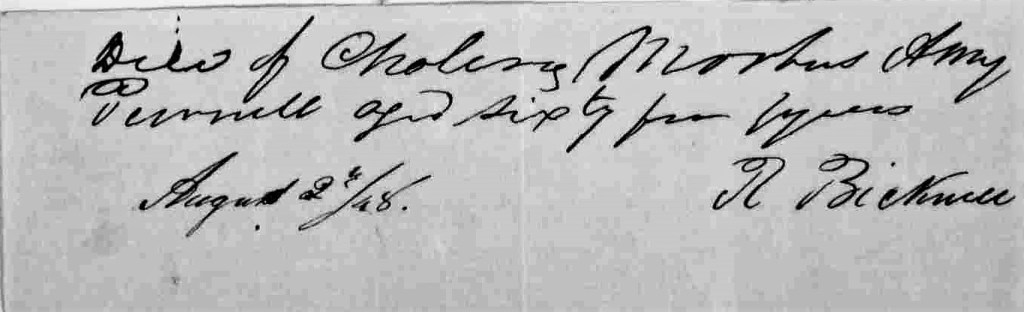

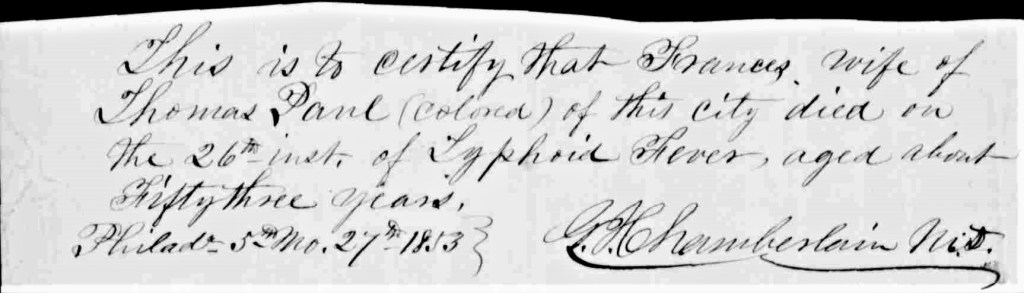

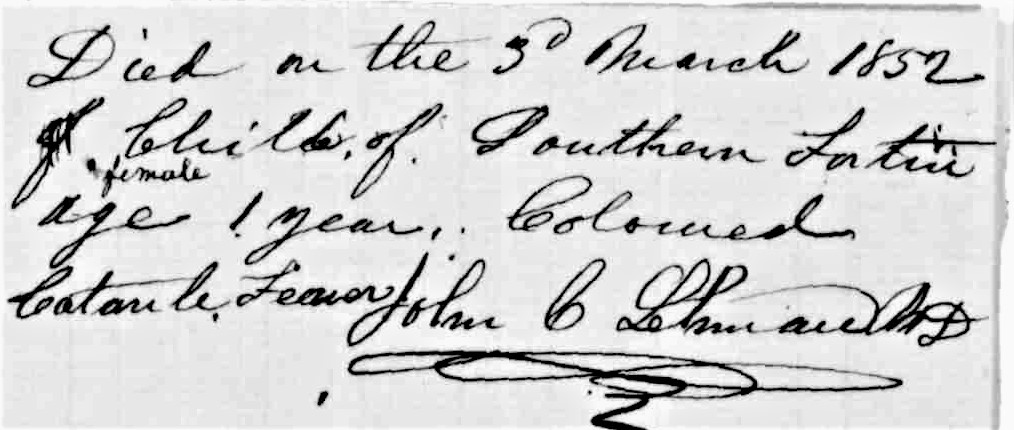

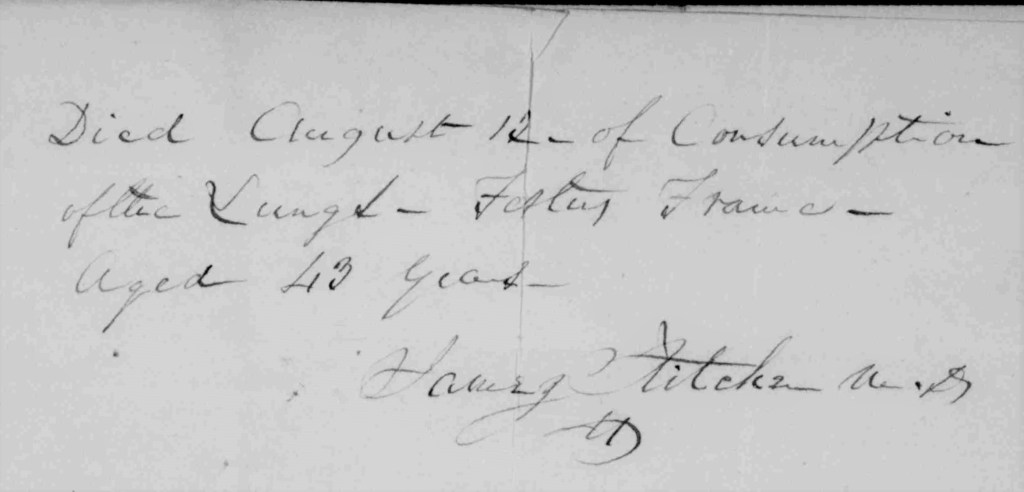

Forty-three-year-old Festus Frame died of Tuberculosis on August 12th, 1847, and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. He is first listed in the 1837 Philadelphia City Directory as ‘Festus France.’ Over the next ten years, he and his family used ‘France’ and ‘Frame’ fairly interchangeably. The problem may have been with the transcribers or that the family was hoping to throw fugitive slave catchers off their trail. According to the 1847 Philadelphia African American Census, where he appears listed as ‘Mr. Frame,’ he and his spouse were previously enslaved. They did not report to the census taker how they were liberated.

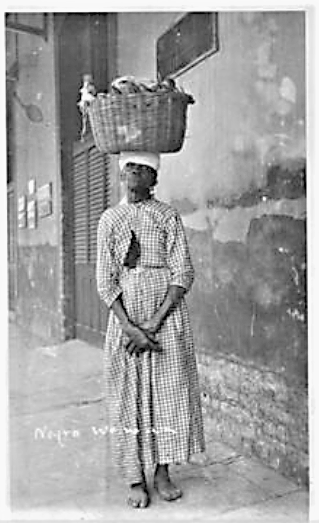

Two mysteries cloud the telling of the family’s story. In the 1838 Philadelphia African American Census, it is reported that Mr. Frame and his spouse owned $700 in personal property or approximately $22,845 in modern currency. They owned their home so that may account for the personal property amount. Mr. Frame worked as a laborer and his spouse was self-employed as a washwoman.

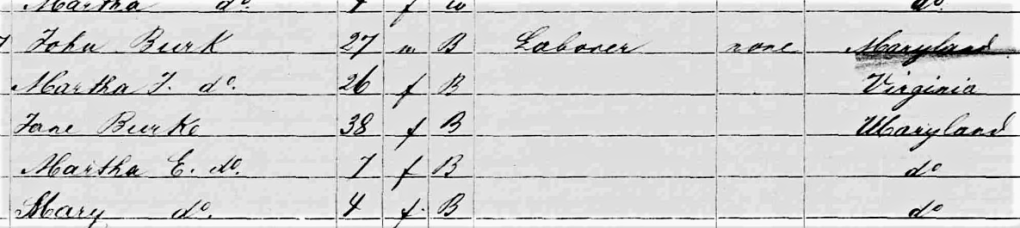

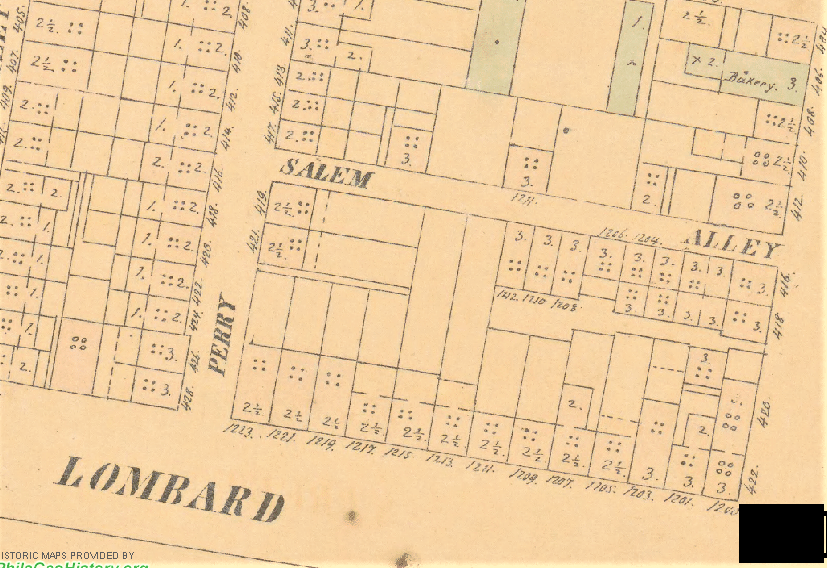

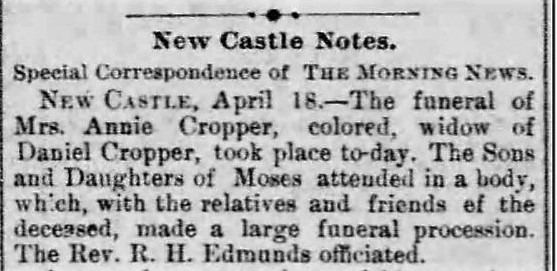

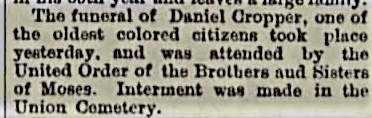

After Mr. Frame’s death, the family address, #10 Acorn Alley, is listed under the name of ‘Sarah Frame’ in the 1850 City Directory. Sarah is listed as the head of the family. Her age is reported to be fifty-five years old and she was born in Delaware, according to the 1850 U.S. Census. This would have been an age difference of eight or nine years between Sarah and Festus.

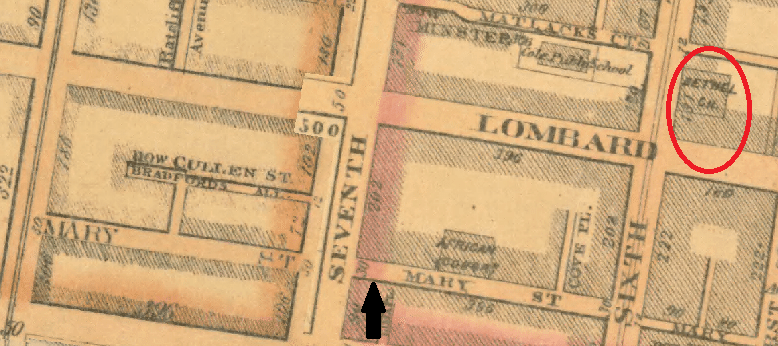

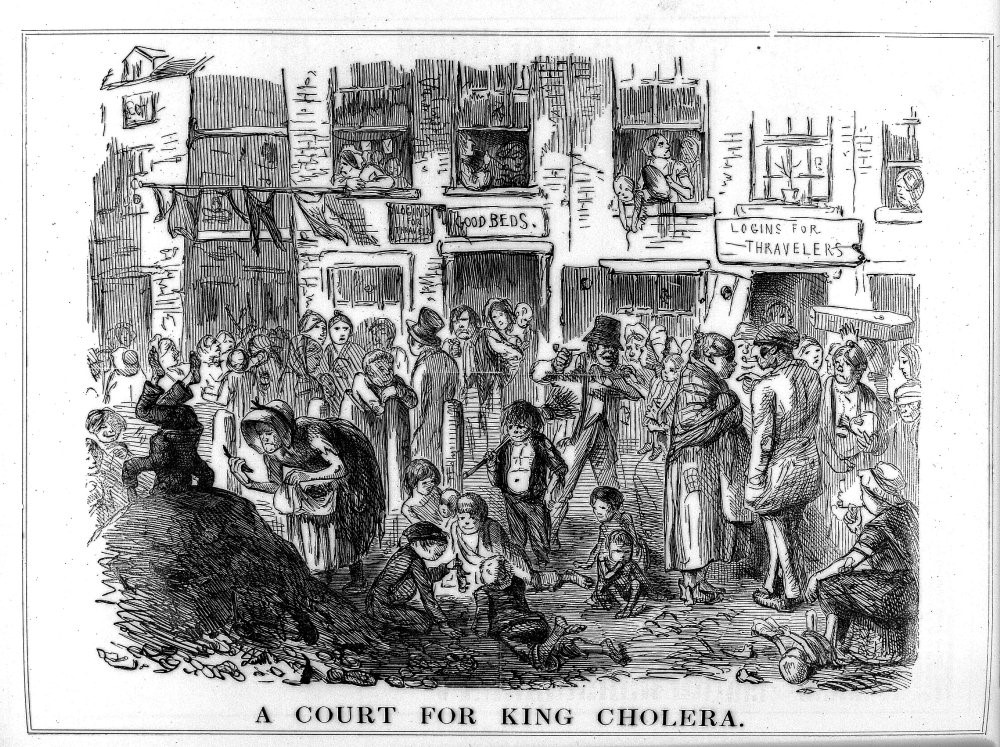

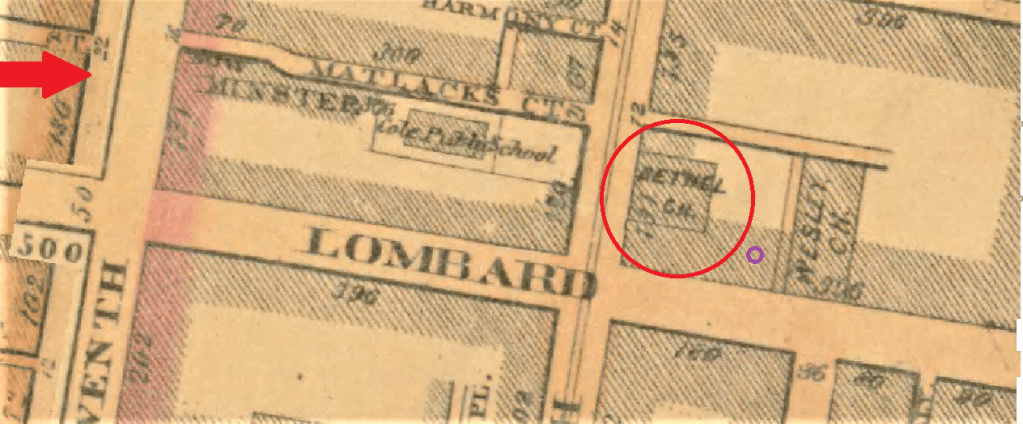

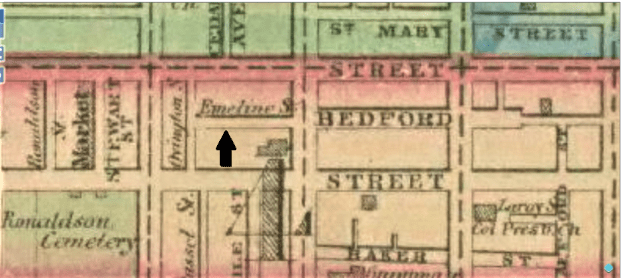

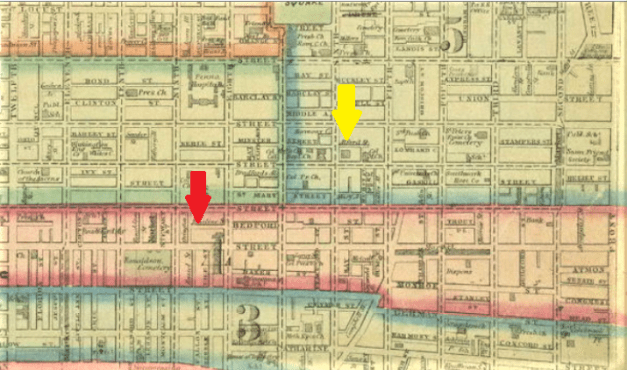

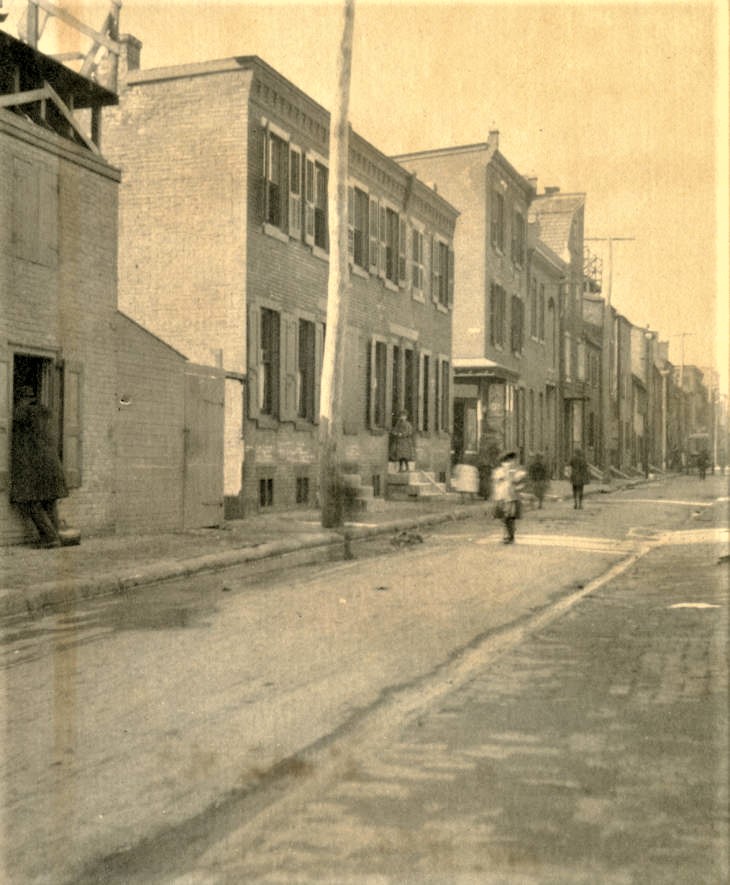

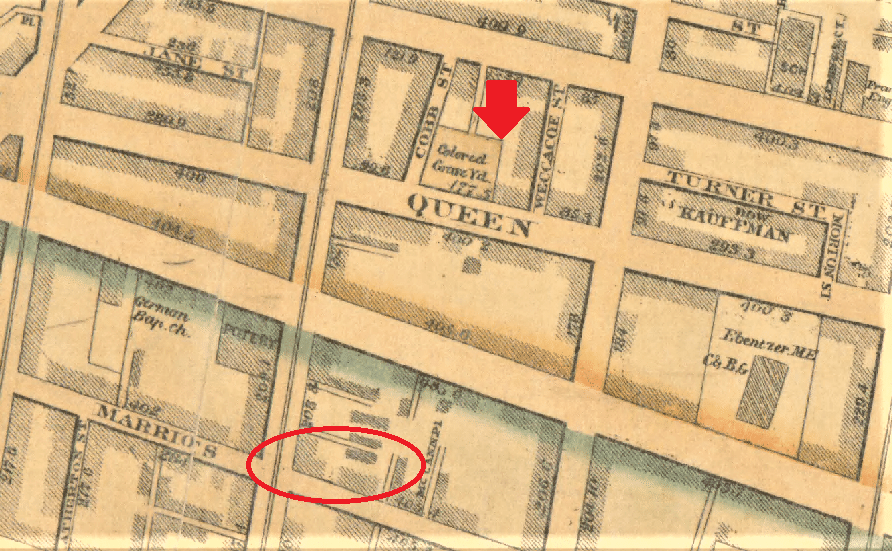

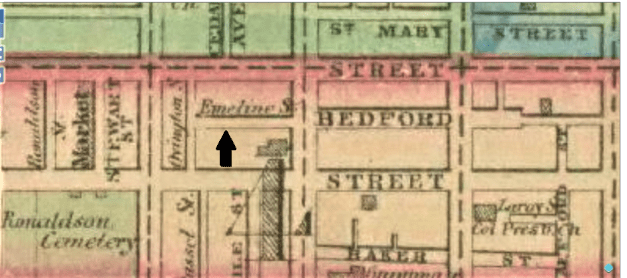

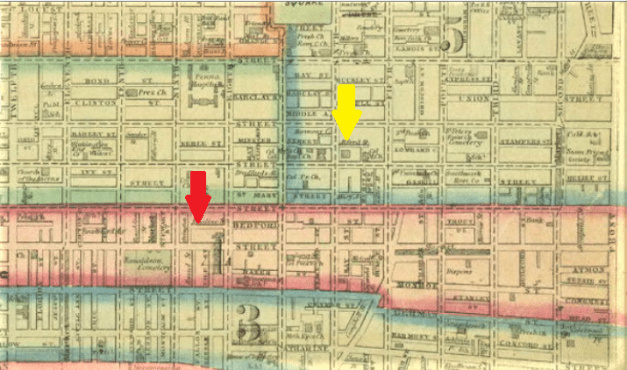

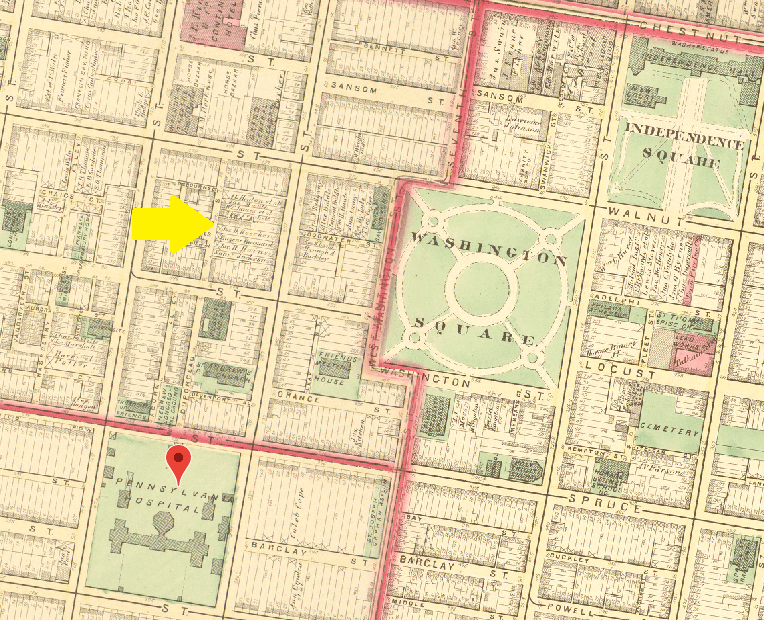

Acorn Alley was a narrow thoroughfare, just west of 8th Street. In 1847 it held at least twenty-one Black families with a total of eighty-seven children, women, and men. The women were employed as laundresses and domestics, while their children attended the 6th and Lombard Infant School or the private schools of Diana Smith or Roger Georges. The men were employed as coachmen, seamen, carpenters, waiters, and oyster house-workers. There was one minister, Rev. John Boggs, who was the Frames’ next-door neighbor at #9 Acorn Alley. (1) He was a key member of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church and an important figure in the Philadelphia African-American community. No doubt he was close to the Frame family as they were Bethel congregants, according to the 1838 Census.

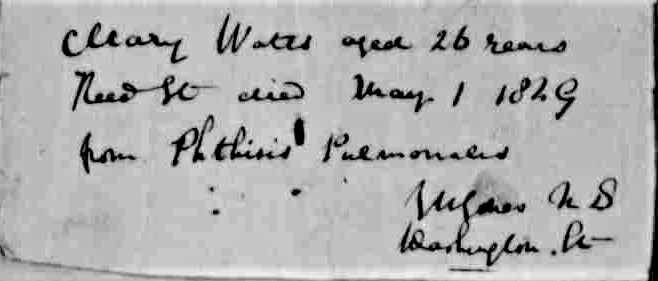

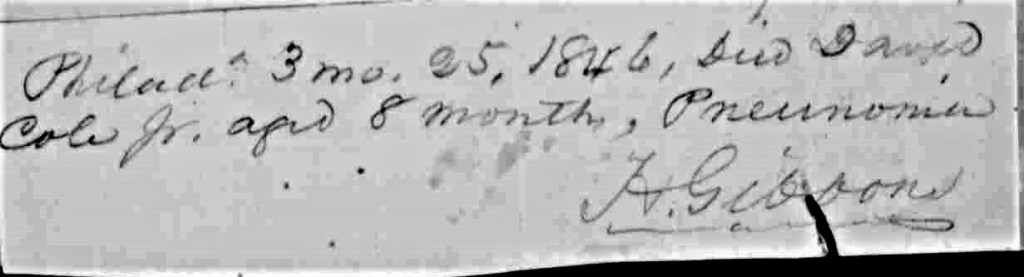

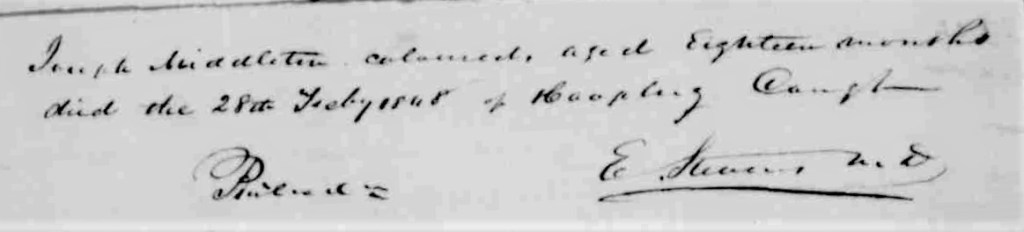

Mr. Frame was one of 1,841 to die of Tuberculosis between 1847 and 1848, according to the Philadelphia Board of Health records. He died on a clear warm day in August that saw the temperature rise to eighty-five degrees by late afternoon. He was buried, with dignity, by his family and friends at Bethel Burying Ground.

(1) Until 1854 the street numbers were consecutive. After 1854 odd number houses were on the north side of the street and even numbered houses were on the south side.