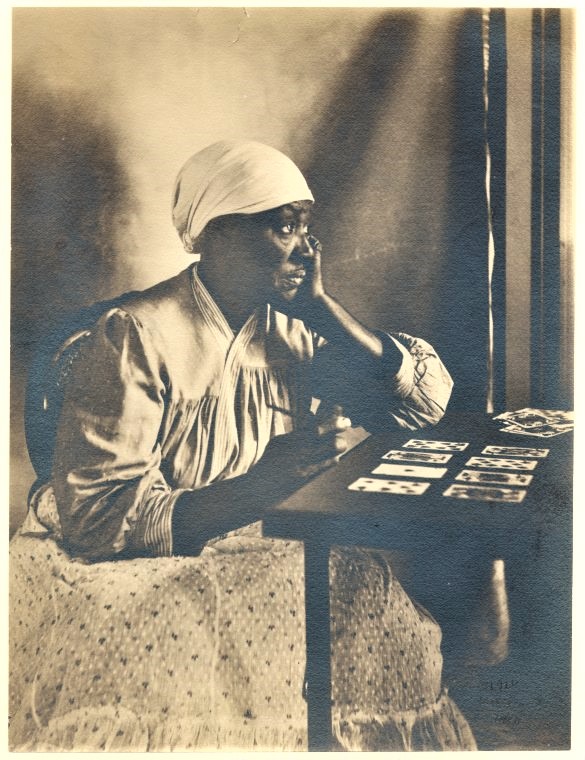

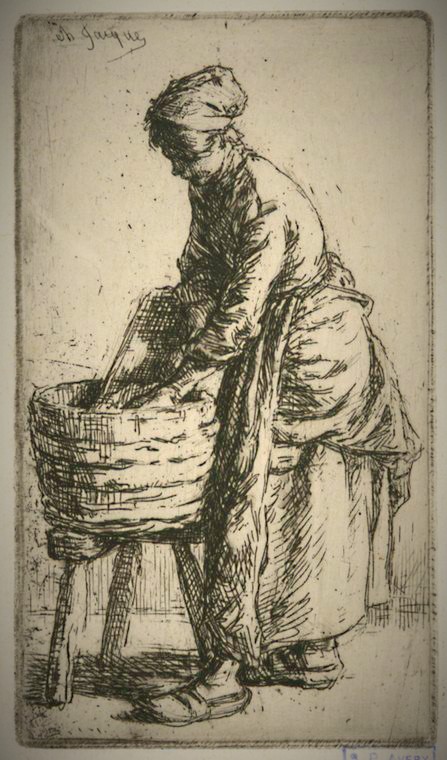

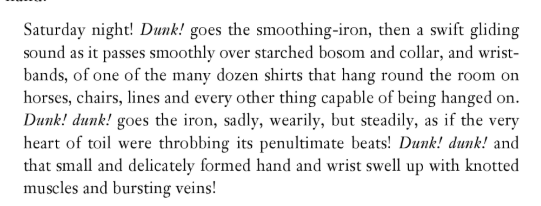

According to the 1847 Philadelphia African American Census, Mr. Proctor lived in Stevens’ Court with two children and four adult women. Three of the women served as “in-service” domestics and may have been staying at their employer’s home during the week. Mr. Proctor worked as a laborer earning $6 a week. The woman who stayed at home with the children was also employed as a laundress who also did ironing! For every dozen shirts finished, she would have made upwards of 10 cents. Everyone in the family was born in Pennsylvania.

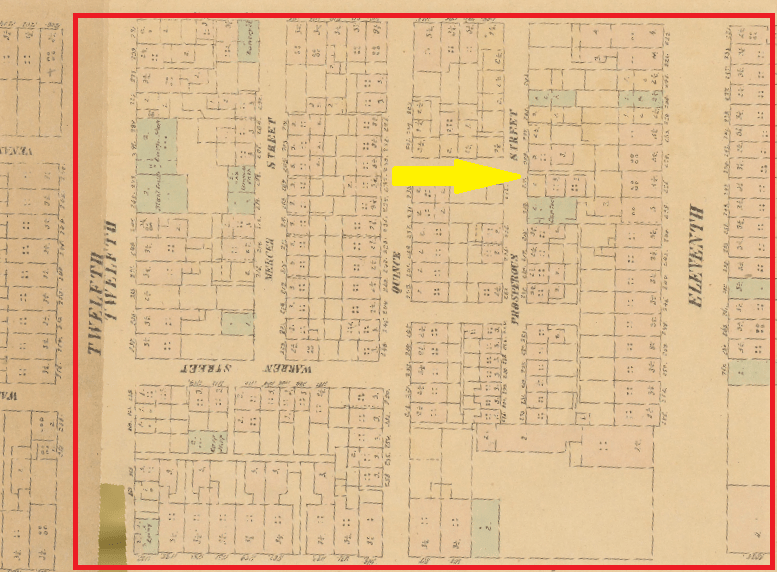

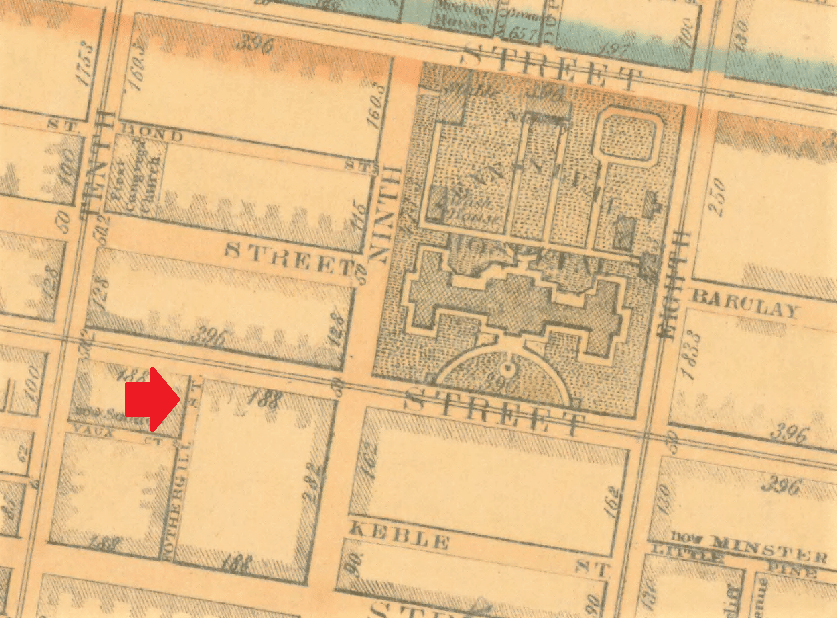

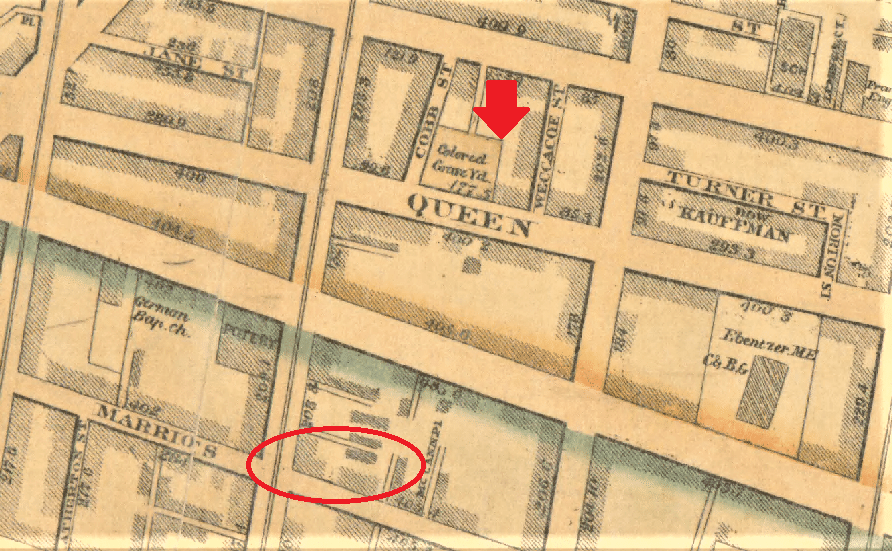

The Proctor family likely lived in two rooms for which they paid $2.50 a month, according to the 1847 Census. At the time of Mr. Proctor’s death, Stevens’ Court was home to 16 Black families with a total of 86 members. All of the women in these families worked as laundresses while the men worked as laborers. There were two men who reported their occupation as “seaman.”

Old Philadelphia was traditionally a mob town. Generations of white citizens daily roamed the city’s streets looking to beat down anyone of a different race, religion, or political party. The police force was small and afraid of the gangs. For many years, the policemen refused to wear their uniforms for fear of being identified and assaulted by gang members. The citizenry would not be surprised to hear that federal troops had to be used to quell a riot initiated by a white mob.

The residents of Stevens’ Court lived in a very dangerous neighborhood for African Americans. Blacks were denied access to public transportation which forced many to live near their place of employment. Some locations were worst then others. In this case, Stevens’ Court was only several blocks away from the home of the Moyamensing Hose Company (aka “The Rowdy Boys of Moyamensing”) and the “Killers” – their murderous enforcers. Their sole goal was to rid Philadelphia of Blacks and Protestants. To this end, no form of violence was ruled out. Guns, knives, clubs, cobblestones, and arson were all utilized. (1)

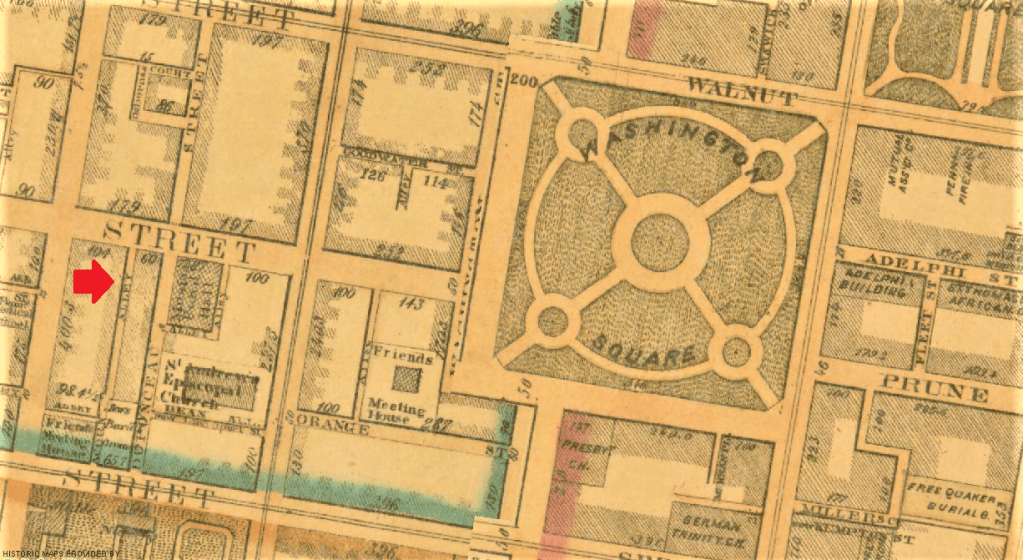

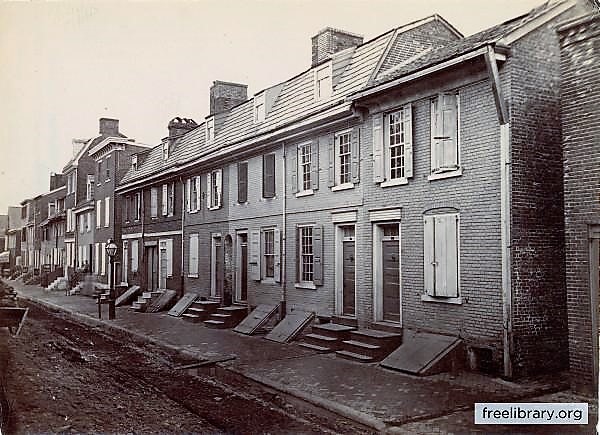

Many in Stevens’ Court likely remember the destruction of “Red Row” and feared the same might happen to them. In July of 1835, a Black man stabbed a white man with whom he was fighting on South 2nd Street. Also a Black man working as a butler assaulted his employer. The white gangs in the city used these incidents to mount rampages through the African American neighborhoods. “Red Row” was a block long row of nine wood frame houses located on Christian Street between 8th and 9th Streets. All were occupied by Black families. The origin of the term “Red Row” isn’t clear. It has been used as a disparaging term for a small community of African Americans or a neighborhood of poor whites.

On the night of July 27, 1835, a mob of 1,500 white men and boys broke into and destroyed the homes of Black families on Red Row. Most of the African American adults were able to grab their children and escape through their back doors into the alleys and backyards of their neighbors. However “several men were concealed in a chimney in one of these houses, a torch was applied to burn them out, and the house was quickly in flames.” All the houses on the row were destroyed by fire. All the furniture was destroyed and the families’ valuables and food were stolen. A Black women who had given birth four days before was able to successfully escape with her newborn. She had no where to go and hid in the grass of a vacant lot. (2)

A group of armed Black men were eventually able to engage in a running gun battle which killed and wounded approximately ten white men, according to newspaper reports. But the torture, beatings, and arson were accomplished. The Black men and women of Stevens’ Court lived with the memory of the savagery that could occur any minute of any day to them.

Mr. Proctor died on a day in late October in 1847 and was buried by his family, with dignity, at Bethel Burying Ground.

(1) Harry C. Silcox, Philadelphia Politics from the Bottom Up: The life of Irishman William McMullen, 1824-1901.

(2) Philadelphia Inquirer, 28 July 1835, p. 2.