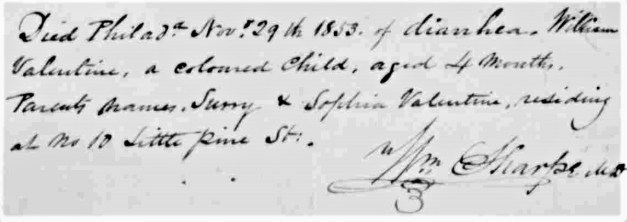

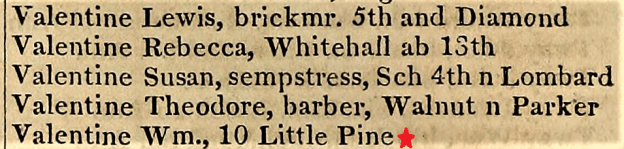

Fifty-year-old Mary George died this date, December 12th in 1847 of Typhus Fever and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. There is not a great deal of specific information on Ms. George. There is a woman by this name whom I presume is this Ms. George in the 1847 Philadelphia African American Census. She was single, poor and cleaned houses for a living.

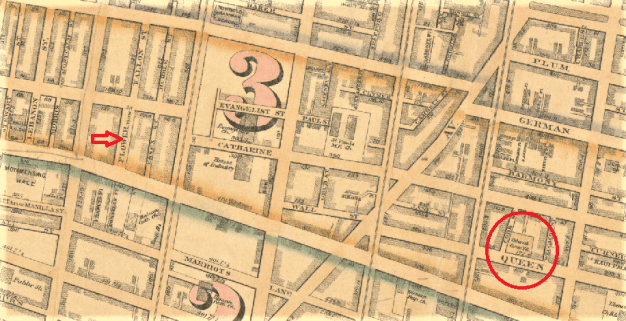

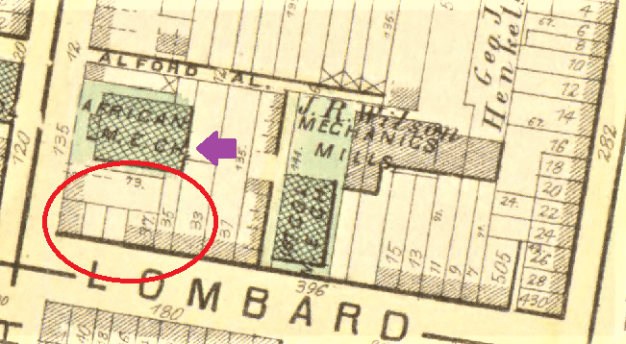

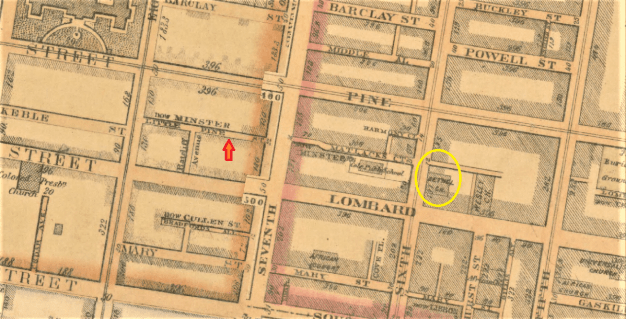

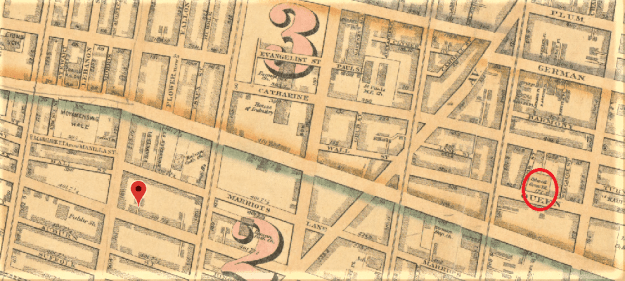

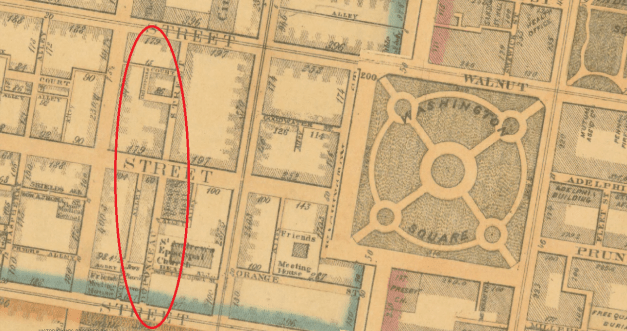

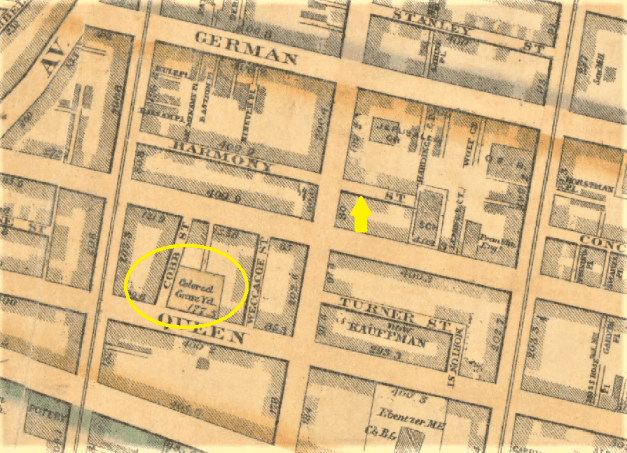

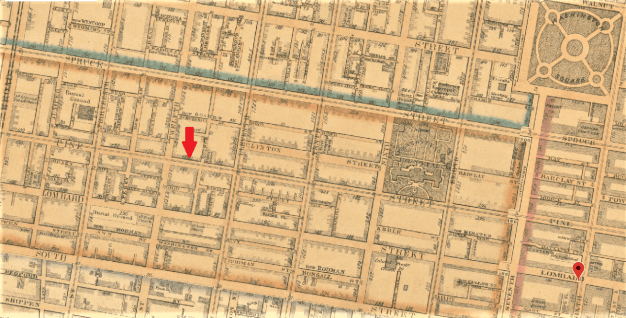

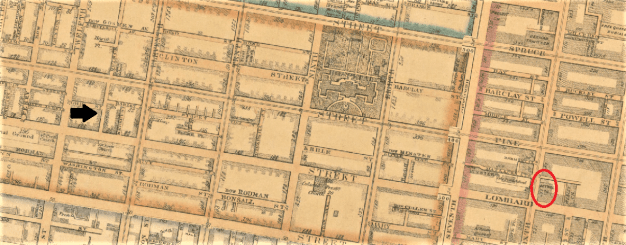

The black arrow illustrates the location of the Quince Street address and the red circle illustrates Bethel A.M.E. Church.

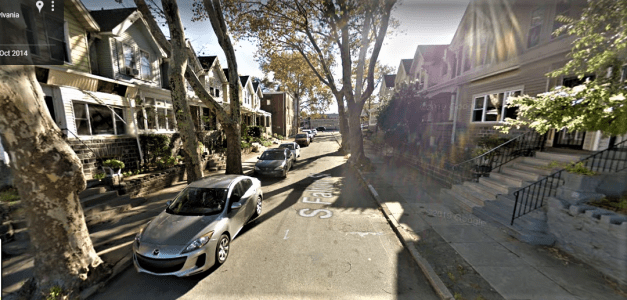

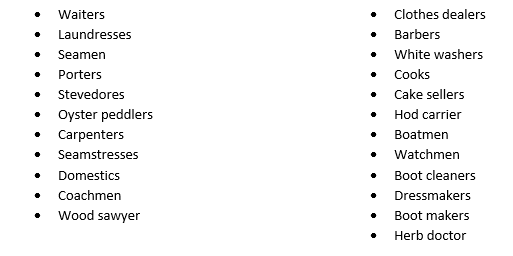

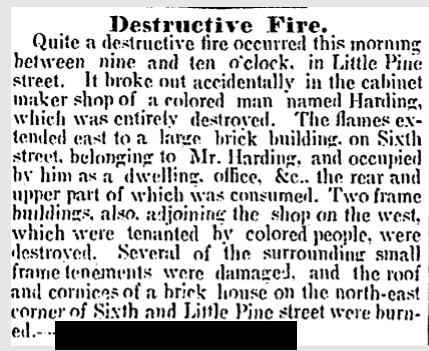

According to her death certificate, Ms. George resided at #32 Quince Street near the intersection of 10th and Lombard Street in center city Philadelphia. According to the 1847 census, that address was also occupied by the Julia Buck family. It appears that Ms. George was either a family member of Ms. Buck or that she just rented space in the one-room home. There were a total of four residents. The women all worked as laundresses and the only male was employed as a hod (brick) carrier.

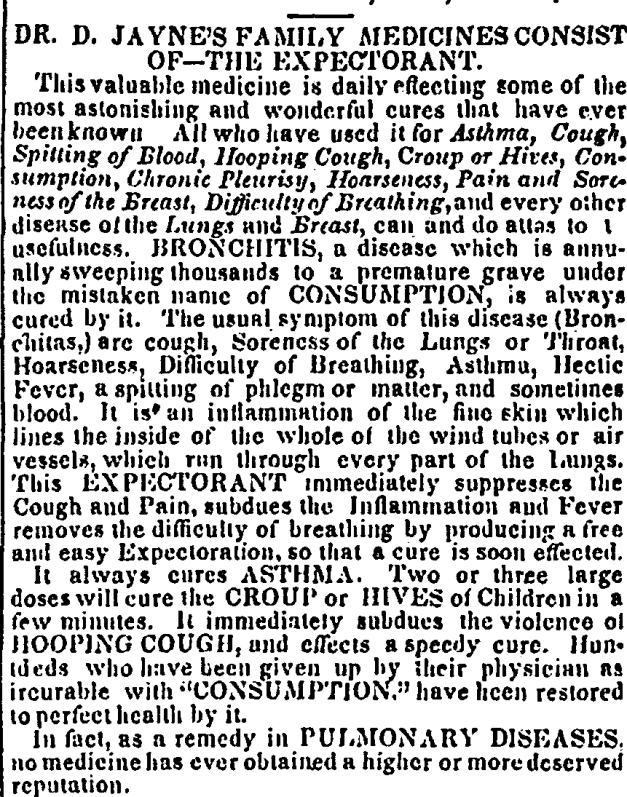

Approximately three weeks before Ms. George died, she was bitten by a flea that likely came from a rat. The bite transmitted a bacteria into Ms. George’s bloodstream. During the next 2-3 weeks, she experienced excruciating pain and a series of ever-increasing symptoms. These included high fever, vertigo, headaches, fatigue, blindness, loss of hearing, hallucinations, episodes of cold chills and hot flashes. As the end of her life neared, Ms. George would have been racked by vomiting, throat and lungs inflammation and unremitting pain in her legs, back, and groin. Finally, the bacteria would enter her central nervous system causing an even higher fever and deadly convulsions.

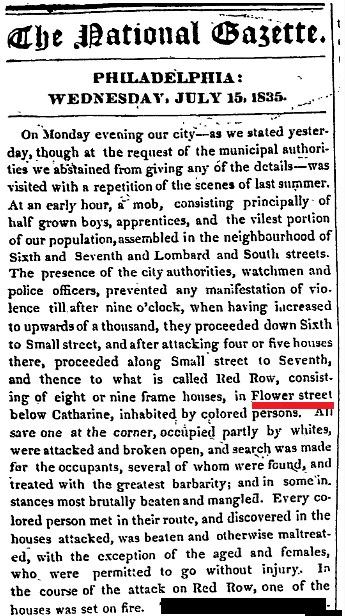

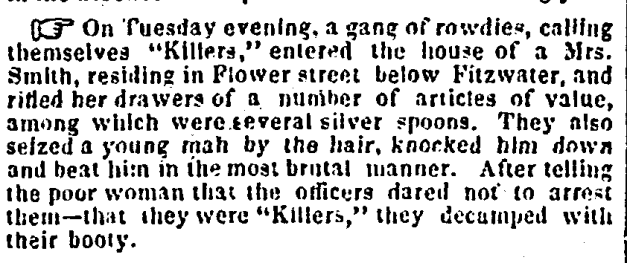

Ms. George was one of the 254 Philadelphians to die of Typhus in 1847. The vast majority were destitute and lived in awful conditions. Many of the sick died alone and uncared for in desolate rooms, boarded shanties, and damp pitch-black cellars. The last epidemic of Typhus in Philadelphia occurred during the winter of 1835-36 among a large group of recent Irish immigrants. At that time, the Board of Health recorded 241 deaths. In 1847, the year that Ms. George died, a total of 254 Philadelphians succumbed to Typhus. Although the number who died from Typhus that year was very high, it was not declared an epidemic by the government.

Ms. George died during a week that saw a startling rise in temperatures that resembled more like “the first of April than December.” Daytime temperatures rose to the high 60s and low 70s. The city streets turned to mud and made walking and transportation difficult.