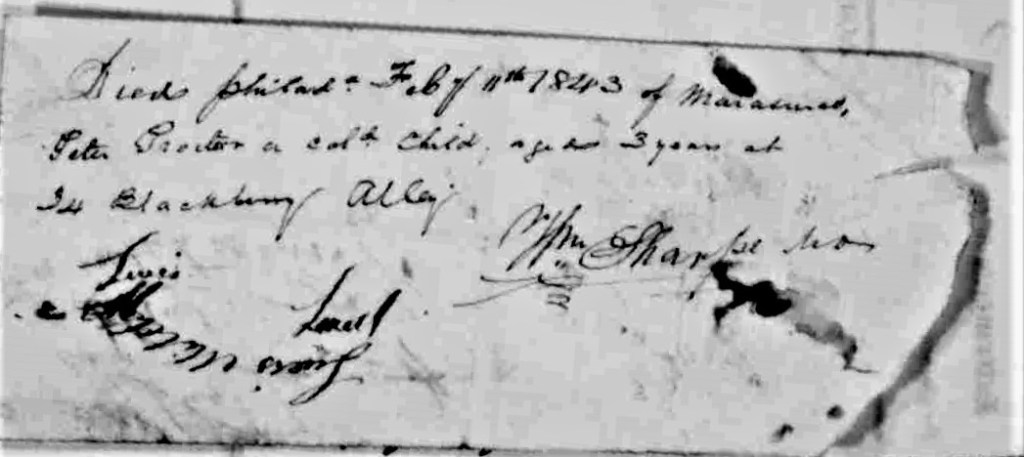

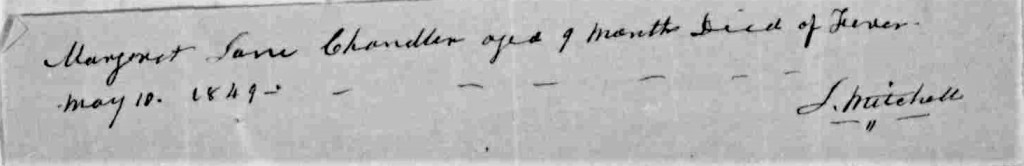

Thirty-five-year old Lavinia Chandler died this date May 6th, in 1849, of “Fever” and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Her daughter nine-month-old Margaret Jane died four days later on May 10th, presumably of the same illness. The baby was buried with her mother at Bethel Burying Ground. The Philadelphia Board of Health records for 1849 show a substantial number of deaths from Scarlet Fever. This could have been the cause of Ms. Chandler’s and her daughter’s deaths.

I believe there is enough evidence to state that Joseph Chandler was the father of Margaret Jane and the spouse of Margaret. Mr. Chandler worked at various laboring jobs while Margaret was employed as a domestic day worker. The couple had a second daughter whose age was only listed as below five years old. There are no other mentions of Chandler family members after the 1847 Census. Mr. Chandler may have moved from Philadelphia.

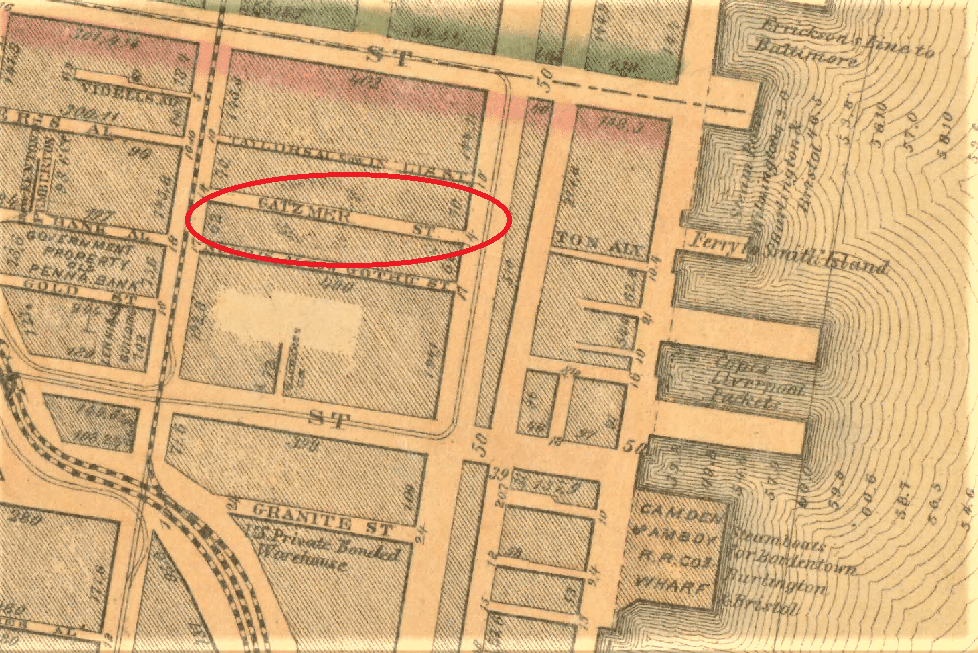

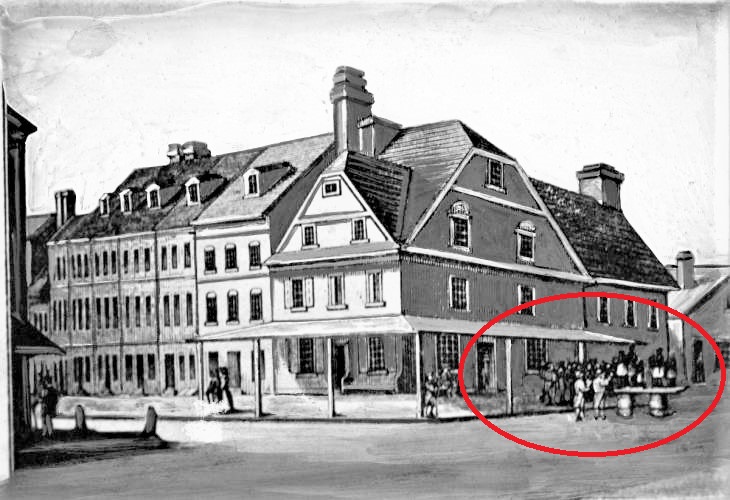

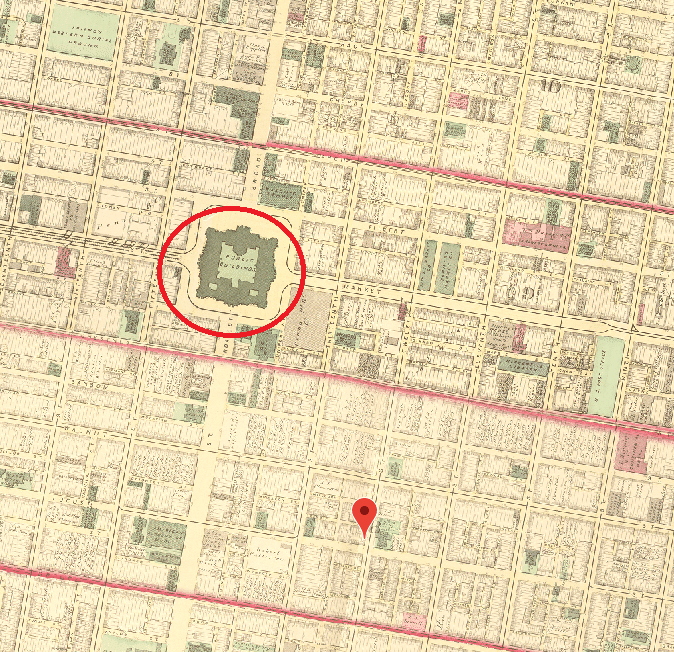

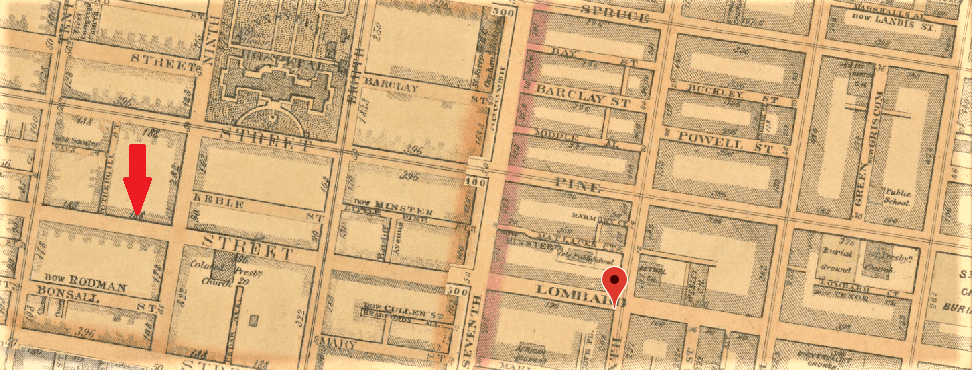

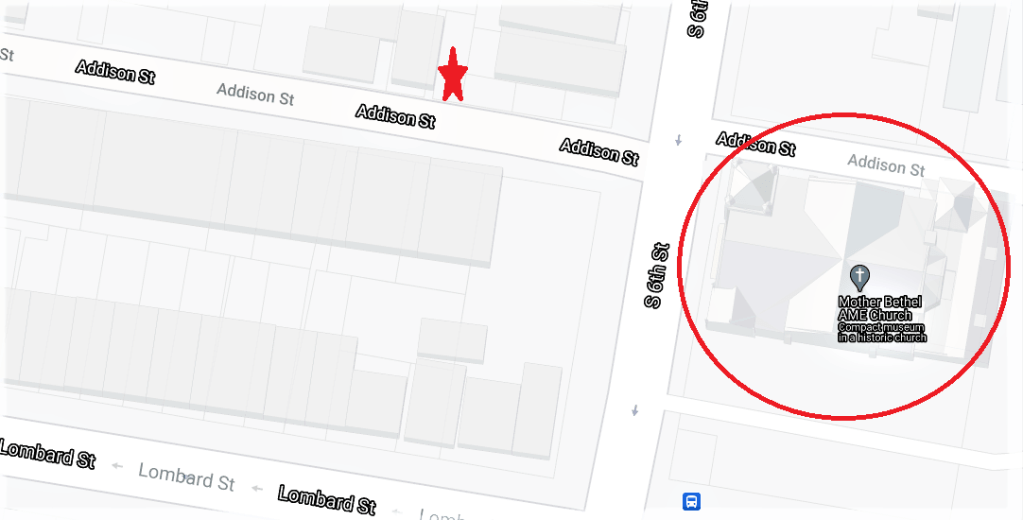

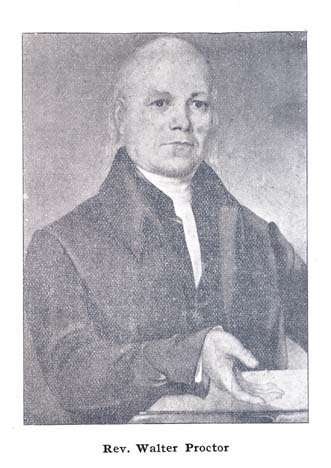

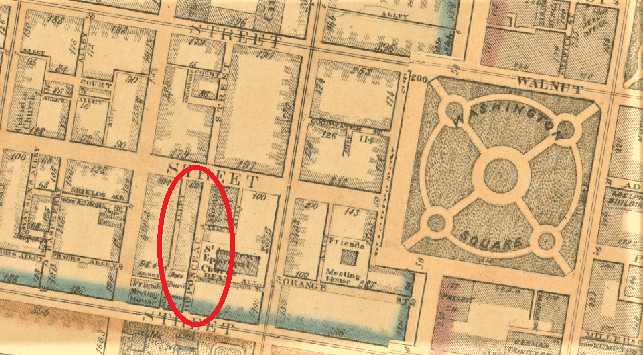

The Chandler family resided at #6 Washington Court. They lived in a 11’x11′ room for which they paid $2.75 a month. Poverty had its grip on the family, given they only had personal property valued at $15, according to the 1847 Philadelphia African American Census. They did belong to a beneficial society at Bethel Church. This was a savings account that could be used to defray burial expenses.

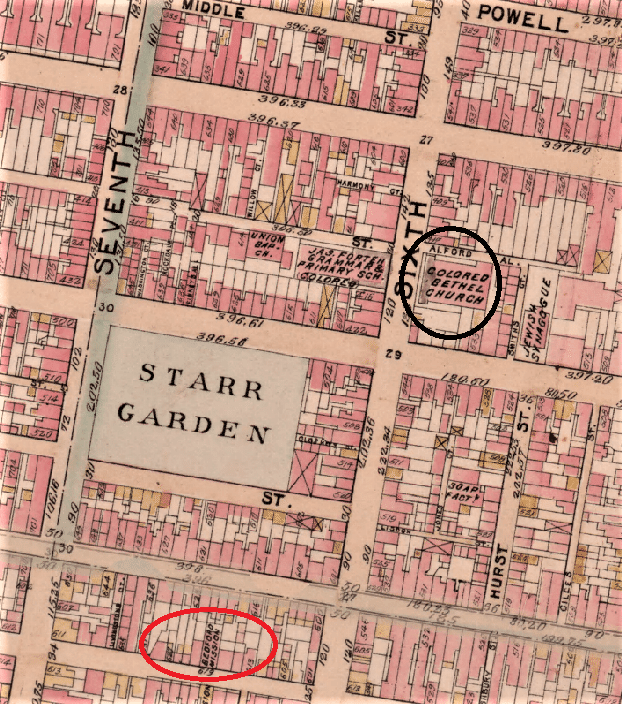

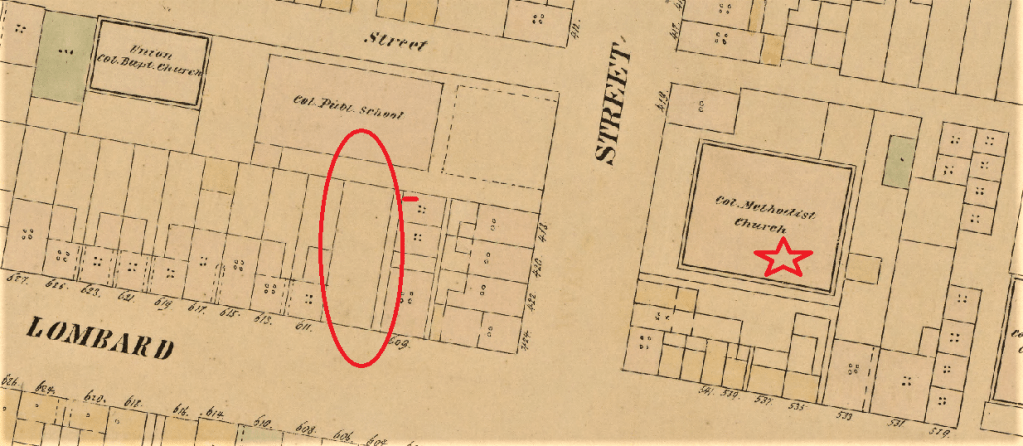

Located close to Bethel A.M.E. Church, Washington Court contained thirty-three Black men, women, and children, according to the 1847 Census. The adults were employed as dressmakers, seamstresses, seamen, hod carriers, and carpenters. They even had their own herb doctor Mr. Randolph Stokes. Their young children attended the 6th and Lombard School.

Upon her daughter’s death, mother and child were buried together at Bethel Bethel Burying Ground. Around eight o’clock in the evening on the day of Ms. Chandler’s death, a “strange cloud formation” appeared in the sky over Philadelphia. According to one newspaper report “This was doubtless a Boreal Aurora in one of its many phases.”(1)

(1) North American, 1 June 1849, p. 1.