Archives

All posts by Terry Buckalew

Missing are the Bethel Church records stating the price of interning a loved one at Bethel Burying Ground for a congregant or stranger (non-congregant). Hopefully, one day they will resurface. What we do have is the records of “The First Colored Wesley Methodist Church” that stood 90′ from Bethel Church (see below). Sometimes referred to as “Big Wesley” or “Brick Wesley,” it was established by “disaffected Bethelites” that broke away from Bethel in 1820. In addition to their house of worship that used the land around the church as a burying ground for their congregants and strangers. On November 11, 1830, the trustees decided to raise the prices of burials to $4 and $2 for adults and children of the congregation. And $8 and $4 for adult and child strangers. These charges are in addition to the price of a tombstone, coffin, a shrouder and bier or hearse, if necessary. This all in an era where the typical African American Philadelphians who labored for a living was making around $5 a week.

The cost of burying a body in the Potter’s Field – $0.

Jane Cummings, 33 years old, died this date, November 18th, in 1824 due to the “consequence of an abortion” and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground.

A Simple Human Right; The History Of Black Women And Abortion by Loretta J. Ross (On the Issue Magazine, Spring 1994). Available at

http://www.ontheissuesmagazine.com/1994spring/spring1994_Ross.php

Dorothy Brown, MD, the first black female surgeon in the U.S., was also the first American state legislator to attempt to legalize abortion. As a member of the Tennessee state legislature in 1967, she proposed a bill to that effect and her commitment to reproductive rights remained strong in the decades that followed. In a 1983 interview she cut to the heart of the conflict about abortion in the black community when she said black women “should dispense quickly the notion that abortion is genocide; genocide in this country dates back to 1619,” the year African slaves were first brought to America.

The tension between the resistance to externally imposed population control and the right of individual women to avoid involuntary motherhood marks the history of black women and reproductive rights in the U.S. It’s a fascinating story in its own right, but is also quite relevant to our current struggles.

For today, black reproductive rights activists often face a double challenge. They work to mobilize a black community that is still haunted by the idea of abortion as acquiescent genocide. And they must also work with white women activists, who may believe black women are too new to the struggle to be able to determine present day strategies and future direction. For example, a call last year by the National Black Women’s Health Project to launch a campaign to repeal the Hyde Amendment got only a small response from white activist groups. Reconstructing the impressive history of black women and abortion can help us all understand the underlying tensions that divide us and the deep commonalities that can help us work better together in the future.

Ancient Methods in America

Under slavery, African American women used contraceptives and abortionists to maintain some control over their bodies – sometimes as an act of political resistance, but more often as a statement of simple human rights. They defied overwhelming odds that devalued women as mere breeders, and also threatened their very survival through forced over-breeding.

African female slaves arrived in America with the knowledge of methods contraception and abortion as part of their historical heritage. Evidence of abortion-inducing herbs and methods have been discovered in ancient societies in Africa, China and the Middle East. Hatshepsut, the African queen and pharaoh who reigned in Egypt between 1500 and 179 B.C., invented a method of birth control. Ancient Islamic medical texts gave thirteen different prescriptions for vaginal suppositories that prevented conception after sex.

Plantation owners were distressed because their slaves seemed to be “possessed of a secret by which they destroy the foetus at an early age of gestation,” Dr. E.M. Pendleton complained in a medical essay in 1856.

Some of the methods used by slave women are quite alarming by today’s standards. They included drinking turpentine or liquid from boiled rusty nails, and taking quinine tablets. These concoctions brought about severe contractions which presumably induced abortions. Other women used strenuous and exhausting “exercise” or a combination of “tansy, rue, roots and seed of the cotton plant, pennyroyal, cedar berries and camphor,” according to Dr. John Morgan of Tennessee in 1860. Towards the end of the 19th century, alum water was used as a contraceptive in Southern rural communities where the midwife tradition was strongest.

Many of these methods were as dangerous to the woman as to the fetus, but apparently were effective enough to become part of folkloric wisdom for centuries in nearly every culture. The women were desperate, and therefore determined.

For African midwives, America proved to be a dark continent where knowledge was suppressed and servitude learned. A midwife named Molly, converted to Christianity, was made to repent the hundreds of abortions she had performed. “I was carried to the gates of hell,” she said, “and the devil pulled out a book…. My life as a midwife was shown to me and I have certainly felt sorry for all the things I did, after I was converted.” Women’s power was thus diminished through submission to the male-dominated black church, which was then the spiritual lifeline of most African Americans.

Sexual Respectability vs. Birth Control

After the Civil War, African American women deliberately increased their control over child spacing. “Not all women are intended for mothers,” was one of the points made in The Women’s Era, an African American women’s newspaper that was part of the first women’s movement of the late 19th century. This was revolutionary thinking indeed for an era that shamelessly promoted motherhood as the only respectable occupation for Victorian women.

With their bitter legacy of rape and forced breeding at the hands of white plantation owners, black women had a special view of the costs of involuntary motherhood and many found the early feminists’ concept of voluntary motherhood attractive. They warmed to the feminist belief that smaller family size aided upward economic mobility.

But black women also faced a social dilemma: contraception and abortion was considered morally repugnant – the province only of prostitutes and prurient women – in the Victorian era. At this time, black women were striving to attain “sexual respectability” and to overcome vicious stereotypes. Black women had been perceived by white America as the ”whores and mules” of society, doing the dirtiest work, caring for white children and families, but available to white men for sex, without regard for laws or morals, wrote Zora Neale Hurston in 1937. And so black women procured contraceptives and abortions privately and quietly.

Long after midwifery was suppressed in other parts of the country, midwives provided the majority of health care to black Southern women well into the 1960s. They were part of the informal networks through which black women shared birth control and abortion information. These efforts were applauded by noted black intellectuals like J. A. Rogers, who wrote in 1925 that he gave “the Negro woman credit if she endeavors to be something other than a mere breeding machine.”

By the early 1900s, black women had made significant gains, with most having fewer children and marrying at a later age than their grandmothers. At the turn of the century, W.E.B. Du Bois noted that half of all educated married black women had no children. Even more revealing: one-fourth of all black women, the majority still rural and uneducated, had no children at all.

At the same time, African American women also reduced infant mortality. Between 1915 and 1920, black infant mortality dropped from 181 to 102 per 1,000 births for states registering more than 2,000 black births. Throughout history, no country (or ethnic group within a country) has ever lowered its population growth rate without first lowering its infant mortality rate, according to Betsy Hartmann of the Population Program at Hampshire College. This important relationship should inform today’s perspectives on population growth and reduction.

Birth Control vs. Eugenics

Margaret Sanger, in her drive to establish birth control clinics throughout 20th-century America, touched a responsive chord in African American women, many of whom were middle-class like most of their white counterparts. In 1918, the Women’s Political Association of Harlem announced a scheduled lecture on birth control. Alice Dunbar Nelson endorsed birth control in an article in 1927. The National Urban League requested of the Birth Control Federation of America (forerunner to Planned Parenthood) that a family planning clinic be opened in the Columbus Hill section of the Bronx. Later still, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., spoke at public meetings sponsored by women’s groups in support of family planning. The NAACP openly supported reproductive rights. The dominant view of the times was that African Americans needed to control family size in order to integrate, through education and jobs, into the American mainstream.

During the same period, European immigrants and their descendants were being encouraged to breed. Rapid population growth helped overrun the Native Americans, settle the west, and fulfill a mythical “Manifest Destiny.” Religious and political leaders denounced birth control as part of a Victorian backlash against the growing sexual freedom of women. Comstock laws prohibiting the distribution of birth control information were first passed in 1873.

Alongside the birth control movement, the pseudo-science of eugenics, which aimed to limit the reproduction of “undesirables,” grew into a movement in America and Britain. It was part of the white American frenzy against the African American progress during Reconstruction. By the 1920s, more than five million whites openly belonged to the Ku Klux Klan, including U.S. Congressmen. President Theodore Roosevelt made dire predictions about “race suicide” if America continued to tolerate rising birth rates of black Americans and “non-Yankee” immigration. In fact, the birth rate of black Americans was slower than that of whites at the time, but it suited the purposes of the racial alarmists to distort the facts. Blacks, Catholics and others were singled out for planned population reduction through both government and privately financed means.

In 1939, a Negro Project designed by the Birth Control Federation hired black ministers and nurses to travel the South recruiting black doctors. Designed with blatantly racist intent, the project equated southern rural poverty not ¥with racism or with Jim Crow, but with the black birth rate, which was only slightly higher than whites. “The mass of Negroes,” read the project report, “still breed carelessly and disastrously, with the result that the increase among Negroes…is from that portion of the population least intelligent and fit.”

Early Black Anti-Abortionists

While W.E.B. Du Bois, the NAACP, and the “black bourgeoisie” continued to support reproductive choices, not all African Americans followed suit. A strong black nationalist movement, led by Marcus Garvey, a “Back to Africa” proponent from jamaica, opposed fertility control for black women. They argued that blacks must, in fact, increase their population size to succeed in erasing the remnants of slavery and regaining the heritage and power of ancient Africa. Women’s wombs became weapons in the war against racism.

Garvey received considerable support from the Catholic Church and formed alliances with white conservatives and extremists who feared the availability of birth control for white women.

The black nationalist movement monitored the growing relationship between the eugenics movement and Margaret Sanger who, in her zeal to promote the birth control movement, allowed it to fall under the onus of racism perceived in the eugenics movement. In The Pivot of Civilization, published in 1922, she urged applying stock breeding techniques to society in order to avoid giving aid to “good for nothings at the expense of the good.” This linkage of two very different concepts of birth control and population control created enduring suspicions in the minds of African Americans.

Those involved in the organized black women’s movement sought to point out the differences. In black newspaper articles and editorials of the 1930s and 1940s, they protested against the arrests of doctors who performed illegal abortions and laws banning birth control. They pointed out the vast difference between an individual woman’s right to control her body and eugenic policies, including the forced sterilization of black women, that attempted to manipulate entire populations. Senate committee testimony revealed that at least 2,000 involuntary sterilizations had been performed on poor black women without their knowledge and consent with Office of Economic Opportunity funds in the U.S. during the 1972-1973 fiscal year. According to Dr. Robert S. Mendelsohn in his book Male Practice: How Doctors Manipulate Women sterilization abuse remains a problem to this day.

Population time-bomb theories in the 1950s provided new rationales supporting population control for black women. Brochures published by such population groups as the Draper Fund and the Population Council depicted black and brown faces swarming over the tiny earth. Family planning, it was argued, would support U.S. efforts to control and govern world affairs in the post-war years.

From the 1950s until the Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion in 1973, black women obtained abortion services from underground providers. Many white women came to black neighborhoods to obtain abortions. Middle-class women could sometimes persuade doctors to perform a discreet abortion or provide a referral, but poor women went to “the lady down the street” – either a midwife or partially trained medical worker. Abortions by these illegal providers were expensive, costing between $50 and $75 at a time when black women earned less than $10 a day. Rich women who went to doctors paid as much as $500. Afraid of the legal consequences of having obtained an illegal abortion, women resorted to hospitals only if there were complications. Consequently, the rate of septic abortions reported to hospitals was low.

Black doctors and midwives who performed abortions were prosecuted far more often than their white counterparts, although Dr. Edgar Keemer, a black physician in Detroit, performed abortions outside the law for more than 30 years before his arrest in 1956.

Birth Control as Poverty Control

By the late 1960s, many people viewed family planning as synonymous with civil rights for black women. Through the Office of Economic Opportunity, Congress waged a war on poverty that focused on establishing family planning clinics in black neighborhoods. Of particular concern were those communities in which black political power was developing. Many Americans feared the black inner cities and sought to curb black population growth there. Stereotypes about a “welfare class” arose, partially as rhetorical attacks from far right opponents of civil rights.

It is important to note that the 1965 Voting Rights Act was passed the same year family planning was introduced on a national scale. Medicaid, established in the 1960s to pay for medical costs for the poor, eventually included family planning along with abortion services in those states with liberal abortion laws. Black women had their greatest access to legal abortion services during this time, until passage of the Hyde Amendment in 1976 which prohibited use of federal funds for abortion. Noted black family planning advocates like Joan Smith of Louisiana and Dr. Joycelyn Elders, the U.S. Surgeon General, began their careers during this period. Outside of the medical system, alternative abortion providers such as the Jane Collective in Chicago were developed not only to serve black women, but to involve them as members and practitioners.

The male-dominated black nationalist movement of the 1970s, in the spirit of Marcus Garvey, wanted to wage the race war with rhetoric and wombs. Several birth control clinics in black neighborhoods were invaded by Black Muslims associated with the Nation of Islam, who published cartoons in Muhammed Speaks that depicted bottles of birth control pills on the graves of unborn black infants. William “Bouie” Haden, leader of the militant United Movement for Progress in Pittsburgh, threatened to firebomb a Pittsburgh clinic. The Black Panther Party was the only nationalist movement to support free abortions and contraceptives on demand, although not without considerable controversy in its ranks. By 1969, a distinct black feminist consciousness about abortion had emerged. “Black women have the right and the responsibility to determine when it is in the interest of the struggle to have children or not to have them and this right must not be relinquished to any,” the Black Women’s Liberation Committee of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) wrote in 1969.

Black feminists argued that birth control and abortions were, in themselves, revolutionary – and that African American liberation in any sense could not be won without that basic right of bodily self-determination. “I’ve been made aware of the national call to Sisters to abandon birth control…to picket family planning centers and abortion referral groups and to raise revolutionaries. What plans do you have for the care of me and my child?” wrote Toni Cade (Bambara) in 1970.

Today, there remains opposition to abortion, mainly in the growing right wing, but also on the left in the black community. Black conservatives, insisting that sexual restraint and self-help are the answer, ally themselves with the right to-life movement. Opposition to abortion also comes from some groups who identify with the teachings of Martin Luther King, Jr. They argue that if Dr. King were alive he would probably oppose abortion, and call for a “seamless garment of nonviolent belief,” opposing war, racism, the death penalty, and abortion.

Nonetheless, support for legal abortion is strong among black women – 83 percent of African Americans support abortion and birth control, according to a 1991 poll by the National Council of Negro Women and Communications Consortium Media Center.

Enabling poor women, too, to control their own bodies is a major concern of black activists. As W.E.B. Du Bois wrote seventy years ago: “We are not interested in the quantity of our race. We are interested in the quality.”

Loretta J. Ross is program director at the Center for Democratic Renewal, Washington, DC. She is working on a book on the history of black women and abortion.

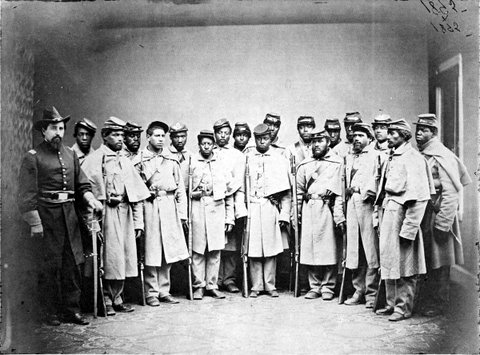

In my years of research on Bethel Burying Ground, in addition to the dead, I have studied the people and the neighborhoods surrounding the small, but busy cemetery. I have also studied the Black cultural rituals of the era connected to Methodist funerals and have always come away with a nagging question about the safety of the funeral processions. Here you have a large group of Black men and women mourners walking through the violently dangerous streets of Anglo-Irish neighborhoods following the funeral bier all the way to Queen Street with the funeral march passing saloons on every corner and the clubhouses of the racist volunteer firemen klans. Yet there ae no newspaper accounts of any confrontations.

However, there is one piece of interesting reporting by William Carl Bolivar, a well-respected African-American historian, and journalist of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As a columnist for the Philadelphia Tribune, he wrote in his column “Pencil Pusher Points” on December 21, 1912, the following:

“Doctor” J.J. G. Bias was a dispenser of homemade medicines, a cupper and bleeder, and did a thriving business on the east side of Sixth below Lombard streets. He united to that, pulpit skills in the A.M.E. Connection. “Dr.” Bias was public spirited and led in all the early fights against the slave inequity.In fact, he led a large force, known as “Bias’ mob,” against the attacks of the thugs and pro-slavery firemen nearly seventy-years ago. Philadelphia has always breathed in an atmosphere where all sorts of men with peculiarities were a part and had an influence, as a role for much good, even if the processes were unconventional.

Could there have been a Black defense organization who, as one of their duties, protected funeral processions? In following posts, I will explore in more details the life and career of Dr. Bias and his wife, Eliza Ann Bias, a courageous suffragette and civil rights organizer.

The following are those that died on November 10th and were buried at Bethel Burying Ground.

Beck, Unspecified: 0; us; stillborn; 10 November 1829; father, John Beck.

Bostick, Ann: 2y; f; Convulsions; 10 November 1824.

Gibbs, Henrietta: 38y; f; “died in child bed”*; 10 November 1821.

Lee, Margaret Fischer: 18y; f; Meningitis; 10 November 1847.

Wilson, Benjamin: 7m; m; Scrofula**; 10 November 1825; resided, Cherry Street near 7th St.

Winn, Richard: 14y; m; Scrofula**; 10 November 1822.

*died during childbirth

** a disease with glandular swellings, probably a form of tuberculosis

The six-month-old son of Thomas and Francis Wilkins died this date, November 5th, in 1848 of Bronchitis and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Unfortunately, I have not been able to locate any additional information on the Wilkins family. What is interesting from a historical standpoint is that the family lived in the Port Richmond district in the County of Philadelphia which was several miles away from Bethel Burying Ground. There was a closer AME church with a graveyard (Union AME) in the far eastern part of the Fairmount district. Perhaps there was another family member (another child?) buried at BBG and the parents wanted to keep them together. Another possibility is that a Bethel Church beneficial society offered burial assistance.

More than one-third of the 2,490 identified so far buried at Bethel Burying Ground are infants 2 years old and younger. The lack of a nutritional diet accounts for the majority of these deaths. Starvation was a very real problem for the desperately poor families. More often it was a lack of protein (meat) that was expensive and out of reach of many families. Also, the inability of pregnant women to obtain adequate nutrition contributed to the birth of babies with weakened immune systems that made them more susceptible to a long list of deadly diseases.

For an excellent overview of the subject see African Americans in Pennsylvania: Shifting Historical Perspectives, pages 335, 337, 343-44, 353, 354-55.

All deaths are tragic. Some more so than others. Twenty-one-year-old Elizabeth Cole died this date, October 21th, in 1848 of Tuberculosis and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Ms. Cole appears to have been the female head of her family with her mother deceased or away and her father a seaman and also absent from home for long spells. Census records show that Ms. Cole cared for 3 siblings while occupied as a day worker. Two of the smaller children were attending the Shiloh Infant School. The Cole family lived at 41 Currant Alley where they rented a room for $28 a year. The Cole family attended religious services, presumably Bethel Church (now Mother Bethel).

Currant Alley ran from Walnut Street to Spruce Street between 10th and 11th streets in the Ward 7 of the City.

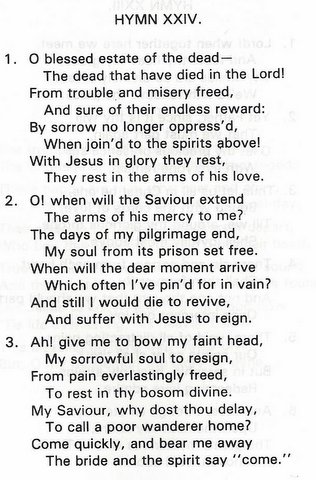

Burials at Bethel Burying Ground were often, but not always preceded by a memorial service at Bethel Church (now Mother Bethel). The historical record contains the details of such a service in 1805 in which the following hymns were sung –

-Rejoice for a brother disceased [sic]

-Hark from the tombs

-My God my heart with Love inflame (1)

On the way to the gravesite, the procession sang “A solemn March we make.” On returning from the grave, the mourners would also sing. A popular hymn for this occasion was from the hymnal that Richard Allen published in 1801. It was “O blessed estate of the dead.”

Long lines of mourners in procession from 6th and Lombard Streets to 5th and Queen Streets singing to the heavens – what a beautiful scene that must have been!

(1) American Methodist Worship, Karen B. Westerfield Tucker, 207-08.

Three-year-old Francis Tate died this date, October 16th, in 1852 from a fever of unknown origin. He was the son of Arthur and Margareta Tate who lived with their four other children in a room located in a 3-story brick building in the 900 block of Lombard Street near Bethel Church (now Mother Bethel). Their rent was $1.75 a month. Arthur was employed as a porter and Margareta was a day worker according to the 1847 African American Census. It appears from the Census that Francis attended the nearby Lombard Infant School. One of the parents was formerly enslaved and gained their freedom through manumission.