BBG TIMELINE (click on)

BBG TIMELINE (click on)

Forty-five-year-old Mary Polk died this date, May 25th, in 1850 of a “congestive brain” and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. The term “congestive brain” can mean several things, but is most commonly a catch-all phrase for a stroke. According to 1850 Federal Census and the 1847 African American Census, Ms. Polk was married and mother of a daughter Caroline (18) and two sons Richard (13) and William (16) who was appreciating as a barber. She lived with her family in a shanty/shack in the backyard of 11 Prune Street which would currently equate to 411 Locust Street just east of Washington Square. Her residence is marked with a red X on the 1840 map below.

Mary Polk worked as a washwoman earning approximately $1.40 a week while her husband earned $1.50 a week as a laborer, according to the 1847 African American Census. This family was living on approximately 35% of what the average Black working poor were earning. They were paying $3.00 a month for what W.E.B. DuBois termed a “backyard tenement.” A dilapidated one-room shed/shack without heat, sewer or water. For more on this type of housing and environment see DuBois’ “The Philadelphia Negro,” especially pages 307-09 and 293-95.

The Polks belonged to a beneficial society where they saved money probably toward burial expenses. The family worshiped at Bethel Church (now Mother Bethel AME).

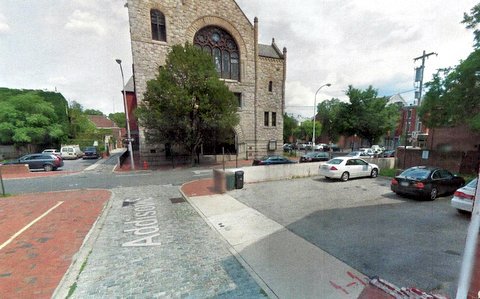

Twenty-four-year-old Mary Jane Laws died this date, May 21st, in 1848 of an intestinal disorder (Gastritis) and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Ms. Laws lived across the street from Mother Bethel Church on the corner of Little Pine St. (now Addison) and 6th Street.

The Laws’ residence would have been situated where the white car is pictured. Ms. Laws is one of a dozen of the Laws family (that we know of) that are buried at the Bethel Burying Ground. Stephen Laws was an original trustee of Mother Bethel who died in 1814 and was also buried at the Bethel Burying Ground.

Four-year-old William Ayres died this date, April 28th, in 1850 after being crushed to death by a horse-drawn trolley and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. I was unable to positively identify the child’s parents. There are some clues, but nothing definitive.

Ironically, there was an eight-year-old child killed in the same manner 11 days before the death of little William. The Public Ledger reporting the death stated that there were a high number of children being killed in the city by hanging onto the back of these vehicles, falling and subsequently being run over by other vehicles. The newspaper wondered, even with he high number of deaths, why there weren’t more accidents given the danger. (4/17/1850 p. 1)

The vehicle that crushed the child was the Omnibus No. 12 owned by John Levering. It would have looked similar to the one in this photo.

These “horse buses” were the later cousin of the old stagecoach and could carry many more passengers. The service was established throughout the city of Philadelphia in 1831. These were the predecessors of today’s trolleys and buses.

Fifty-four-year-old George Miller died this date, April 11th, in 1842 of Tuberculosis and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. I have not been able to locate him in census records or city directories. This is not at all uncommon. Those that had escaped their enslavers and found their way north to Philadelphia would not welcome their presence published if they could avoid it. Mr. Miller was employed as a woodsawyer according to his Death Certificate. He lived in one of the worst neighborhoods in the 7th Ward. St. Mary’s Street was the epicenter of Black vice that included prostitution, gambling, and illegal speakeasies. It is where the poorest of the poor lived in conditions that are hard to imagine. Mr. Miller lived only about a block and a half from Bethel Church (now Mother Bethel).

Twenty-four-year-old Elizabeth Melony died this date, April 4th, in 1823 of “nervous irritation” and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. She lived on Lombard Street near 7th Street only a block away from Bethel Church.

The term “nervous irritation” can mean many things. After reviewing a fair amount of material it commonly meant, during this time period, a disease of the brain. It also referred to “hysteria” in women. A phenomenon that was due to ignorance and a misogynistic culture. For further reading, I found “Sex, Sickness and Slavery: Illness in the Antebellum South” by Marli F. Weiner to be helpful in understanding the disease as it related to 18th and 19th-century African American women; see pages 139-142, Some parts of this book are available online at GoogleBooks.

Three-year-old Isaac Lee died this date, March 8th, in 1849 of Catarrhal Fever and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Researching census data it is likely that Isaac was the son of Mary Isaac. His father’s name is not recorded and it is reported that he was physically unable to work. Mary’s occupation was as a “day worker.” They paid $5 a month for their room. They had no other children.

Mary or her spouse were reported to have been previously enslaved and gained their manumission by paying $100. It is possible that Mr. Lee’s disabilities occurred while he was enslaved and that is why the manumission price was so low.

Catarrhal Fever is similar to Influenza – inflammation of mucous membranes, especially of the nose and throat.

The house that the Lees lived in was soon torn down after Issac death and the grand Continental Hotel was build at 9th and Chestnut. It is now known as the Ben Franklin.

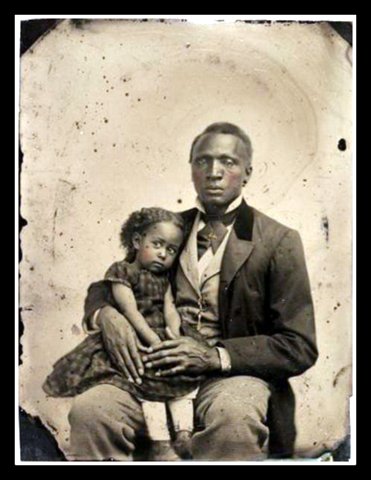

The three-year-old daughter of Spencer Logan died this date of Scrofula (Tuberculosis) and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. According to the 1847 African American Census, Mr. Logan was employed as a porter and his spouse ( name unknown at this time) was employed as a laundress. They lived in a small room at 4 Bonsall Street for which they paid $2.50 a month for rent. Bonsall is now Rodman Street and the building would have been in the 900 block of Rodman. Several prominent Black families lived on this block including the LeCounts (#6) and the Bolivar family (#8). Both Mr. and Ms. Spencer were born enslaved and gained their legal liberation through manumission. It appears that both were born in Virginia.

Unidentified father with his baby girl

Laundress

Thirty-two-year-old Henry Matthew died this date, February 3rd, in 1853 of Tuberculosis and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. He was a native Philadelphian who employed as a boat builder. He was probably a sailmaker as his previous profession was cordwainer or someone who make boots and shoes from new leather; as opposed to a “cobbler” who repaired worn shoes.

A Black man who was employed as a sailmaker in all likelihood worked for James Forten (September 2, 1766 – March 4, 1842) “an African-American abolitionist and wealthy businessman in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Born free in the city, he became a sailmaker after the American Revolutionary War. After an apprenticeship, he became the foreman and bought the sail loft when his boss retired. Based on the equipment he developed, he built a highly profitable business. It was located on the busy waterfront of the Delaware River, in the area now called Penn’s Landing.” See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Forten

Mr. Matthew was married and lived at 56 Currant Alley (now S. Warnock St.) a small narrow alley that ran from Walnut St. to Spruce St. between south 10th and 11th streets. In the 1847 African American Census at least 85 Black families lived on this small narrow alley. The Matthew family is not listed in the 1850 Federal Census for the City of Philadelphia. His death certificate was signed by J.J. Gould Bias, M.D., an African-American gentleman, a friend of Rev. Richard Allen and a valued member of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Currant Alley (now S. Warnock St.) as it looks today.

Stephan Salisbury, CULTURE WRITER, Philadelphia Inquirer

POSTED: Monday, February 1, 2016, 1:07 AM

The lost 19th-century graveyard established by Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and utilized heavily by the city’s black community until shortly after the Civil War, has been named a National Historic Site by the federal government.

The existence of the graveyard had been forgotten until rediscovered by a historian a few years ago and designated a city landmark in 2013.

Bethel Burying Ground now joins a handful of city graveyards – Christ Church Burial Ground, Old Swedes’ Church Cemetery, Mikveh Israel Cemetery, the Woodlands – on the national register.

Most important, the designation earlier this month puts the graveyard in the national spotlight at a time when the Queen Village site, beneath Weccacoe Playground, remains contested ground, caught between conflicting interests of neighbors, historians, the black community, church officials, and an up-to-now uncommunicative and lethargic city bureaucracy.

Even as national importance has been certified, some community leaders and preservationists are alarmed by reports that the city is about to begin construction on the playground, possibly imperiling the historical integrity of the burial ground.

The graveyard, beneath about a third of the three-quarters-of-an-acre playground in the 400 block of Queen Street, is owned by the city. More than 5,000 18th- and 19th-century African Americans are buried there, members of the city’s and nation’s “founding generation,” in the words of Richard S. Newman, director of the Library Company of Philadelphia and author of Freedom’s Prophet, a highly regarded biography of Richard Allen.

The city had agreed to renovate Weccacoe before the burial ground was rediscovered through the research of independent historian Terry Buckalew.

Officials of the Queen Village Neighbors Association and Councilman Mark Squilla said that they have been recently notified by the city that work on the playground is about to commence.

No renovations have begun, however, and no construction plans have been filed with the Philadelphia Historical Commission.

Seeking to allay concerns, city Managing Director Michael DiBerardinis said Thursday that construction is not imminent.

“Mayor Kenney and I are currently in discussions with various stakeholders regarding the planned renovations at Weccacoe Playground and the development of a memorial at the burial site,” DiBerardinis said in an email. “A construction date has not yet been set for the playground renovations. We look forward to providing more information regarding this important project as those conversations progress.”

Even if construction did begin, officials contended, it would not directly affect the Bethel ground.

Planned work includes “new play equipment, a spray park, new seating and trash receptacles, repairs to the perimeter fence, renovations to the portion of the tennis court not located over the burial ground, and a garden to manage storm water,” according to a December email from Everett Gillison, then-Mayor Nutter’s chief of staff.

A substantial portion of the graveyard lies beneath a Weccacoe tennis court; some graves are little more than a foot from the surface.

Former city Managing Director Joe Certaine, a leader of an ad hoc group, Friends of Bethel Burying Ground, is scheduled along with several others to meet with Mayor Kenney and DiBerardinis on Monday.

Certaine, not happy with the process so far, argues that the city, owner of the site for more than a century, has ceded decision-making to local neighbors and officials at Mother Bethel AME Church, Richard Allen’s home base at Sixth and Lombard Streets. The cemetery “needs to be treated as a taxpayer-owned historic site” belonging to the whole city, he said.

The city has failed to consider the broad historical relevance of Bethel, Certain said.

“Until the public understands the historic value that this site represents to the African American community, nothing positive will be done to protect and preserve it,” he said.

What particularly rankles Certaine and many others is the presence at Weccacoe of a large community building, constructed in the 1920s and expanded in the 1970s. It sits on a concrete pad directly over the heart of the burial ground and is now used as office space by the neighbors association.

Certaine and many others consider the building and its toilets an unseemly desecration of sacred ground.

Michael Coard, attorney and leader of the Avenging the Ancestors Coalition, says, “You move the playground. You move the bathroom. You treat it as hallowed ground. That’s just respect. The city is allowing the ancestors to be desecrated.”

But the Rev. Mark Tyler, Mother Bethel pastor, believes that the community center potentially could be part of an interpretive plan informing visitors – and children using the playground – of the significance of the cemetery.

And he points out that demolition of the building poses its own threats to the historic area.

Councilman Squilla and leaders of the neighbors association agree with Tyler, arguing that both playground and burial ground can coexist in close proximity.

“There are plans for the playground, keeping in mind the sanctity of the burial ground,” Squilla said. “There will be meetings determining the next step.”

In the meantime, Buckalew, the historian whose work rediscovered the burial ground and who has now identified about 2,400 people buried there, is concerned with the structural integrity of the community building.

He said that, in the last 18 months, a crack has appeared, running from roofline to the ground and extending out onto the asphalt west of the building. A new roof-to-ground crack was noted last week on the building’s south side.

Buckalew, a retired facilities manager at the University of Pennsylvania, believes that the cracks are the result of “settling.” In other words, the graves below are collapsing and the ground is sinking. (Archaeological studies have noted other sinking areas above the cemetery.)

“I’m very concerned about water seeping through the cracks and down into the graves,” said Buckalew.

“We need an engineering study of the whole site.”

Such a study has been requested for nearly three years, but has not been done so far.

“You need an engineering study to proceed safely,” Buckalew said.

(To read stories of those buried at Bethel Burying Ground, many of them children and infants, visit Buckalew’s website devoted to the research: bethelburyinggroundproject.com)

215-854-5594