Twenty-three-year-old Josiah Durham drowned in the Delaware River on this date, August 12th, in 1841 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. While working on the steamboat “Ohio” Mr. Durham fell overboard in the dead of night and drown. The steamboat was an excursion vessel that was “one of the most beautiful boats on the river.” (Philadelphia Inquirer, May 3, 1833.) Mr. Durham lived in Prosperous Alley which ran south from Locust Street, above 11th Street.

On This date

James F.T. Rodney, 3 years old, died this date, August 5th, in 1849 of Hydrocephalus* and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. The child was the son of Ann Elizabeth Rodney, a single mother who had four other children in her care. The Rodney family lived in extreme poverty in a room in Madison’s Court which was in the rear of 7th and St. Mary’s Streets for which Ms. Rodney paid $2.50 a month. The neighborhood was one of the worst in the city but was affordable for a woman who took in washing for a living while raising 5 children. All the children attended school. It appears that James, before his death was enrolled in the Lombard Infant School. Their home was only two blocks from Bethel Church at 6th and Lombard where the family attended services. (1847 African American Census)

*Hydrocephalus is an abnormal increase in the amount of cerebrospinal fluid that circulates in the brain. this puts increased pressure on the brain that produces an enlarged head and may lead to brain damage. The condition is associated with spina bifida, viruses, bacteria and funguses. (A Biohistory of 19th-Century Afro-Americans, Lesley M. Rankin-Hill)

Charles Jones, 30, died this date, July 30th, in 1813 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. He died after being crushed under the wheels of a cart. The City Coroner ruled the death an accident. Mr. Jones was occupied as a woodsawyer and lived at 328 S. 6th Street only two blocks from Bethel Church.

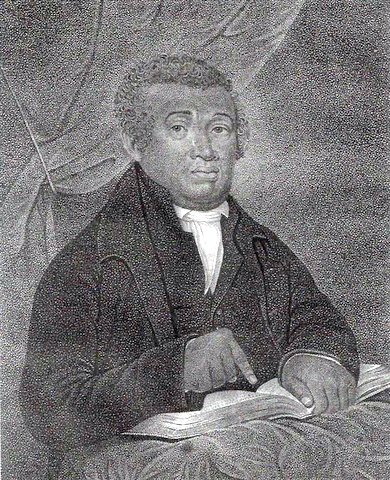

A portrait of Rev. Richard Allen painted in 1813 the year of Mr. Jones’ death.

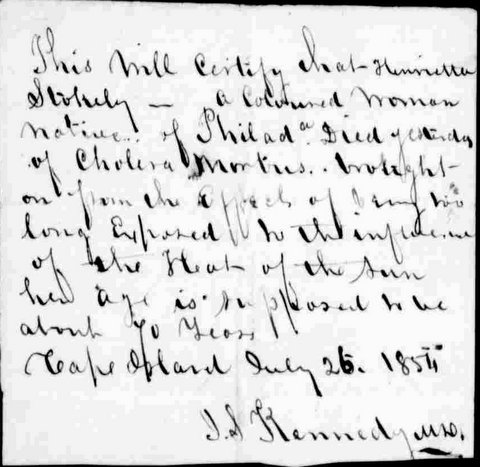

Seventy-year-old Henrietta Stokely died this date, July 26th, in 1854 of Cholera and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Ms. Stokely was vacationing at Cape Island, NJ (now Cape May)and contracted Cholera. The doctor who wrote the death certificate believed Ms. Stokely caught the disease from prolonged exposure to the “Heat of the Sun.” Even for 1854 this was quackery. Mainstream medicine at the time believed the disease was caused by miasma or exposure to an unpleasant smell or vapor. Perhaps similar to the smell of a decaying corpse or rotting fruits or vegetables. It wasn’t until 1884-85 that science was able to identify the Cholera bacteria as the source of the deadly illness. The disease was commonly brought on by drinking water contaminated by the feces from a person who already had the Cholera bacteria. The bacteria could also come from raw or undercooked fish and seafood caught in waters polluted with sewerage. The crippling symptoms of Cholera came quickly, first diarrhea and vomiting, abdominal cramps, shock, then death.

Harriet Tubman worked as a cook in Cape May in 1852, earning money to help runaway bondsmen. She developed fugitive slave routes in Salem, Cumberland and Cape May counties, including obscure Indian trails. – See more at http://www.capemay.com/blog/2001/09/cape-mays-role-in-history-pathway-to-freedom/#sthash.97naePSS.dpuf.

Margaret Shorter, 55 years of age, died this date, July 24th in 1849 after suffering a stroke. Sadly, little else is known about Ms. Shorter. She lived on Cobb Street which is across the street from Bethel Burying Ground. It is very likely she lived at #3 Cobb Street and was a live-in domestic for the African American Brister/Parker family. For further reading on this family, I suggest going to http://www.archives.upenn.edu/people/1800s/brister_james.html.

Robert Howard, 63 years old, died this date, July 21st, in 1849 of Cholera and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. From the records of the 1847 African American Census, it appears that Mr. Howard lived with his spouse, several children and possibly his or her’s parents and/or grandparents. There was one female in the family over 100 years old. The Howard family lived in Acorn Alley (now Schell St.) which ran between 8th and 9th streets and Bainbridge and Fitzwater streets in south Philadelphia. He worked as a cook and Ms. Howard took in washing to add to their income. The Howards were neighbors of the Reverend John Boggs an AME minister of some prominence. Rev. Boggs died a little over a year before Mr. Howard.

Tragically the city was being ravished by Cholera in the summer of 1849. Mr. Howard was one of 196 individuals that died in the city and county of Philadelphia the same week as he did. Twenty-eight people a day were dying from the disease. (Public Ledger, 25 July 1849, p. 2.)

Eight-seven-year-old Sarah Bass Allen died this date, July 16th, in 1849 of “old age” and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. She was born enslaved in Virginia and in 1794 at approximately 20 years old is listed in The Philadelphia directory and register, 1794″ as living as a free person at 13 Shippen Street in the Southwark district of the county. Ms. Bass reported her occupation as “washerwoman.” She married the Reverend Richard Allen, founder of the AME Church, on August 12, 1801. The Allens had six children Richard L., James, John, Mary Ann, Peter and Sarah. (1)

Sarah Allen is revered in the AME Church as “Mother Allen” and “First Mother. She is hailed for her vigorous support of her husband and other AME ministers in their mission to spread the doctrine of the Church. She is also known for her courageous nursing service during the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1793. (2) In addition, she is reported to have been an active conductor on the Underground Railroad. (3)

It appears Sarah Allen was initially buried at Bethel Burying Ground instead of ground around Bethel Church because of ongoing construction. At some point, her remains were buried on church ground and in 1901 was placed next to her husband’s remains in a crypt in the basement of the church. (4)

(1) Aaron Goodwin, “The Richard Allen Family,” Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine, vol. 47 (2011), 215-47.

(2) J.M. Powell, Bring out Your Dead, p. 101.

(3) Jessie Carney Smith, Freedom Facts and Firsts, p. 237.

(4) Carol V. R. George, Segregated Sabbaths; Richard Allen and the emergence of independent Black churches 1760-1840

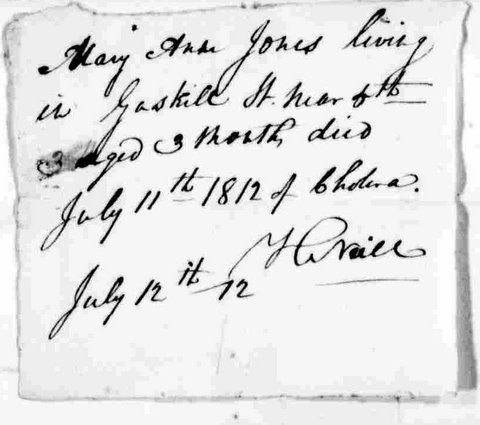

Three-year-old Mary Ann Jones died of Cholera on this date, July 12th, in 1812 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. I could not find any further information on her family, however, historian Gary Nash* had this observation about Gaskill Street.

“Gaskill Street, A narrow street running only three blocks from 2nd to 5th between Cedar and Lombard, had only one black household indicated in the 1793 yellow fever survey, only two listed in the 1795 directory, and only three recorded in the directory of 1811. But five years later 24 black families were spread along Gaskill, 22 of them in the block between third and fourth Street. . . . The 24 black families on Gaskill Street in 1816 lived in a neighborhood formed a nearly perfect cross-section of Philadelphia’s industrious middle and lower classes.”

Richard (aka Rich) approximately 50 years old, died this date, July 9th, in 1813 of Hydrothorax* and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. He was an enslaved Black man (“a Negro Slave”) imprisoned by John Stille, a wealthy Philadelphia merchant who was now deceased and so consequently Richard was now “belonging” to the Steele estate.

Between 1790 and 1800, the number of enslaved in Pennsylvania dropped from 3,737 to 1,706. Three years before Richard died (1810) there were 795 and by 1840, 64 bondsmen in the state. By 1850, there were none.* For further reading on the subject, I recommend Forging Freedom by Gary B. Nash.

*Fluid builds up in the chest cavity around the lungs and suffocates the victim. Causes can be from different diseases or heart or liver problems.

**http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/empowerment/18325/gradual_abolition_of_slavery_act/623285).

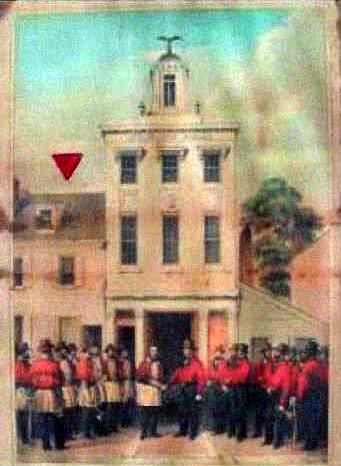

Ten-month-old Edward Braddock died this date July 1st, in 1848 of Bronchitis and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. His father, John, worked as a seaman at the nearby Delaware River docks for $20 a month. His spouse took in washing and ironing to supplement their income. They paid $5 a month for a room or shanty in the rear of 115 Queen Street only three blocks from Bethel Burying Ground.

Tragically the Braddocks lost another child five days later again to Bronchitis. William was only one-month-old. He was likely buried in the same grave as his brother.

The Braddock family lived next to the Weccacoe Fire Company. The red arrow points to the house that the family lived behind. Another neighbor was AME Bishop Morris Brown who lived at 154 Queen Street with his family.