Twenty-eight-year-old William Hopkins died this date, December 6th, in 1848 from lack of “medical attendance” according to the City Coroner. Little else can be found about Mr. Hopkins at this time. He may have been the person that advertised in the February 1848 newspapers an “Oyster cellar” for sale at 154 South 6th Street. Maybe not. I believe historian Michael A. Ross said it best about this type of research. “When writing micro-history, it often seems as if your subjects have gone down the hall, around the corner, and out the door.” At this point, frustratingly, Mr. Hopkins is around the corner.

On This date

Five-year-old Charlot Fitzpearl died this date, November 26th, in the year 180 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Her actual name was probably Charlotte Fitzgerald. There was no doctor in attendance when she died of “Decay.” This term describes the individual’s condition and is no assistance in ascertaining the exact cause of death. The child’s death could have been from dozens of sources including lead poisoning, Sickle Cell Disease, lack of nutrition, trauma, a congenital disease or the many serious respiratory diseases that were epidemic in the community.

Five-year-old Charlot Fitzpearl died this date, November 26th, in the year 180 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. Her actual name was probably Charlotte Fitzgerald. There was no doctor in attendance when she died of “Decay.” This term describes the individual’s condition and is no assistance in ascertaining the exact cause of death. The child’s death could have been from dozens of sources including lead poisoning, Sickle Cell Disease, lack of nutrition, trauma, a congenital disease or the many serious respiratory diseases that were epidemic in the community.

On this date, November 23rd, in 1843, Diana Jackson died of “old age” and is buried at Bethel Burying Ground. She had reached the age of 101 years. Of those interred, whose death certificates have survived, there are 19 individuals buried at the Queen Street cemetery between the ages of 90 and 103 years of age. This is astounding considering their life expediency was in the late 20s to early 30s! There is no reliable data at this point to determine with specificity the life expectancies of the Black men and women in 19th century Philadelphia. However, the First African Baptist Church Cemetery (FABC), located at 8th and Vine Streets in Philadelphia, was excavated and the remains examined during the 1980s. There is a 21-year overlap in usage between this cemetery and the Bethel Burying Ground – circa 1822 to 1843. There were 135 skeletons recovered and studied from the Vine Street graveyard. It was determined that the life expectancy of these individuals was 26.59 years according to anthropologist Dr. Lesley M. Rankin-Hill, author of A Biohistory of 19th-Century Afro-Americans: The Burial Remains of a Philadelphia Cemetery. This small book is a wealth of information on the 19th century Philadelphia African American community and the medical and socioeconomic struggles they endured. A must read for anyone who is serious about understanding the history of Black Philadelphians.

In addition, Rebecca Yamin’s Digging in the City of Brotherly Love: Stories from Philadelphia Archeology offers vital insights into the FABC excavation and the community outreach of the archeologists handling such a culturally sensitive project. I used their template for community outreach in my initial contact with relevant “shareholders” concerning the future of the Bethel Burying Ground. ”The Swift Progress of Population”: A Documentary and Bibliographic Study of Philadelphia’s Growth, 1642-1859 is not for the casual reader. It is a valuable guide to the demographics of early Philadelphia. I feel that every time I open this book I discover something new and remarkable. Dr. Susan E. Klepp, the book’s author, is the former Professor of Colonial America and American Women’s History at Temple University.

Mr. William Winters, 40 years old, died this date, November 20th, in 1824 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground. He was a labourer who lived at 269 Catherine Street just two blocks from the burial ground. His cause of death was Typhus Fever. Some may confuse Typhus and Typhoid. I know I initially did. The name Typhoid means “resembling typhus” and comes from the symptoms common to Typhoid and Typhus. Despite this similarity of their names, Typhoid and Typhus are distinct diseases and are caused by different species of bacteria.

Typhus is caused by the rickettsiae bacteria and transmitted by flea, mite and tick bites. When these parasites bite a victim, they leave the rickettsaie bacteria behind. Scratching the bite opens the skin to the bacteria, allowing them to enter the bloodstream. Within the bloodstream, the bacteria grow and replicate. A rash covers the entire body of the victim accompanied by a high fever. The individual will suffer petechaie, which is bleeding into and through the skin. Delirium, stupor, hypotension, and shock occurs followed by death.

Typhoid fever is a totally different bacterial disease transmitted by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person, which contain the bacterium Salmonella enterica. This disease has been a deadly human disease for thousands of years, flourishing in conditions of poor sanitation, crowding, and poverty. After becoming infected the victim, develops a high fever and becomes exhausted and emaciated due to constant diarrhea and the perforation of the intestines. The patient develops septicemia, slips into a coma and dies.

Although antibiotics have markedly reduced the frequency of these diseases in the developed world, it remains endemic in developing countries.

On November 16, 1842, Mary Ann White died at 48 years of age of Chronic Peritonitis. This very painful condition was incurable before the advent of antibiotics. One common manner for a woman to die of this condition was a botched abortion. Some deaths are recorded as caused by an abortion, but more often they are labeled as “Peritonitis.” For more on the subject please see – When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States, by Leslie J. Reagan.

Ms. White lived in Barley Street, really an alley, in the Queen Village neighborhood of the city. Barley is now Waverly Street. Below is a photo of this ally as it currently looks.

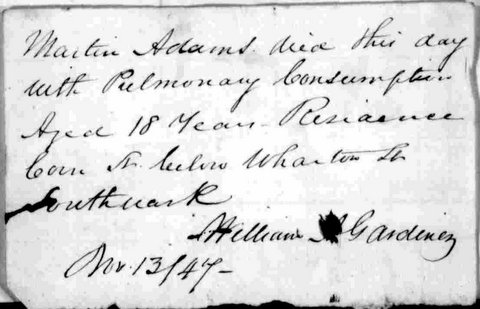

Eighteen-year-old Martin Adams died this date, November 13th, in 1847. The cause of death was Consumption. We know the disease today as Tuberculosis. Martin lived on Corn Street (now American Street) below Wharton Street. His home was near 2nd and Christians Street in the Southwark neighborhood now known to some as Queen Village.

Tuberculosis was the leading cause of death (17.6%) for those buried at the Bethel Burying Ground.

Two-year-old Alfred Matlack died this date, November 12th, in 1848. His cause of death was “Catarrh,” which simply means fever accompanied by mucous secretions. The cause of the fever could have been Pneumonia, Influenza or even Typhus. Tragically, the Matlack family would lose another son, 8-month old Thomas to Pneumonia on May 12, 1850.

Alfred’s father, James, was a hod carrier which was a laborer employed in carrying bricks to bricklayers or stones and supplies to stonemasons. Alfred’s mother was a wash woman who took in laundry.

The Matlack family lived in an alley street called Bird’s Court, which was located between Locust and Spruce Streets and 10th and 11th Streets in the Washington Square neighborhood of Philadelphia. Their home would have been very near Pennsylvania Hospital.

When initially established in 1810 the Bethel Burying Ground was a rural cemetery. Maps of the era show the land as a pasture used by local farmers for grazing cattle and sheep. There were no paved or graded roads, just dirt paths. However, this “suburb” of Philadelphia quickly grew, eventually placing the small cemetery literally in the backyards of tenements on Catherine Street and row homes on Queen and Weccacoe Streets.

And unfortunately in time, like many other graveyards in Philadelphia. BBG fell into poor condition and the trustees of Bethel Church were issued warnings several times in its existence (1810-1889) by the Philadelphia Board of Health to repair and clean up the nuisances asserted by the neighbors that bordered the burial ground.

On November 10, 1847 the Philadelphia Board of Health ruled that BBG was a public nuisance following complaints by neighbors and an inspection by Board members. They issued the an order to the Church’s trustees: “You are hereby notified, that in all future interments made therein each body shall be deposited in the grave six feet in depth, and filled up with earth to a level with the proper surface of the ground; and that nobody shall be kept upon any part of the said grounds, or in any place appertinent and thereto, for a longer period than two hours previous to it being interred as above directed.” Philadelphia Board of Health Minutes for November 10, 1847.

It appears from the archeological record that the trustees answer to the problems was to build a two-foot high brick wall around the graveyard and backfill it with soil. This not only solved the problem of human remains being exposed, but allowed the trustees to bury more bodies in a very crowded area.

“The fact that the cemetery wall is not anchored into the underlying subsoil—but rather sits on top of the buried historic ground surface—and is bounded on either side by visually distinct fill deposits—strongly suggests that this enclosure was originally constructed at or about the time that fill soils were deposited both inside the cemetery grounds and in the adjacent backyards, in order to fill up low-lying areas and level the ground surface. Based on findings from the Phase IA investigation, it was previously thought that this fill was perhaps brought in after the cemetery was closed—possibly during the tenure of Barnabas H. Bartol (1869–1873) or in conjunction with the city’s first improvements to Weccacoe Square in the early 1890s. However, information from the Phase IB study now suggests that this fill material was probably put down at a time relatively late in the period that Mother Bethel was still actively using the burial ground.” (Page 4.1 – Phase IB Archaeological Investigations of the Mother Bethel Burying Ground, 1810 – Circa 1864ER No. 2013-1516-101-A).

Photo of the north retaining wall of the BBG with the headstone of Amelia Brown protruding from the soil. This photo is in the archeological report page 3.17.

“In the 18th and early 19th-century churchyards became increasingly crowded. They became filled and their management became a problem. The limited financial security of a congregation often led to a movement of places of worship and abandonment of burial grounds, which were then redeveloped, and several in Philadelphia have been examined. (Mortuary Monuments and Burial Grounds of the Historic Period, H.C. Mytum, p. 45.)

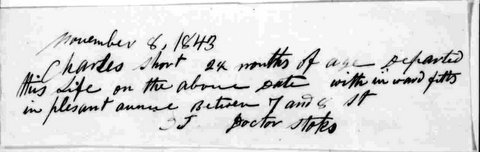

Two-year-old Charles Short “departed this life”, November 8th, in the year 1843. He resided with his family in the Northern Liberties neighborhood of the city. His home would have been near present-day 7th Street and Fairmount Avenue. The cause of Charles death was reportedly from “Inward Fits.” Also known at the time as “Spasmodic Croup.” The majority of the child inflicted with this disease did not die. However, when it did prove to be fatal it was from the child dying from suffocation due to the severity of the “fit” or spasm of the muscles in the throat. It is often seen as an early symptom of Hydrocephalus.

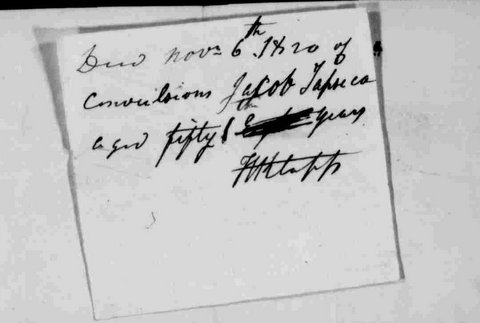

Reverend Jacob Tapsico died this date, November 6th, in 1820 and was buried at Bethel Burying Ground

The Reverend Jacob Tapsico died this date, November 6th, in 1820 of “convulsions.” He was 51 years of age. A soap maker, he eventually became the second ordained Elder of the Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church and the second pastor of Mother Bethel. His home was on in the 700 block of Shippen Street (now Bainbridge Street) in the Bella Vista neighborhood of the city. For more information on Rev. Tapsico, please read Freedom’s Prophet by Richard S. Newman (p. 168).

The Reverend Jacob Tapsico died this date, November 6th, in 1820 of “convulsions.” He was 51 years of age. A soap maker, he eventually became the second ordained Elder of the Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church and the second pastor of Mother Bethel. His home was on in the 700 block of Shippen Street (now Bainbridge Street) in the Bella Vista neighborhood of the city. For more information on Rev. Tapsico, please read Freedom’s Prophet by Richard S. Newman (p. 168).