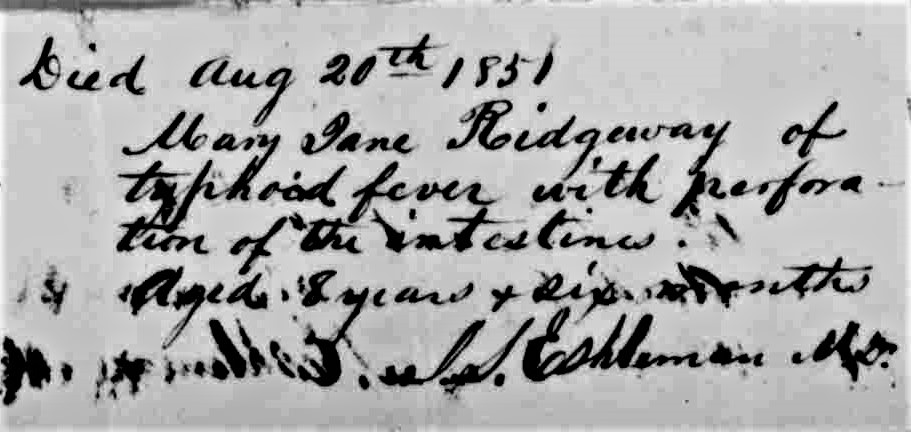

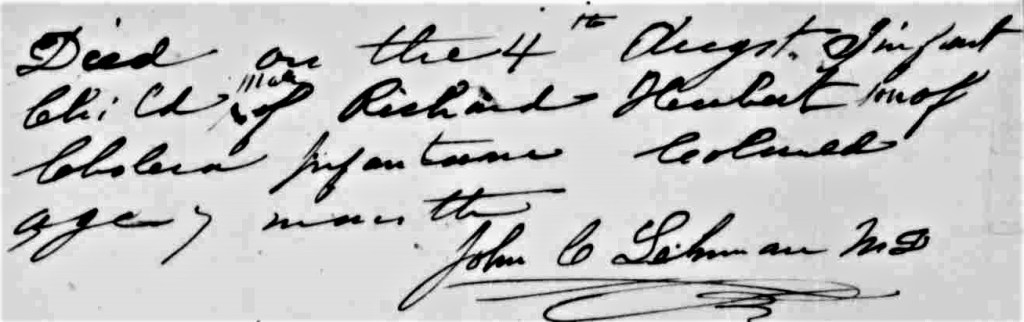

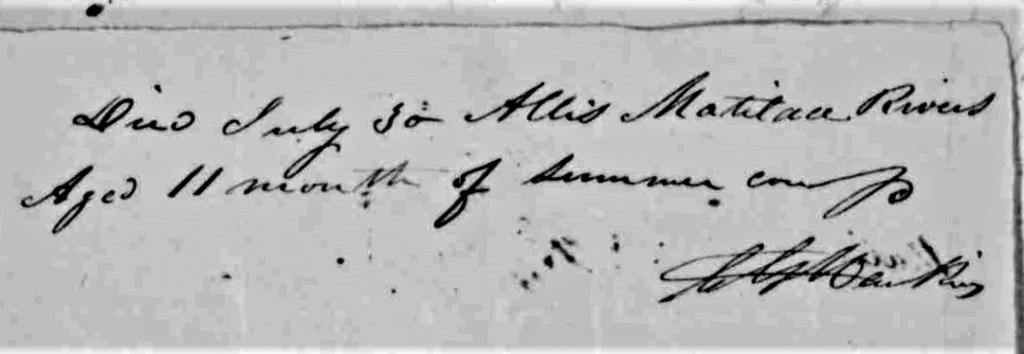

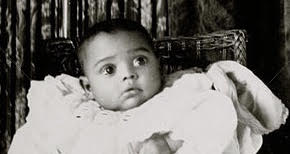

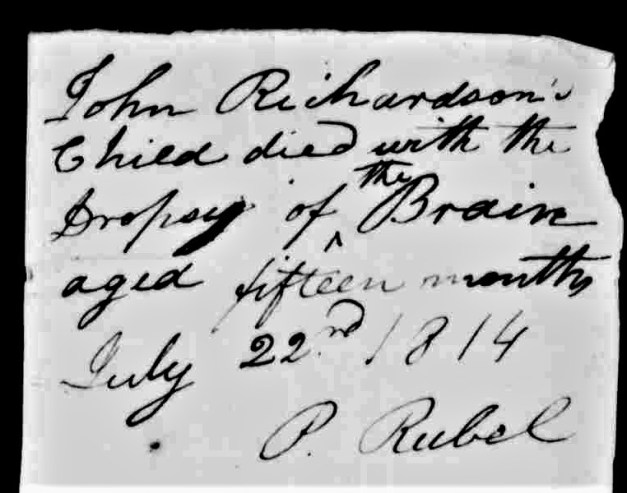

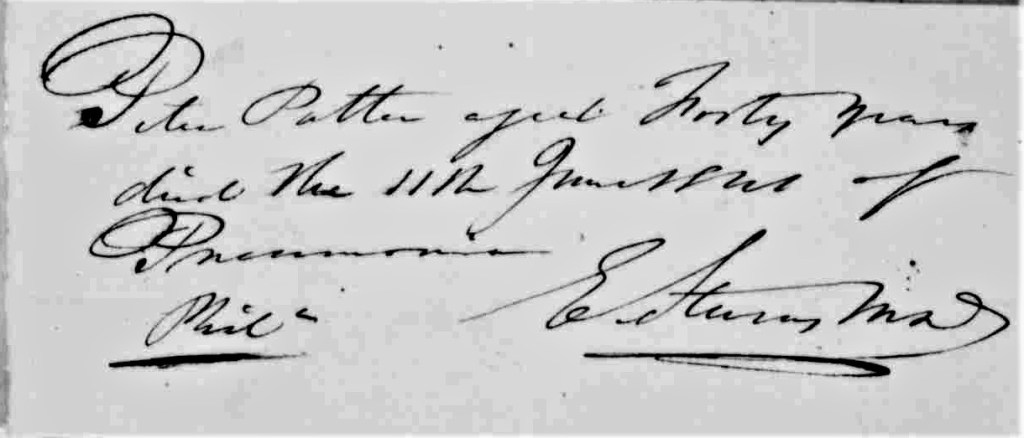

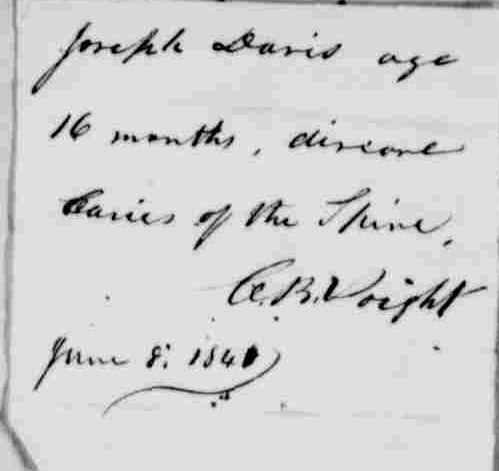

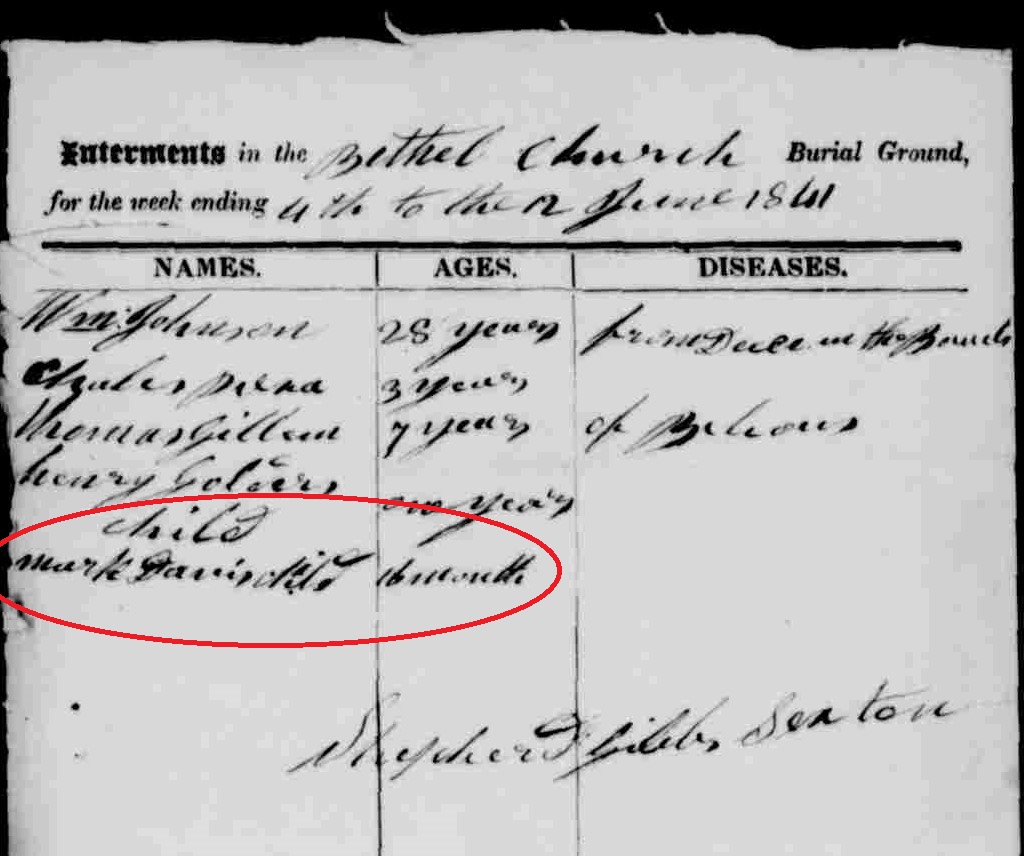

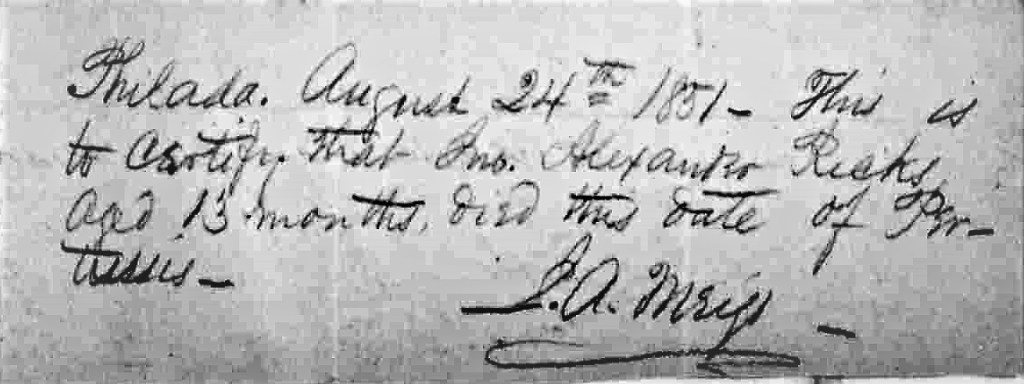

One-year-old John Alexander Ricks died this day, August 24th, in 1851 of Pertussis and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. The disease, which is also called Whooping Cough, is a highly contagious bacterial disease. Children with this disease develop a “100-day cough” that racks their bodies with pain and can lead to broken ribs, pneumonia, seizures, inflammation of the brain, and death. Today, children receive vaccines that successfully prevent the disease.

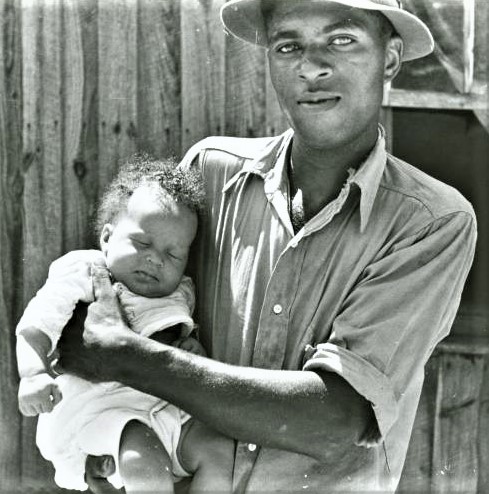

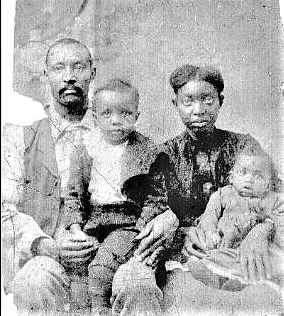

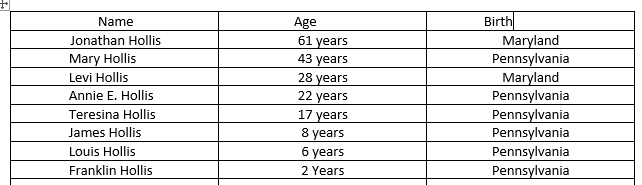

Alexander Ricks’ parents were Sarah and Charles Ricks. Ms. Ricks was twenty-nine-years-old at the time of her son’s death. Mr. Ricks was thirty-five-years-old and he had been born in Maryland. She was born in Delaware, according to the 1850 U.S. Census. They had two other children: William was seven-years-old and Charles was five-years-old. Both were born in Pennsylvania.

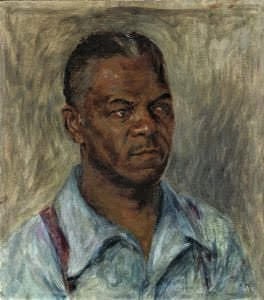

Mr. Ricks was formerly enslaved in Maryland. He reported to the census taker of the 1847 Philadelphia African Census that he was neither manumitted nor had he paid for his freedom. It appears he was a passenger on the Underground Railroad.

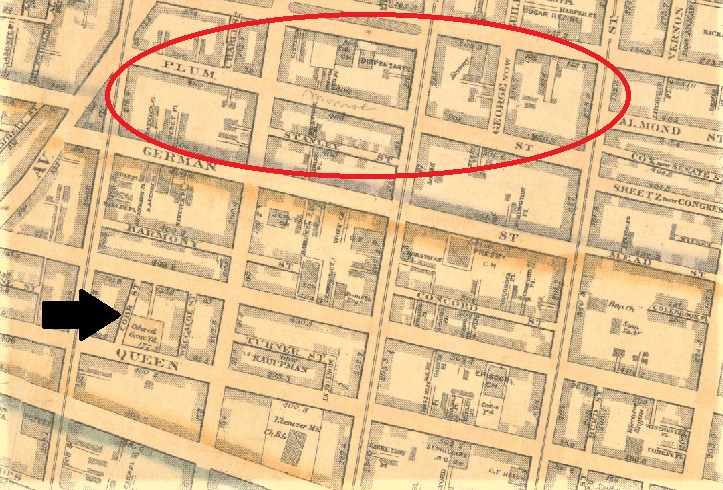

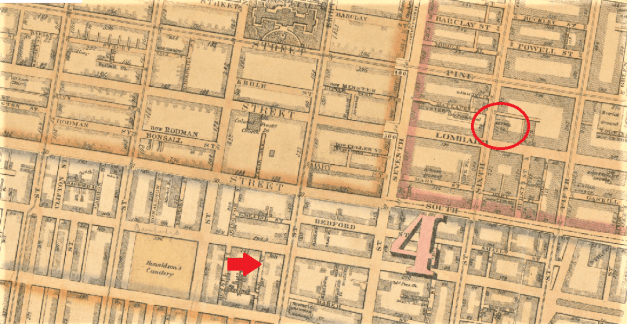

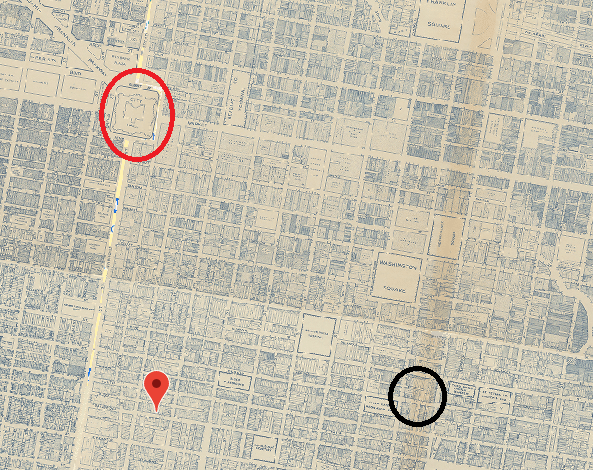

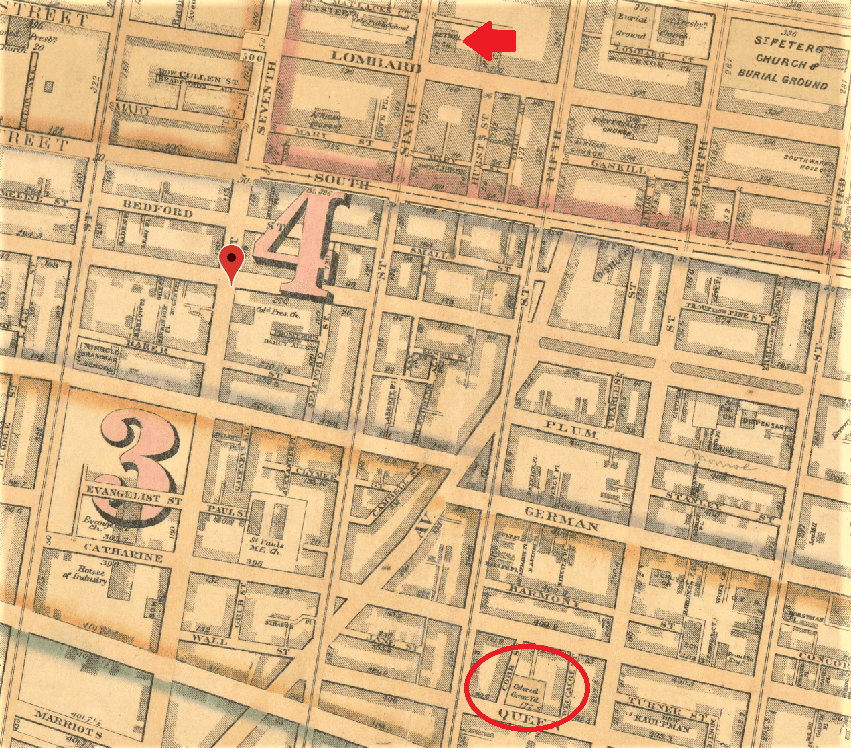

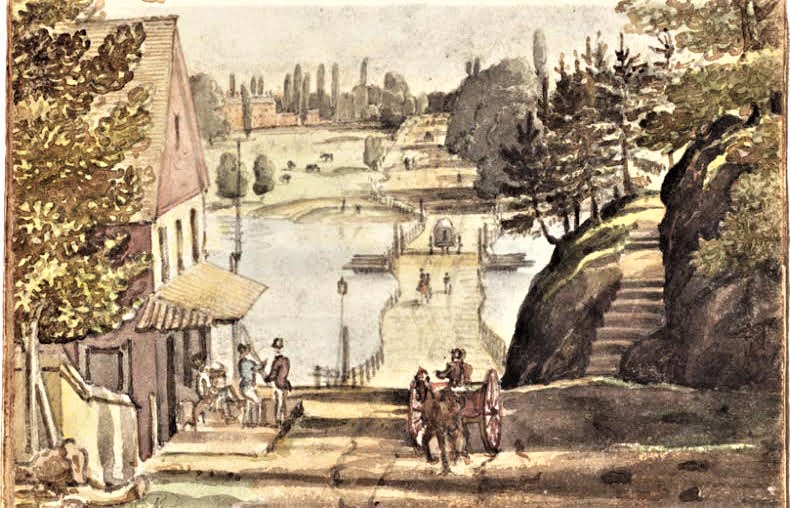

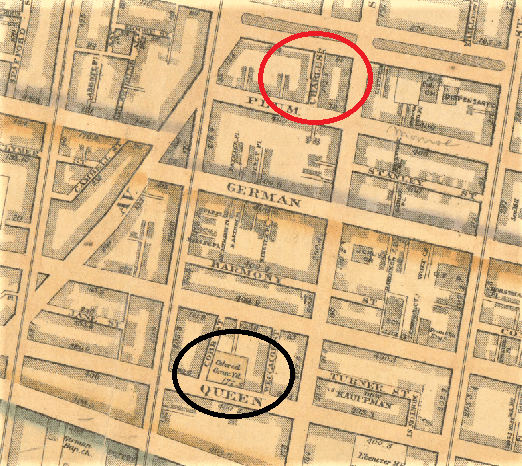

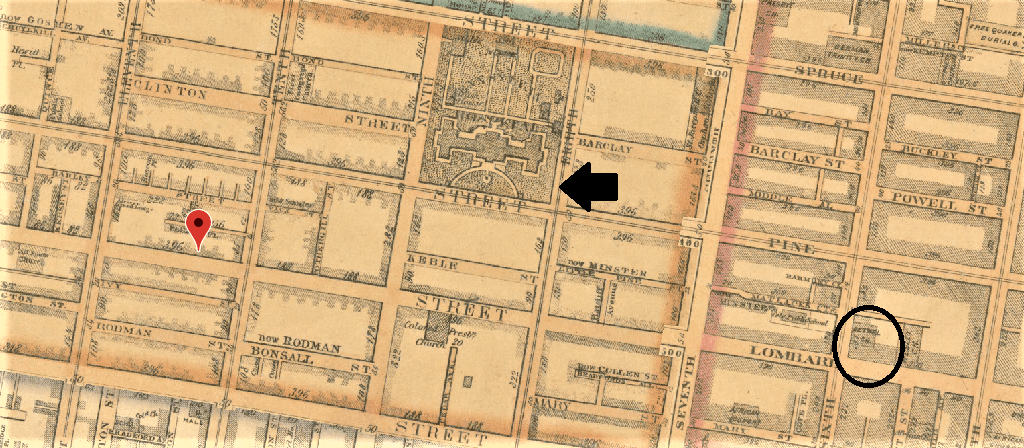

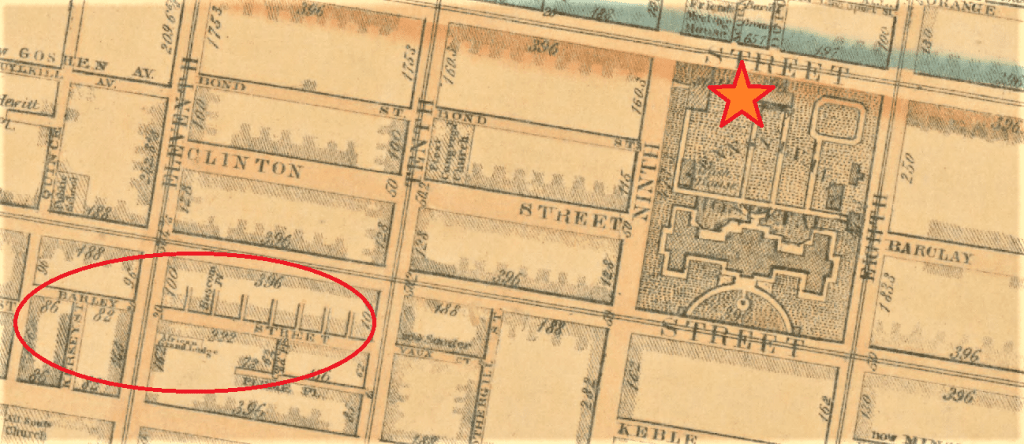

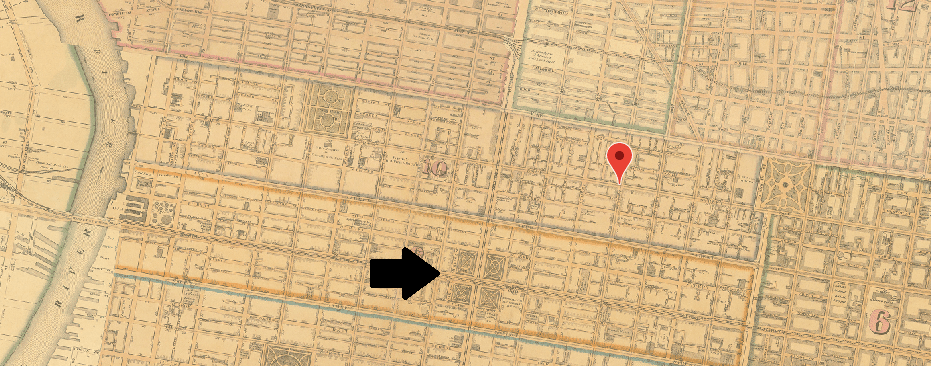

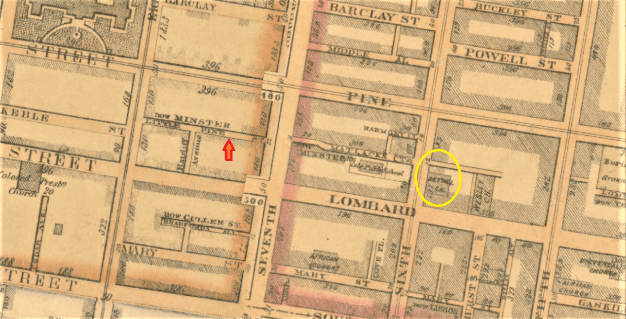

The family lived in one room at #8 Little Pine Street for which they paid $11 a month. That amount is several dollars above average. Mr. Ricks was employed as a coachman and may have owned his own horse and cab. The high rent may have included rent of a stable in the rear of the property. The 1847 Census also reports the family owned $150 in personal property, which may have included the horse and cab. In modern currency that amount equates to approximately $5,000. On a busy week, Mr. Ricks would have earned between $5-$8. Ms. Ricks labored as a laundress and may have earned $1 a week if business was good.

According to the 1847 Census, either Mr. or Ms. Ricks could read and write. But even without that skill, they would have been aware of the most popular book in 1851 Philadelphia. “Negro-Mania” by John Campbell stated that it was God’s will that the Black man was subservient to the white man. The book contained many supporting statements from white businessmen, politicians, jurists, and clergy. They readily led their names to the book’s thesis that the “Colored Race” would never be the “mental, political, or social equal of the white man” And all of the “sickly sentimentalism” and “maudling philosophy” of the abolitionists would not change what God decreed. The African race was created to service the white race.

Frederick Douglass’s comment on race relations in Philadelphia two years before the book was published – “No (Black) man is safe – his life – his property – and all that he holds dear, are in the hands of the mob, which may come upon him at any moment – at midnight or mid-day and deprive him of his all.” (1) These were the streets that the Ricks family had to walk everyday to go to work, market or church.

Between 1850 and 1851, two-hundred thirty-five Philadelphia children died of Whooping Cough. One-year-old John Alexander died on a hot and humid day in late August where the temperature rose to 85 degrees. He was buried, with dignity, by his parents at Bethel Burying Ground.

(1) North Star, 19 October 1849.